My 1989 Sonic Youth Feature

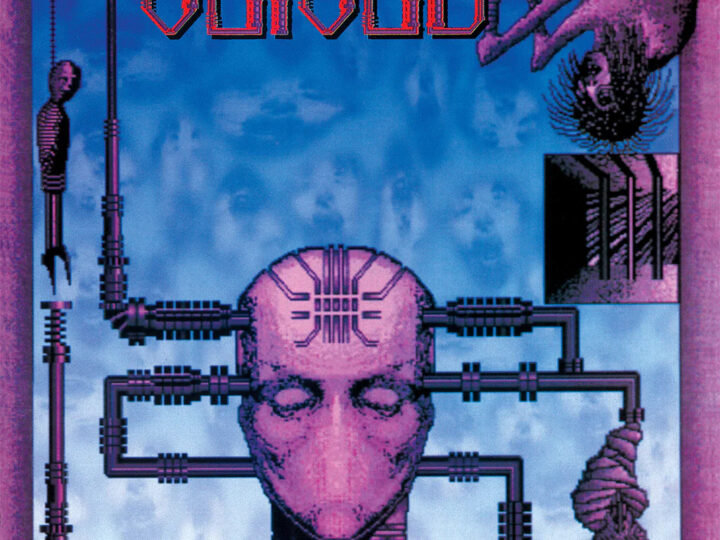

Spin magazine recently posted a Sonic Youth release Sister. The album is rife with images and ideas from Dick’s later books, most of which deal with his VALIS experience. Dick is thanked on the lyric page. The insert contains sigils used in Haitian vodun (voodoo) rituals, and a strange drawing Dick made, a hybrid of the Christian fish sign, the eye of Shiva, and the double-helix of DNA.

***

It’s 1981 and Philip K. Dick published Valis. In it, he asserts that VALIS crossbands with humans. “As living information, the plasmate travels up the optic nerve to the pineal body. It uses the human brain as a female host in which to replicate itself in an active form.” The divine virus is camouflaged, and doesn’t obviously alter the humans that it enters into symbiosis with. VALIS replicates itself “not through information or in information—but as information.”

***

It’s 1988, and one week after Blast First/Enigma Capitol disseminates Daydream Nation worldwide, a virus program infects Arpanet and Milnet, huge computer networks that service research and data management for America’s military-industrial complex. The virus steals passwords and disguises itself as a legitimate user. The program spreads throughout networks around the globe, replicating its information up to hundreds of times in each machine it reaches.

***

It’s 1982, and in March, the same month that Lester Bangs dies, Philip K. Dick succumbs to a massive heart attack.

***

It’s 1982, and Sonic Youth release their first record. I would say that this is only the beginning of the story, but that’s a misinterpretation of the facts, because nothing as recognizable as a story ever emerges. There are just fragments of some grand cabal, after-images, bits of torn messages, patches of infection, arrows pointing in a thousand directions: genetic engineering, Walt Disney, the Illuminati, Madonna, the dog-star Sirius, compact discs, Thomas Pynchon, guitar rock, video games, LSD. But it’s seldom more than a shredded map, and never a narrative with polite beginnings and endings. Maybe the thing itself is just some all-too human conspiratorial network that supports multi-national capital, a technological system of power and information control that most pop culture is designed to obscure. Or maybe it’s, well, something else, some sentient force outside conventional versions of reality, but no less real (“there’s something moving over there, like nothing I’ve ever seen”). But whatever the thing is, once you’ve glimpsed it, you start making conceptual leaps you probably shouldn’t be fucking with (“we make up what we can’t hear”). Once you realize that, like Satan, its greatest trick is to make you think it doesn’t exist, you’re screwed.

The viral network of information is the social paradigm of the ’80s, one that has a horrifying downside. AIDS makes viral metaphors dangerous and yet, all the more inevitable. It should be mentioned, re the above chronology, that AIDS first hit the TV networks in 1982, and was initially associated with Haitian immigrants. But conspiracies breed counter-conspiracies and a virus is not always malignant; genetics engineers use viruses to splice helpful information into the cells of people with congenital defects. AIDS and VALIS are opposing forces, one too real and one not quite real enough, under the same form (“hey—hypostatic information”).

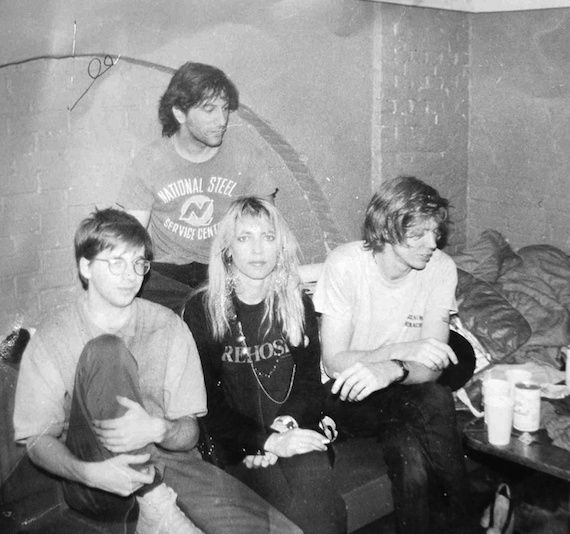

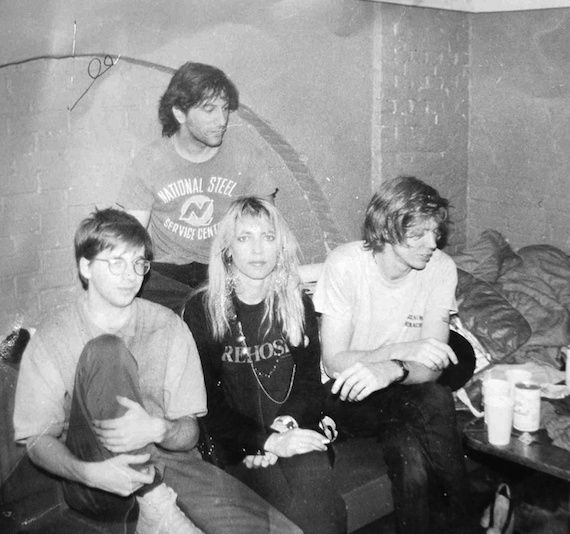

It’s a week before Halloween, and I’m with Sonic Youth in the Blast First! record office in SoHo. They’re acting about the way I’d expected. Thurston Moore, a blond beanpole, is campy and cocky and the most talkative. Lee Renaldo, Sonic Youth’s other vox/guitarist, looks like a pizza slinger with pupils the size of oranges, and he cuts through the bull a bit more than Thurston. Bassist Kim Gordon comes off sweet, friendly and mildly shy, a bit odd given her convincing Boho witch get-up and a stage presence that burns with sexuality once removed from ritual. Steve Shelley, who was raised as a child by mall-rats, seems tired, and doesn’t talk much.

The conversation’s okay rock-talk, covering: the history of Blast First! (named after a Futurist manifesto), some TV documentary about them on a “middle-class arty channel” in England, dissonance (“It’s more like sibling rivalry”), open tuning (“We’re not into the math of it”), why Daydream Nation sounds so fucking awesome (“It was a great studio”), why both the jams and the riffs are their best on record (“We played the songs live a lot before we recorded them. We never did that before”).

Interesting enough, but it’s more fun watching Thurston go off on bugs: “We’re into, like, bug things. Dinosaur’s record’s called Bug. Das Damen’s new single is called ‘Bug.’ The U-Men just put out an album called Step on a Bug.“

“And the Rapeman EP was called Bud,” Kim laughs.

“They really missed the boat,” Lee says. “Wrong letter.”

Steve is asleep.

“It’s not like hip hop,” Thurston explains, “like, ‘You’re bugging me.’ It’s like actual bugs.” Someone passes out Xerox copies of various insects, while Renaldo goes on about “arachnid rock.” I can’t help thinking of PKD’s 1977 A Scanner Darkly, whose only purpose in life is to eradicate the millions of bugs that he (falsely) perceives are infesting his apartment, his body, and his dog. So I bring up PKD, and the bugs disappear.

Sometimes you see the symptoms everywhere, crystalline visions that jam the air with meaning, like the multinational logos that loom over Times Square. It’s a lovable rush: your neurons become sentient fingers of a monstrous mutant network that sucks up every sign in its sublime reach (“hey—gold connection”). But it’s getting harder and harder to reach that state. You realize that your incapacity to deal is due to the greater and greater numbers of increasingly minute bits of data they keep slamming into you “scattered pages and shattered lights”). Your brain has already been reprogrammed into a multi-channeled hunk or perceptual technology that manages information and images, but your capacity to integrate the shit is beginning to fry (“gotta change my mind before it burns out”). The signs become fragments of signs, then just fragments, meaningless bits of junk in all their nauseous, stupid difference, and faith is just another boring psychic disorder (“her light eyes were dancing/she is insane/her brother says she’s just a bitch with a golden chain”).

So you watch TV, looking for any kind of sign (“I’m keeping my commission to faith’s transmission”). You’re on the Viral network and Paranoia and Schizophrenia are the only channels you pick up. But you can’t stay tuned to either one—you keep getting this strange interference, this distorted but alluring noise (“looking for a ride to a secret location”). You realize you’re picking up the live signal of a club down the street a slick slam-hole called the Postmodern Sensorium. You pull on your lizard boots, go down, check it out, and start dancing the latest dance: the cyberpunk stomp. Sonic Youth’s playing, and they’re clearly one of the hottest Sensorium dance-bands. As one percept-hacker tells you, “They’re real rock dog-stars.” No one can match their mutant post-sub-hyper-meta-generic thrash, and you learn that denizens deal their bootlegs like drugs, digital cartridges in small multi-colored packages with hundreds of names: Conspiracy Camp, Lethal Bubblegum, The Dissonant Riff, Divine Trash, Zebra.

Ooops.

You’re hooked.

***

“Phillip K. Dick understood and wrote about the schizophrenic experience better than anybody,” Thurston explains. “He’s definitely important on Sister. The lyrics to ‘Schizophrenia’ and ‘Stereo Sanctity’ were really taken from, like, Radio Free Albemuth (an early version of Valis). ‘I can’t get laid because everybody’s dead’ is right out of Valis.“

“He’s like a modern philosopher,” Kim says. “His books can be depressing, but I feel very centered whenever I read him.”

“He was very well-read,” Thurston points out, “but he writes in common speech, not like an academic. Dick was really compulsive. He’d change his mind all the time. I suppose he turned a lot of people off because he’d hop on any religious thing that came his way. Schizophrenia is just another word for cosmology.”

Or vice versa. When Dick wrote in Valis that “the symbols of the divine show up in our world initially at the trash stratum,” he was anticipating Sonic Youth’s lyrics, which mix in religious and occult imagery with their scuzzy skanking for pop and violence. The stuff is powerful enough to set off Dick’s kind of spiritual paranoia. One nutso Kim remembers “was just really strange. He wrote saying things like he couldn’t believe it when he heard Sister. He said ,’How could you make this record, ’cause I was hearing these songs in my head. You’re existing in my head.’ He sent lots of weird letters and books.” Kim says she can’t remember what books he sent.

I call them on their voodoo-Catholic acid dreams, but they dodge. “Well, I’m not religious,” Kim explains (“let’s go walking on the water/now you think I’m Satan’s daughter”). “Thurston was raised a Catholic, but it’s just something that fascinates me” (“no need to be scared/let’s talk to the dead”). Thurston breaks in: “It’s not really about religion. When I hear religion, I think of organized religion. I mean, the most separatist thing in our music is the lyrics. The person who sings usually writes the lyrics.”

I’m about to ask them why, if their lyrics are so separatist, they have such a similar feel, but Kim anticipates the question and says, “We all share the books we read.”

Thurston jumps in. “We share the knowledge behind them, but as far as espousing anything…” We talk about this shared information for a while: PKD, the Society’s newsletter, David Cronenberg’s “sex-as-virus metaphor” and his unfinanced Dick screenplay, and cyberpunks like William Gibson, Lucious Shepard, Bruce Sterling Michael Swanwick, John Shirley. Thurston’s disappointed when I tell him that Gibson is 40. “Well, that blows my theory that we’re contemporaries.”

***

Some more linkages are attempted, and then Kim comes out with the peak oddity of the day, crystallizing the Zeitgeist and shattering it at the same time: “Sometimes it’s amazing that anything happens. Like when you’re in a plane and you realize that there’s 300 people with you, and there’s all this baggage. It doesn’t seem very aerodynamic. It feels like you’re on a boat, and it’s flying. It’s just amazing and at the same time it feels so old-fashioned. It doesn’t parallel the level of communication most of us operate on, like with fax machines. It seems almost archaic.”

Pop theorists have noted that hip hop is the most innovative and visceral technological culture around. Nicholas Sansano, who helped engineer Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, offered his services to Sonic Youth and co-produced It Takes a Daydream Nation to Put Up With Us. Though on a different plane, Sonic youth share the same sublime matrix as hip hop: dense, tuff, hip to the harsh creole of machine language. The Youth bring the (white) noise to the urban stratosphere (“I’m just walking around/the city is a wonder town”).

True, the Youth have stepped in their share of East Village art-shit: They wank in loads of different tunings, stick forks into their guitars, use tape-loops and digital delays on live guitars, and employ dissonant structures and hyperharmonic overtones. But they still resonate more with BÖC thant Branca, ’cause they play viral variations of the same rock’n’roll guitar. They know the alchemy of noise that propelled the greatest of guitar bands: the search for the philosopher’s rock, and dangerous pacts with technology that need to be made to get there (“you’re gonna take control of the chemistry/you’re gonna manifest the destiny”).

These secret exchanges between guitars and certain arcane machines have nothing to do with mere distortion. If that were the case, then ’80s metal would really be a demonic legion, instead of a hack-pack with only a few unholy stars. It’s subtler than that: The machines gotta be fucked with just enough to wake up and fuck back. Most of the really bad-ass barterings went down in the late ’60s and early ’70s: Blue Cheer, John McLaughlin, the first two Velvet discs, Stooges, Sabbath, Led Zeppelin II, Robert Fripp. But Hendrix was the unholiest of holies, the first, and perhaps the last, love magician to learn how to psychedelicize the machines themeslves.

If the Voodoo Chile got windowpane into his wah-wah, Sonic Youth got microdot into their microprocessors. But they’re too grounded in the electronic junkyard to drift off into deep space (“it’s total trash/and it’s natural fact”). They use these succulent, thrashing machines to tune into ’80s pop consciousness. They know the pop virus can be both lethal and divine, that if PKD heard saving graces through his Beatles records, Charles Manson heard insane mythic violence through his. The Youth are hip to the fact that today’s Sonic Matrix is saturated with signals and messages, and that music of vision is about being jacked in at the right nexus, with the right machines, picking up the right signals, and then just jamming the whole shit-stream into a techno frenzy of sexual fury and open-frequency psychic channeling (“transmittin’ all the time/lookin’ up to the skies/’I’m seein’ ghosts fly”). The revolution may not be televised, but the astral plane is, and the Youth prepare you for its hyperreal combat, armed with the data only pop esoterica affords. And you can hear shit in the overtones. We have met the dreaming machine, and it is us. (“all comin’ from human imagination/day-dreamin’ days in a daydream nation.”)

END