Messages; Bottles

Back in the early ‘90s, when I was working full-time as a freelancer, a simple allegory of the writing life came to me that has never quit: writing feels like painstakingly preparing a single, extraordinarily challenging page—an illuminated manuscript or a space station blueprint or a breakup letter in ancient Sumerian—then folding up said page into a paper airplane and throwing it out the window. Even though my writing is not especially personal, a lot of it still feels like a message in a bottle: a declaration of naked existence, tossed from the flotsam-clogged shores of this lonely and craggy isle in hope of . . . what exactly? Rescue? True human communion? A respite from the solitude required to write the damn thing in the first place?

That’s why it’s nice to get fan mail out of the blue. A shout out, a thank you, a thumbs up—it all helps scratch that deeper itch. That said, I realized long ago that, objectively, fan mail doesn’t mean squat about the quality of one’s work. Horrible, venal, and lazy writers with large followings probably get hoards more of the stuff than less horrible, venal, and lazy writers. So while I keep folders of all the letters, emails, and occasional bits of art I have received over the decades, I rarely return to them. For me the magic lies in the initial reception of the message, the unexpected smile from a stranger, and not in their accumulation.

Here is a sweet one I just got that felt extra groovy because of its acknowledgment of the paper airplane situation.

I just wanted to express my deep gratitude for your writing and lectures. Your thoughts, perspectives, insight, and extensive references to other material has been among the most powerful vehicles for my spiritual growth, my ability to make sense of things (mostly referring to carrying/navigating paradox in a curious and mysterious manner), and in my ability to see others ever so better as they are (while still swimming in delusion. haha). Your book, High Weirdness in particular has served as the fuel for restoking the flame of enchantment in me. . . . I’ve been in some dark places lately only amplified by the pandemic and I couldn’t be more grateful for you holding your hand out to help me navigate through your work. I’m not an author myself but I could imagine feeling a disconnectedness of not always sensing the extent to which your book is impacting people in a hugely positive way, so I just wanted to be exceptionally explicit that your work has had a hugely important impact on this guy here.

Right on! I appreciate the sentiment. Connecting with folks who resonate with my own anxious, overwhelmed, and occasionally entertaining attempts to wrestle down the Big Enchilada is one reason Burning Shore features the more-or-less monthly, subscribers-only letters column “Ask Dr. D.,” whose next edition, I promise, will be out next month. Of course, another reason I do the column is to give a premium bonus—essentially, a shot at my thoughtful attention—to those willing to fork over a subscription to this here more-occasional-than-I-would-like missive.

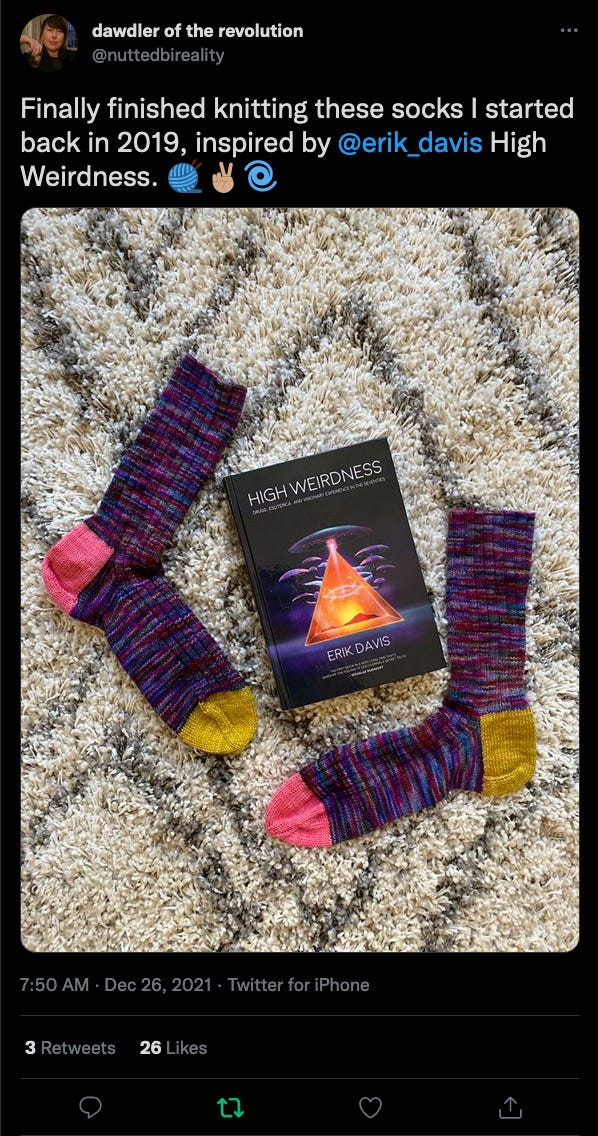

That said, I am of course also happy when folks respond to my stuff in completely unexpected, even goofy ways. It’s just nice to know that my existential trials manage to ripple through the vast pond scum of it all. Getting sampled in psybient mixes is pretty amusing (thanks Dr. Graham!), but really, nothing beats this:

I think I am not alone in wanting a pair, but I’m not gonna push my luck here.

Links

(•) Weird Gnosis

With a name like Weird Gnosis, how could you go wrong? And how could you keep me away? In December, the Netherland’s IMPAKT Centre for Media Culture launched a wonderful online exhibit of digital artworks, videos, and talks focused on “Media, medicine, and magick in a world out of control.” Marc Tuters, that rare European-based media scholar who has also spent unironic time on the playa, invited me to give a talk, and here are the results.

Please have a look at some of the pieces at the Weird Gnosis site, particularly Yin-Ju Chen’s “Extrastellar Evaluations III: Entropy: 25800,” Ellie Wyatt’s “Cherrypicker,” and Suzanne Treister’s “Technoshamanic Systems.”

(•) “When the Bridegroom Comes”

I am a huge fan and collector of Jesus Movement rock and folk music from the ‘60s and ‘70s, a fact that hardcore Erik Davis nerds know is related to the six months in high school I spent as a weirdo Jesus Freak—an episode I keep threatening to write about here on Burning Shore. In the meantime, here is an hour-long audio mix of west coast Jesus Music I prepared for the November edition of Radio Free Aquarium Drunkard. My brief chat with AQ’s most excellent Jason Woodbury, as well as the tunes, can be found at the 2:52 marker. For access to the full convo, consider supporting Aquarium Drunkard at their Patreon page.

Reading

You know those stoves where folks put stuff on the back burner? I’ve had to tear out the walls in my kitchen to make the place big enough for the range I need. In the last row, and to the left, sits a simmering pot that gives off a rank and rather sepulchral perfume: a project about weird fiction writer Clark Ashton Smith and what I am calling the California Weird.

Everyone knows about California noir, the home-grown genre of gum-shoes trawling the dark dregs of urban anomie, especially Los Angeles, the very definition of urban anomie. This hard realist tradition congeals the suspicion that all that California incandescence just makes the shadows more inky. No Beach Boys without Charlie Manson! Or is it the other way around?

The California Weird is dark too, but also more fantastical. The current begins with the famously bitter Ambrose Bierce, who, in addition to his sardonic (and esoterica-haunted) book The Devil’s Dictionary (1906), wrote a number of spooky tales, including an 1886 number that minted the otherworld “Carcosa”, later appropriated by H. P. Lovecraft (dread be upon him) and the writers of the first season of True Detective. But maybe the current starts with one of Bert Harte’s haunted gold-mining tales, or the Cherokee novelist John Rollin Ridge, or Robert Louis Stevenson, who spent time in Northern California as a penniless wastrel and set his fabulous “The Bottle Imp,” from 1891, in a San Francisco he knew was drowning in exotic decadence. It’s hard to know when things are born in the dark.

In any case, the California Weird passes directly from Bierce to his protegé, the San Francisco poet George Sterling, who also spent time building paganish altars in Carmel-by-the-Sea, where his friend, the poet Mary French, killed herself. A bon vivant and early Bohemian Clubber, the handsome Sterling earns his Weirdo badge for the purple molten majesty that infuses his poem “A Wine of Wizardry” (1907). From Sterling, who also killed himself, the stain seeps immediately into the far more fetid imagination of Clark Ashton Smith (dread be upon him, too), an impoverished resident of the Sierra foothills who wrote so-late-it’s-rotting Romantic verse before he started cranking out dazzling and dense cosmic horror stories for Weird Tales. From CAS it spreads to all manner of fantasists, very much including Fritz Leiber, a long-time resident who squeezed horror from the oil reserves down south in Venice (“The Black Gondolier” [1964]), and whose novel Our Lady of Darkness (1977) serves up a psychogeographic San Frantastic meditation on the very tradition I am sketching in this paragraph.

The California Weird is by no means restricted to genre literature. It casts a vast, visionary, and wonderfully corrosive network that includes the art of Cameron and Burt Shonberg, the poetry of Robinson Jeffers and Bob Kaufman, the music of Maitreya Kali and Arthur Lyman, the sculptures of Szukalski and tiki bars, the monsters of Ed Roth and Robert Williams and a myriad of subsequent lowbrows, the dark spells of Kenneth Anger and Old Scratch knows how many Hollywood Babylonians, like Bert Gordon, whose NEC’RO•MAN’CY (1972)—starring Orson Welles as a sorcerous cult leader—really freaked my adolescent shit when I stumbled on it some synchronistic Sunday afternoon on the wayward tube. And don’t get me started about Bigfoot and UFOs.

The California Weird is not so much a genre, as a mode of the place, an unsettling warp that makes itself known through cultural, psychological, and even environmental symptoms. I am thinking here especially of some writings of the dear departed Joan Didion, who had the haunted and bitter soul of a horror writer, and whose Slouching Towards Bethlehem is a key text of the California Weird in its nonfictional guise. Her piece on SoCal’s hot Santa Anas, which we call “devil winds” up here, is at once darkly mythic and oppressively tangible, the very equation of the weird:

I recall being told, when I first moved to Los Angeles and was living on an isolated beach, that the Indians would throw themselves into the sea when the bad wind blew. I could see why. The Pacific turned ominously glossy during a Santa Ana period, and one woke in the night troubled not only by the peacocks screaming in the olive trees but by the eerie absence of surf. The heat was surreal. The sky had a yellow cast, the kind of light sometimes called “earthquake weather.” My only neighbor would not come out of her house for days, and there were not lights at night, and her husband roamed the place with a machete. One day he would tell me that he had heard a trespasser, the next a rattlesnake.

Even in a famously placeless place like Los Angeles, local lore and local forces hold sway over the psychogeography of dread: hot winds, dead surf, vibrating preludes of the earthquakes the land holds coiled like an ancient rattler ready to strike.

This fall I discovered another slice of the California Weird by another woman wordsmith: Victoria Nelson, whose novel Neighbor George just came out from my good friends over at Strange Attractor Press (to whom I have also promised the final stew from that pot of Clark Ashton Smith). Vickie is a friend, and I met her for literary reasons—in particular, her absolutely excellent nonfiction book The Secret Life of Puppets (2001), which unearths the mystic and magical undercurrents hidden within modern Western entertainment and literature. Secret Life came out only a little later than Techgnosis, and I see the two books as highly sympatico. Both use scholarly chops and lively writing to unearth the spectral wire of gnostic esotericism animating pop culture. And though both books are thoroughly researched by para-academics, they are also similarly haunted by their own topics, elliptically transmitting the infectious truth: that the weird currents described withing can still draw you under, like a riptide sucking beneath the disenchanted surface of things.

Nelson went on to write another big think book called Gothicka (2012), which, while not quite as inspired as Puppets, makes a unique and important argument about how monsters have changed their stripes in our latter days. But though she is best known for these nonfiction forays, Nelson is also an incredibly versatile writer, having scribbled screenplays, personal essays, novels, and short stories over the many decades in which she also had the good sense to live a free and freaky life.

Neighbor George is an engaging and creepy horrorish novel that Nelson wrote in California in the 1980s. Somehow nobody bothered to publish it, which we may have benefited from in the end. Feeling frustrated by the reaction to her fictions, which probed “that interface between what is inside and outside, between the psychological and the metaphysical, the material and the immaterial,” she started to track that very same interface through Western culture, and the result was Puppets. Now readers can have their uncanny cake and eat it, too.

Neighbor George draws its marvelous sense of atmosphere from the years Nelson lived in the West Marin town of Bolinas in the late 1970s. Since the ‘60s, Bolinas has served as a hidden getaway for hippies and freaks fleeing the cities of the Bay. In the early ‘70s, having more or less taken over the Bolinas Community Public Utility District, the longhairs imposed a moratorium on sewers that forced a no-growth policy that radically curtailed development, allowing Bolinas to preserve the funky charm that still lingers in the air today, amidst the tangy eucalyptus funk and the silent whoosh of Teslas. Poets in particular were drawn to the area, which is not far from Stinson Beach, where the influential California poet Robert Duncan lived and wrote a decade earlier with his partner Jess.

For a taste of this rich and evanescent West Marin culture, you should get your hands on the newish 50th anniversary edition of the 1971 City Lights classic On the Mesa: An Anthology of Bolinas Writers. The book includes poems by residents and artful transients like Diane Di Prima, Joanne Kyger, Tom Clark, Philip Whalen, and Richard Brautigan, who killed himself there in 1984, but also pieces by a number of now obscure locals. It’s a charmed collection, almost less for the Beatly verse—some of which is powerful and moving—than for the rare sense of poetry as the potent coin of an actual realm, an interpersonal and imaginal medium of engagement and love and study that comes, for a short spell, to animate a place.

The poets who appear in Neighbor George are professional outsiders, but Nelson does a marvelous job of capturing the gently bohemian Bolinas milieu that prioritizes poetic performance and the spiritual erotics that surround it. She is even better in her evocation of the land, the peculiar magic of West Marin and the Point Reyes cape. This special area is one of the northernmost exposed chunks of the Pacific Plate in California, and lies just west of the San Andreas fault that undergirds the local lagoon—“final proof,” Nelson’s first-person narrator Dovey writes, “that Bolinas is situated in a realm apart, which was what I had always sensed about the little town to the north, and sometimes, in a very different way, about myself.”

Neighbor George invites us into the interior struggles of Dovey, who is intellectual and rather remote. She grows fascinated with George, the fellow who moves in next door to the family home which she is house-sitting, and which is filled with Bermuda Triangle paperbacks. I don’t want to tell you too much about what happens between Dovey and George, because that’s where the fun lies, but I will say that the story goes through some marvelous twists and turns—including one literal twist and turn that punctures the everyday veneer of the story with unsettling anomaly, and that now seems to have taken up a permanent home in my memory palace of Weird lit.

You could call Neighbor George a California Gothic, but Nelson also described her book to me as “anti-Gothic.” This point is worth explaining. As an obsessive reader, Nelson has absorbed many genres in her time, and the one most at play in Neighbor George is the modern Romance novel. The relationship between Dovey and George plays with and subverts the calculus of desire that drives these bodice-rippers, deconstructing it psychologically (in terms of Dovey’s relationship with her own father) and as a genre, as Gothic Romance gives way to Gothic Horror. This context may also help contemporary readers understand Dovey’s sometimes passivity, which, despite the strength and intimacy of Nelson’s portrayal of her protagonist, doesn’t always jibe with contemporary expectations of female agency. But that’s the point: this was the ‘70s, folks. Women and men sometimes invited strangers into their homes, just like they invited drugs and poems in: with curiosity, and naive faith, and sometimes stunned abandon.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar.

Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so please pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!