My Date with a Transvestite Spirit Medium

I do not have children, which saddens me a bit, for I would like some day to tell my descendents of the time I met Valiant Lord Kwawswa, the Burmese guardian god of rogues and vagabonds, on the hot and dusty planes of Mandalay. We were traveling in the month of August, J and I, and the sky was low and heavy with monsoon. Our guides had brought us to the town of Taungbyon, famed throughout the land for its exuberant nat pwea week of endless overlapping rites that honored, propitiated and feted the Thirty-Seven Nats, Burma’s earthy and melodramatic pantheon of all-too-human spirit beings.

The crowded central footpath through Taungbyon was flanked by food stalls, tea shops, and globalist collages of t-shirts and cheap jeans. A labyrinth of smaller paths radiated from this main artery, and beckoned us with clanging gongs, drum beats, and otherworldly folk-pop squealingsthe sonic signs that the nats were in the house, or, more accurately, inside the bedecked and spangled bodies of Burma’s incomparable spirit mediums. Following one of these paths, we stumbled upon a group of smiling women who invited us to join them inside a small stall set up next to a particularly boisterous orchestra.

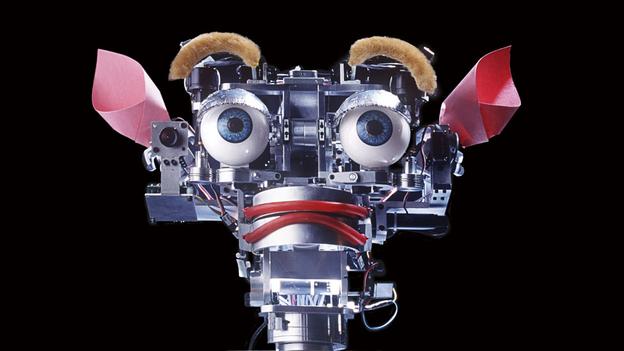

We settled down on the raised platform, joining what turned out to be a small and informal session with a spirit medium, or nat gedaw, who sat cross-legged before a lacy altar wearing a glazed, otherworldly look in his eye. Most of Taungbyon’s mediums are, in some manner or another, transgendered “ladyboys” in the local parlance. The nat gedaw before us was clearly a man, though he was dressed in an effeminate array of pink and white chintz and wearing a fetching orange bandana topped with a few crisp low-denomination units of Burmese kyat (pronounced “chat”). The medium smiled at us and silently directed someone to give us some fried chicken legs, stringy and vaguely repulsive and which I dutifully munched down for the both of us. The ladies moved aside, and encouraged me to shuffle up the medium, who gifted me with the first glug of what would become, by the end of the day, a veritable stream of Grand Royal whiskey.

Though I did not know it at the time, chicken and whiskey signify the presence of Ko Gyi Kyaw, also known as the aforementioned Lord Kwawswa, at least according to one the few documents on nat worship I have managed to scare up. Lists of the Thirty-Seven Nats are notoriously incomplete and contradictory; they are often composite figures, with multiple names, and there are well more than thirty-seven. Though the Burmese use the term nats to refer to both heavenly devas and local nature spirits, the Thirty-Seven are a spectral crew of former human beings, some quasi-historical and some obviously folkloric, who linger on in an astral antechamber of the earth, refusing to vacate the premises. They are a colorful lot, packed with princes and beauties, and nearly all left our world in wretched and excruciating circumstances, like self-immolation or leprosy or death by tiger. I can’t tell from my research whether Ko Gyi Kyaw died of drink or was buried alive, but his life course was firm, its debauched credowhich conjures Hafiz and 50 Cent in equal measurecaptured in this sample from one of his ritual songs:

Do you not know me? Have you not seen me at cock-fights? Have you not seen me letting off fireworks? Many times have I fallen prostrate in the gutter, drunken with my wife’s wine, and many times have I been picked up by the loving hands of pretty village maidens…

I needed my photo taken with this guy. So I ponied up 500 kyat and sidled up next to Ko Gyi Kyaw’s temporary vessel for a shot. Egged on by the ladies, I put my arm around the medium’s shoulder. His whole body trembled, a jittery pulse that reminded me of the characters in old Betty Boop cartoons. Taungbyon’s mediums are performers first and foremost, but this guy seemed to be deeply tranced out. Nobodyat least nobody normalwas home.

Our stall was well-placed to take advantage of the nearby orchestra, which was, as the kids say, going off. One drummer gripped a stick in either hand, rooting the rhythm with a primitive pulse, while another guy devoted himself to smashing cymbals together with seemingly careless ferocity. The heart of the orchestra was a circular drum station that allowed the bandleader to pivot around and strike twenty-odd small drums tuned with some sort of gooey clay. Two similar wheel-like consoles were devoted to brass and bronze gongs, tuned, more or less, to a major scale, with an odd half-step here or there. The shimmering and hysterical melodies of these gongs scampered dizzily over the monkeymind clank and clatter of the drums, with further bewitchment supplied by an ear-splitting oboe and wailing, mildly distorted vocals. It was the most mad-cap music I have ever heard, a brash and giddy bumblebee romp that called to mind a garage-rock gamelan orchestra banging out the soundtrack to some delirious and exotic Warner Bros. cartooncall it Daffy Does Devil Worship.

Dancing to these jarring and jittery beats, which shifted gears like Zappa at his wackiest, one bespectacled middle-aged woman in our stall became as one possessed. She started shaking, then began a sluggish stumble-dance, and finally dropped to her knees on the raised floor of the stall. A couple of older women immediately stopped their grooving and attended the woman with looks of great concern; later I learned they were attempting to prevent whatever nat had entered her body from staying too long and burning out her psychic circuits, or even killing her. Then, just as quickly as the entranced woman had slipped out our realm, her conventional personality returned. She had journeyed up to Taungbyon from her home in Yangoon and looked like she worked in an appliance shop or some other vaguely middle-class endeavor. “I was just hearing the music,” she explained. “I don’t remember…”

A few moments later, the nat gedaw, responding to no obvious signal or ritual resolution, hopped up, shed his sprinkly ritual garb, and returned to the standard Burmese male gear of a skirt-like longyi and a button-down shirt. He walked off without engaging the devotees, his gig as Ko Gyi Kyaw finished for the moment. As J and I wandered off, the nearby orchestra reached one of its delirious crescendos, a sound capable of waking the deador, perhaps more accurately, of those who continue to live through us.

***

I first heard about Taungbyon from Alan Bishop, the bass player and impresario behind the Sun City Girls, a long-lived postpunk jazzbo tantric freakout band with the largest and most diverse discography in the American rock underground. Along with perverse puppet shows and show-tunes covers, the Girls produce some fiercely psychedelic music, much of which both emulates and mocks the Middle Eastern, South American, and South East Asian sounds they love (check out Torch of the Mystics or 330,003 Crossdressers from Beyond the Rig Veda for a taste). This sonic exoticism is mirrored in their life, since both Alan and his guitar-slinging brother Richard, half-Lebanese boys who together make up two-thirds of the Girls, are inveterate Third World travelers. Alan first went to Burma in 1993 and has returned six times. He married a Burmese woman, and his adopted daughter, Thiri (pronounced “Theory”) helps create the charming and garish cover art for the bizarro world music CDs and DVDs that Bishop releases on his indispensable Sublime Frequencies label.

A few years ago, I visited the Bishops in their cavernous studio in Seattle, and they showed me clips from a DVD about Taungbyon that Sublime Frequencies later released. Shot and edited by the Bishops, Nat Pwe: Burma’s Festival of Spirit Possession is, like all of SF’s DVD releases, a surrealist anti-documentary, with no voice-over, odd visual juxtapositions, and none of the quasi-academic tone that afflicts so much official ethno cinema. While Alan’s notes for the DVD provide some solid context, the DVD just drops you into an alien world, its long takes inducing that peculiar mixture of boredom and ignorant amazement that travelers experience when they stumble onto the unpackaged exotica of distant lands. Along with incredible music and tantalizing close-ups of weird puppets and young girls, the DVD captures scores of sacred ladyboys cavorting about in gaudy finery, swilling whiskey, smoking scores of cigarettesoften at the same timeand throwing money around. It looked like Southeast Asian voodoo, and my reaction was immediate and unbidden: This I have to see.

Of course, visiting Taungbyon meant visiting Burma, and as a well-seasoned but hardly intrepid traveler, the idea of entering Burma produced a creeping feeling of unease. This mild sense of dread emanated as much from the opprobrium of political incorrectness as from fears of guerilla bombs or anal parasites. One of a very small number of old-school military dictatorships left in Asia, Burma renamed Myanmar in 1989 by the ruling State Law and Order Restoration Council remains a pariah state that practices forced labor, massive censorship, and a corrupt and criminally irresponsible economic policy. In other words, Burma resembles most developing countries, except for the fact that its generals don’t play ball with multinational corporations or, by extension, most nation-states. The famous democracy activist Aung San Suu Kyi, currently under house arrest in Yangoon, long ago asked foreigners not to visit the country, and many potential western tourists, especially from English-speaking countries, continue to honor her request. But many Burmese who hunger for democracy disagree with Suu Kyi on this point, arguing that foreign visitors provide a flow of desperately-needed dollars to ordinary Burmese and also make violent mass repression less likelyat least in the parts of the country that tourists and their cameras are allowed to visit. With Alan’s encouragement, J and I decided to take the plunge, though the news that forced labor helped refurbish some key tourist destinations, like the Mandalay Fort, hardly quelled my anxiety.

Burma’s air of the forbidden only thickened when the Myanmar embassy in Bangkok mysteriously rejected my application for a visa, which I had submitted via the travel agents on the horrible Kao San Road, a Lonely Planet bardo where all self-styled “travelers” eventually wind up whether they want to or not. The visa police, it seemed, had zeroed in on one particular letter of the English language scrawled on an old Indian visa glued into my passport: J. As in journalist. So we dutifully hoofed it to the embassy, where, after bathing in the wan fluorescent lights for hours and suffering an occasional insulting outburst from a sniveling French asshole who insisted that Americans had no business traveling anywhere at all, we were informed by a flabby-faced gent with a dull green uniform and poor English that journalists were simply not allowed into Burma. Persisting, we talked with Miss Miu, a young educated woman with sexy librarian glasses who suggested I type up and submit a formal promise that I would dig no dirt during my stay. The fax, written with pointless irony, did the trick, and a week later, I got my visa. The lure of the tourist dollar, it seems, can still tickle the fancy of a paranoid military junta.

Buffalos, Toe called them, as we drove into Yangoon. Toe had hopped unbidden into the passenger seat of our cab as we were hustled into the vehicle following an elaborate hand-off between numerous airport touts and starch-shirted operators whose choreography I can by no means reconstruct. A sharp-eyed and wiry guy, Toe spoke openly about the country’s woes and the corrupt lugheads in power. “They do not watch CNN, they do not know media, they are just buffaloes fighting in a field, eating, sleeping, getting rich.”

As you might have guessed, Toe also turned out to run a tour agency, Ko Tar Travels & Tours, and he offered to hook us up with a car and driver during our stay. Most western tourists in Burma avail themselves to a car and driver, and occasionally an additional guide. The practice is inexpensive, convenient in a land starved for infrastructure, and turns over fewer dollars to the government, which owns and operates the rails, which Toe called “the buffalo train.” With their beat-up cars and convoluted English, Burma’s freelance cabby guides have now paved an ad-hoc tourist circuit through the country, one that is regularly plied by the French, Germans and southern Europeans that made up the vast majority of the country’s western tourists. As first-time visitors, J and I were happy to follow most of Toe’s recommendations—Inle Lake, Kalaw, the Pindaya Caves, and the world-class Pagan. All we insisted on was a side trip to Taungbyon during the climax of the festival, which finds its close at the fullness of the moon.

***

Jasmine flowers dangled from the rear-view mirror of our dented white sedan, which was driven by a gruff-looking middle-aged guy with fat aviator shades. He had previously served as a captain with Burma’s merchant marines, sailing across the globe and seeing far more of the world than most Burmese, and this was his first trip working the tourist circuit. He spoke little English, smoked at every stop, and laughed with sardonic good humor. I scribbled down his name, but we just called him “the Driver,” after the nameless James Taylor character in Monte Hellman’s classic road movie Two Lane Blacktop.

In the passenger seat, taking up the Dennis Wilson role, was Thi Ha, who called himself Lion. A youthful fortysomething who had been plying the tourist circuit since he was a teenager, Lion had an infectious grin, a pronounced limp, and a temperament that veered between boisterous good humor and a sullen brood, the latter of which was not infrequently triggered by the Driver’s philosophy of manual transmission. Because he usually acted as a driver rather than an official licensed guide, Lion was not overflowing with facts and figures, which was occasionally frustrating but largely a relief. Like many folks his age, Lion had spent some hard years in prison after the massive democracy demonstrations of the 1980s, but seemed more sad than bitter. He was good folk.

On the way out of Yangoon, we drove by Shwedagon Paya, the holiest pagoda in Burma, an enormous golden Hershey’s kiss topped with a tinkling finial peppered with sapphires, emeralds, rubies and diamonds. As we passed the paya, the Driver picked both hands off the wheel and offered a short and somewhat alarming bow. A creeping feeling of uncanniness grew inside me. Was it the billboard advertisements for Dagon beer, an alarm for any Lovecraft fan? Or could it be the garish yellow pancake makeup, derived from the thanaka tree, that many Burmese women applied in sometimes fantastic designs across their faces? Then I realized that what had unnerved me was the total absence of multinational branding, as if the crumbling city lay in some parallel dimension not yet colonized by Coke and VISA and McDonalds.

We headed north towards Mandalay through leagues of rice patties, stopping for the night at Mothers House hotel, where we watched Burmese music videos, including a delirious homage to a tractor factory that featured pom-pom wielding cheerleaders. Go team! The next day we turned east, climbing up terrible roads into the mountains that cradle Inle Lake, probably the most popular destination for domestic tourists in Burma. Before arriving at the lake, we stayed a night in Kalaw, a lush mountain town of pine trees and bougainvillea gardens and military training facilities. After disturbing dreams, I awoke early in the morning and took a walk. The glass shards that covered the bell-shaped pagoda in the center of town sparkled in the rising sun, its square base decorated with four elven-eared devas that represented the heavenly strain of nats. Across the street, nestled in the trunk of a sprawling banyan tree, a coarse and far more earthly nat stood within a locked shrine.

As I turned from this rough idol and made for the mosque on the south side of town, I was greeted by two grizzled characters lounging against a wall, the sort of folks we called “tuddies” in high school. One guy was large and fleshy, and made a stark contrast to his scrawny buddy, who sported an Islamic beard and a long thin early riser cheroot. The mouths of both men were a crimson holocaust of betel rot. The big fellow was drunk, and was dead set on letting me know, in no uncertain terms, just how fucked up his country was. “We are under the boot, like Germany, like Gestapo,” he growled as his mute and grinning friend enthusiastically bobbed his head in agreement. “They have taken away our human rights. You should tell the BBC.” So for a moment, dear reader, please pretend that you yourself are the BBC.

Inle Lake is a long and luxurious body of water nestled between two soft mountain ranges. The area was gorgeous, and, more to the point, relaxed. The traffic in the main town was still largely restricted to bicycles and scooters, and there was enough of a tourist infrastructure to produce a decent Italian restaurant but not so much that it spoiled the scene or the goodwill of the folks who lived and modestly prospered there. The lake itself was peppered with floating gardens, villages on stilts, and fisherman who steer their boats with their feet—an image that serves as the icon of the region, like gondoliers in Venice. One inevitable but worthwhile stop was the Jumping Cat Monastery, a gingerbread teak compound that hovers over the lake atop rust-red stilts and houses felines that smug and vaguely disdainful monks have trained to leap through hoops on command.

Lion had a good friend in Inle town named Linn, who served as a freelance trekking guide besides waiting tables at the Italian joint. One morning, after we visited a village market overflowing with pickled tea, jackfruit tar, and pornographically flayed fish, Linn took us into the mountains. He sported floppy Converse trainers he had scored from a European client, and a baseball cap that made him look like a runty Tiger Woods. Like Lion, his good humor was leavened with a sad and somewhat traumatized air. At one point during our muggy hike through fields of turmeric and tobacco, we passed a young peasant couple and their small grubby child. After they passed, Linn stopped, his eyes brimming with tears. He came from a poor village himself, and though he tried to educate the villagers about medicine and birth control, he knew there was little hope of vanquishing Burma’s vicious circle of rural poverty and ignorance.

Later we were invited to a meal at Linn’s home. We expected to eat en famille, but instead found ourselves a twosome at a candlelit table on their dirt driveway. I was already feeling the first rumblings of the gastro-intestinal bummer that would vex the following few days, the result, I expect, of the delicious pickled tea we had eaten for lunch at the mountain village. But I valiantly dug in, and enjoyed our best exposure yet to Burma’s hybrid and rather unspectacular cuisine: a pepper soup, sprightly greens, sweet-and-sour veggies, thickly curried prawns, and weird chunks of fried fish.

Afterwards, we were taken inside and shown the family nat shrine, which prominently featured as altar for Maha Giri, the Lord of the Great Mountain. Shrines to Maha Giri appear in every Burmese home, or at least those that still traffic with the nats. A small curtain was drawn before the Lord, here embodied by a coconut tied with a red kerchief. The reason for the curtains is that, when Maha Giri was a mortal hero, the King of Taguang ordered him tied to a champa tree and burned alive, and so he does not care to see light at night.

I had gleaned this bit of lore from a grimy reprint of Maung Htin Aung’s Folk Elements in Burmese Buddhism, which I scored in a no-less grimy shop in Yangoon, and my datapoint made enough of an impression on Lion that he joined us at the table with a bottle of whiskey and talked about the nats. Lion estimated that only thirty percent of Burmese believe in the nats. He was brought up within the other seventy percent; though many Burmese worship the Buddha alongside the nats, Lion’s parents believed that the dharma was incompatible with such popular supernaturalism. The strain between the two faiths goes back a millennium, to the imposition of Theravada Buddhism by Pagan’s sanctimonious King Anawrahta in the 11th century. Anawrahta disliked the nats, but was unable to suppress their worship, and so, like the Catholic church in the heathen colonies, he assimilated them. Against the riot of popular lore and orgiastic rites that proceeded the dharma, King codified and established thirty-six nats, headed by Maha Giri, at his central paya in Pagan. Anawrahta then crowned the posse with a thirty-seventh natthe deva Indraand thereby symbolically placed the nats under the Buddhadharma.

Lion explained that many Burmese worship the Buddha in order to guarantee a good future life, while they propitiate the nats in order to reap rewards and avoid calamity much of it caused by the natsin this world. Lion then admitted that he began serving the nats after he hooked up with his wife, whose mother was a strong devotee. Nats often communicate in dreams, so when Ko Myo Shin came to Lion one night while he slept and said “I want to be in your home,” he went out the next day and bought a shrine. In exchange for taking on some of Ko Myo Shin’s restrictions she does not care for either beef or pork and wants her devotees to abjure the same Lion was eventually gifted with dream transmissions of some winning lottery numbers. But the nats can also be as petulant as children, and their propitiation is a two-edge sword. One day Lion fell off a low wall and inexplicably broke his leg, which healed badly and continues to cause him chronic pain. He blames the whole incident on the shirt he wore that day, a black rocker T with a buffalo head on it. Lion believes the garment offended a nat named Popa Medaw, who has a thing about buffalos and the color black.

As the cries of the crickets and bullfrogs rose to a deafening keen in the Inle air, Lion, now in his cups, revealed that he once lived with a ladyboy who had embarked on the path of the nat gedaw. Lion learned some of the ritual nat dances from his friend, and became quite proficient at some of them. He insisted that lots of mediums were in the game just because they liked to dress up and dance (and, presumably, to make some decent money). Only a small number of nat gedaw, he claimed, were the real deal, capable of genuinely invoking and holding these powerful spirits in their bodies without going crazy or becoming sick. As the evening wound to a close, I could not resist asking what the deal was with all the cross-dressing. Lion’s answer was crisp: “Nats prefer ladyboys!”

***

A week later, J and I were packed in the car with Lion and the Driver, inching our way past the wide fields of rice patties that lie north of Mandalay. We had left our grotty urban hotel mid-morning, as the touts for the taxi-vans filled the air with cries of “Taungbyon! Taungbyon!” Vehicles piled with eager passengers were already alighting, hoping to avoid the traffic that would later choke the route to the nearby town. Along the way, we found the road lined with beggars and cripples and clumps of people attempting, with widely varying degrees of conviction, to extract road tolls and donations, the latter elicited with heavily reverbed bullhorn entreaties and small children tossing “coins” (no longer part of the money system) inside silver bowls. Even before we reached town, with windows rolled up against the dust, we sensed the crackling, eternally returning energy of festival. A few dreamtime shivers struck my spine, and I recalled the pothead rush of anticipation I felt as a teenager arriving at Grateful Dead parking lots that electric sense that a luminous collective secret was about to open to all.

J and I left Lion and the Driver in the parking lot, where they would wait like bored soldiers for the next half a day. We walked into a dusty, unkempt scene that resembled nothing so much as a South Asian county fair. The main streets thankfully devoid of cars were lined with stalls offering gelatinous sweets, flowers, cassettes, greasy treats, and shoddy goods. Kids ran around gobbling candy, and a manually-operated Ferris wheel loomed behind the village’s central paya, the attraction’s upper struts lined with young men prepared to generate momentum by hurling their bodies earthwards while holding on to the spokes. Inside a roomy nearby stall, behind a single rickety turnstile, a troop of large stick puppets fought out a gory domestic drama to a prerecorded soundtrack of spooky B-movie chords and heavily distorted Burmese piano doodles. Outside, the piles of coconut husks and banana leaves the refuse of a brisk trade in offerings reminded us that this low-key rural carnival was in some sense sacred. But there was no heaviness of purpose among the crowds, no gloomy pilgrim piety, no religious mania.

The casual, boisterous atmosphere saturated Taungbyon’s central paya as well, where crowds decamped on the floors of open halls glittering with mosaics of silvered glass. The pagoda plays a crucial role in the story of the Taungbyon brothers, the two nats who lord over the town and its annual pwe. Shwepyingyi and his brother, possessed of the amazingly similar name of Shwepyinnge, were the sons of Byat-ta, a “mighty man of endeavor” employed by King Anawrahta. Byat-ta, along with his brother Byat-wi, had been discovered floating in a sea-born basket by a monk. While he was raising the orphan boys, who had Indian features and were considered Muslim, the monk chanced upon the corpse of one of Burma’s myriad alchemists, who spent their time concocting elixirs of immortality and fighting magical battles over the fruit-maidens they liked to fuck. Knowing the extraordinary powers imparted by cooked alchemist flesh, the monk promptly roasted the dead body. He then commanded Byat-wi and Byat-ta to guard the corpse while he fetched the king. But the young brothers could not resist the aroma of the flesh, and so gobbled the entire alchemist, becoming superheroes in the process.

Anawrahta grew to distrust both brothers and eventually killed them. But after murdering Byat-ta and his ogress wife, the king took pity on their two sons and raised them in the court. Because the boys had inherited some of their father’s superpowers, they were later ordered to lead the king’s army into China to seize the empire’s Buddha relics, which Anawrahta believed would help him banish the nats from Burma. Unfortunately, the lazy brothers brought back a jade replica of the Blessed Molar instead of the real deal. Later, when the king ordered the brothers to help construct the pagoda at Taungbyon, the two men decided to play marbles instead. This was too much for Anawrahta, who castrated the guys with a magic spear and let them bleed to death. From beyond the veil, the brothers, now nats, continued to hassle the sovereign, and the King eventually made the them the spiritual lords of Taungbyon. The annual pwe held in their name grew and grew, and when a later sovereign, King Mindon, proclaimed that he would cancel the festival, the two nats made his balls swell until Mindon relented.

Passing through the thronged halls of the paya, where a few missing bricks intentionally recall the brothers’ fateful goof-off, J and I entered a crowded courtyard and plopped down on a mat beneath the scant shade of a scrubby tree. It was hot. An old woman danced nearby, mad or possessed or both, and a troop of uniformed authorities moved through the crowd, snarling at people and taking notes on an immense form attached to a clipboard. Almost instantly, we were absorbed into a group of folks sitting in the shade of a small stall besides us, waiting for their turn at dancing and propitiating later that evening. They seemed like an extended family or friend network ordinary folks just having a picnic. A few attractive young ladyboys sat mincing in their midst, integrated into the scene in a manner unimaginable in the west. They fed us greasy rice fried with cardamom, even greasier fish, and fat purple banana coconut treats. J swapped an arm band for cheap gold chains and bracelets, and I performed for the crowd by rolling some of the loose Virginia tobacco I had purchased in Bangkok, a wise move which saved me from the ignoble fate of smoking foul Chinese cigarettes.

We left our new friends and walked towards the Ferris wheel. Along the way, we passed a small crowd intently clustered around some curiosity we could not see. Even before I peered over their heads, I felt the foreshock of the bizarre, and indeed the curiosity in question turned out to be a magnificently deformed kid with an enormous peanut-shaped head almost the size of a horse skull. From the yellow dress it seemed this person was a girl. Though her handlers did not seem be gouging the crowd for kyat, the pitiable being was clearly on display, as she lay on a cot in the shadow of an umbrella, beaming beatifically into the void. I was tempted to videotape this strange and in some way touching scene, but some force stayed my Monde Cane hand. And, with this shocking sight having inadvertently opened our minds to the weirdness always within our midst, we passed from the paya and made our way toward the maniac beats and wailing reeds of the distant orchestras, calling down the ghosts.

***

In 1710, Alexander Hamilton, a British seaman visiting Burma, wrote in his journal about the oracles who performed at a sacred feast he attended. Though the event he described could have reflected another popular tradition, it sounds an awful lot like a nat pwe.

I saw nine dance like mad folks, for about half an Hour, and then some of them fell into Fits, foaming at the Mouth for the Space of Half an Hour; and, when their senses are restored, they pretend to foretell Plenty or Scarcity of Corn for that year, if the year would prove sickly or salutary to the People, and several other Things of Moment, and all by that half hour’s Conversation that the furious Dancer had with the Gods when she was in a Trance.

Though such powerful possession cults still exist in Southeast Asia, the rituals at Taungbyon now seem rather tame compared to Hamilton’s account, with formal dances replacing epileptic jitters and mantic drool. Today’s mediums still dispense predictions, although advice on love or money have replaced the corn forecasts of yore. However, in one crucial way, the tradition Hamilton saw has not changed at all. When it came to the gender of the oracles, the captain wrote, “Hermaphrodites, who are numerous in this Country, are generally chosen.”

Make no mistake: for one curious week in August, Taungbyon is tranny city, although you would not know that from reading some of the sources. In Burmese Supernaturalism, which was published in 1978 and is probably the most thorough book on the subject available in English, Melford Spiro goes into fascinating detail about Taungbyon’s nat gedaw. He claims, though, that they are almost entirely women, while “experts at Taungbyon estimate that three to four percent are male “most of which, he adds, are homosexual or transvestite. Now, the realm of the transgendered is tough to clarify and categorize; given the endless permutations and tangles over nomenclature, biology, and sexual orientation, the liminality of the dual sexed makes itself known in all discourses that approach the subject. Nonetheless, I can’t imagine who Spiro’s “experts” are, or how the author could have missed the signs familiar to any tranny fan. Because if Taungbyon’s nat pwe today is anything like the pwes Spiro visited in the 1970s, ladyboys whether cross-dressers or more hormonally-driven hermaphrodites dominate the sacred congress between nats and human life.

In the modern west, people celebrate tranny culture, when they do, because of the way the transgendered scramble and expand forms of sexual identity and erotic possibility. But many traditional cultures have recognized that transgendered folkswhether “homosexual” or something more ambiguous also have a sacred and numinous power. From the primal hermaphrodites of Chaldean and Gnostic myth to the mystic cross-dressers of South Sulawesi to the Native American berdache or “two-spirit,” who often serves as both an oracle and healer, transgendered people have the power to pass between the worlds, to draw down the gods, to penetrate and contain the cosmic mystery sustained by the primal polarity between masculine and feminine. On the most mystic level, the transgendered being embodies the coincidentia oppositorum, the union of opposites effected in the alchemical androgynes of German spiritualists like Jacob Boehme and Franz von Baader, and later of Jung. Here the anatomical wonders of the ladyboy monstrous to some are spiritualized into a “perfect man,” an Adam Kadmon characterized by a primal wholeness that lies beyond gender.

The sacred hermaphrodite is a cross-roads being. Holding masculine and feminine in her left and right hand, he is also characterized by another, more vertical polarity: between the “higher” spiritualized androgyny of perfect union and the polymorphous eroticism of the sexual depths. So while Burma’s nat gedaw certainly serve an oracular and even sacred function, they are also hip-deep in the erotic. According to Spiro, who makes curious asides about the temptations of “bottom-pinching” stirred up by Taungbyon’s crowds, the nat gedaw are often initiated into their future roles through sexual visions. Like medieval incubi, nats often approach their future servitors in dreams, seducing and then fucking them. Most people so approached marry their nats ritually and become mediumsnat gedaw means “nat spouse.”

For most, there is not a lot of choice in the matter nats are capricious and vengeful playas, and it takes a lot of guts to reject their advances. Sometimes the nats allow their new spouses to continue ordinary sexual relationships, but mostly they jealousy demand fidelity. From a more sociological perspective, the call of the nat serves as perfect cover for individuals born into Burmese society who do not confirm to standard heterosexual identities; the role of the nat gedaw offers “the third gender” an avenue toward status and financial power otherwise nearly impossible to achieve. At the same time, they continue to carry a transgressive and threatening sexual charget hough the nat gedaw are respected for their oracular skills, they are also suspected of being promiscuous sluts or even prostitutes.

To J and I, the nat gedaw largely seemed like voodoo voguers, exuberantly kicking up their heels in the superstitious limelight. After squeezing through the crowd that thronged one pwe enclosure, J and I were approached by a friendly character wearing a baseball cap and a lime-green Hawaiian shirt decorated with dolphins. With the proud air of a successful entrepreneur, he invited us to join his extended family inside the enclosure for the next pwe, which he had sponsored. A sponsor like him might pay around 200 bucks to rent the stall and hire the orchestra and the mediums, who often accompany the sponsor from his home town (the orchestra stays put as different mediums and sponsored groups come and go). The sponsor’s fee does not include the whiskey or cigarettes consumed by the nats and occasionally dolled out to the devotees who crowd the floor between the orchestra and the altar. Nor does the fee cover the wads of crisp, small denomination bills that the mediums in turn throw at the crowd, who lunge for this “lucky money” like contestants at a game show.

J and I followed the sponsor into a dark, musty room that abutted the enclosure, where the two nat gedaw he had hired, bedecked in elaborate head gear and lacy white robes tied with thick red sashes, were quietly waiting their turn on the stage. The boss medium must have been in her fifties, a shriveled and leathery ladyboy, imperiously fanning herself in the gloom. Her partner was younger, moon-faced and attractive, her prettiness marred only by severely betel-rotted teeth, although whether this imperfection is seen as such by the Burmese I cannot say. As I posed for a photo with these two ladies, the Hottie reached behind my back, grabbed my hand, and placed it firmly on her hip as she gave me an alluring glance. When we parted, the imp of the perverse who lies within us all could not resist giving her hip an unseen squeeze.

We were ushered into the main pwe enclosure, a large blue stall surrounded by fences on three sides, its roof strung with multicolored Christmas lights. The altar was crowded with a handful of mannequin-sized idols, tons of flowers and bananas, and a small Buddha in the corner, reminding those who cared to notice who was theoretically in charge. Things got rolling when the Boss performing a stylized sword dance for Maha Giri. Small flags decorated with rabbits and moons were then trotted out and twirled, and finally the two mediums faced the altar and lightly flagellated themselves with bunches of green ferns as they offered up little hip shimmies. A long series of dances followed, with each medium alternately taking the lead. The Boss or the Hottie would call out the tunes associated with various nats, the appropriate ritual implements would be placed in their hands, and then they would dance curious moves that simultaneously invoked the nats, propitiated them, and allowed those disincarnate beings to temporarily get a groove on.

At regular intervals, the two mediums would toss lucky money at the small crowd, which was mostly made up of women sitting cross-legged on the ground. The devotees offered up warm cans of soda to the nats, or liberally sprayed their living vessels with cheap perfume treats that soon gave way to London cigarettes and Red Sea rum. Others would rise and pin bills to the lacy robes and glittery headdresses of the nat gedaw. Large denominations were likely to elicit private words of advice, which usually concerned the appropriate nats to propitiate for success in love or business. As they accumulated kyat on their costumes, the mediums took on the character of androgynous birds, their feathers composed of one of the more comical currencies on the planet.

The nat gedaw certainly commanded all the attention, but they were not exactly in charge. Their ringleader was a rail-thin young man who acted like the pimp-daddy manager of a pair of soul divas, keeping one eye on the clock and the other on the cash. He looked like a genie, the nails on his right hand as long as claws, his many rings a garish brand of mystic bling. Radiating the condescending pride of a hustler, Mr. Bling seemed completely unmoved by the presence of the sacred forces in his midst. Without a smile, he collected notes from the crowd in a small silver pot that he then handed to the Boss, who proceeded to dance the gambling dance of Ko Gyi Kyaw, magically suspending the pot between her hands like an ace juggler.

As the rum continued to flow, the Hottie began to direct her attentions toward yours truly, and the mischievous squeeze earlier in the afternoon flowered into full-scale public flirtation. I knew all bets were off when she came up to me, demurely turned her head away, and invited me wordlessly to kiss her neck, which the imp of the perverse performed with alacrity. The act produced gleeful cheers from the crowd, including the profoundly amused J. When I next turned toward the orchestra, one of the male singers a sweaty, vaguely feral guy whose thinning hair was pasted to his forehead caught my eye. Through winks and gestures, he let me know that the real trick when offered nat neck was not to kiss but to inhale. He mimed a sniff that embodied, at least at that drunken moment, a heartfelt prayer for carnal deliverance and release. Ten minutes later, after the Hottie had bestowed a soft peck on my cheek, she again offered me her neck. I took the fellow’s advice and huffed. And there, in that late afternoon air, thick with particulate matter and sweet perfume and pungent sweat, I was delivered unto an aromatic pureland, some far field of ambrosial incense and flowering trees where the Buddhas teach by scent alone.

The rite closed with a long series of false denouements, as the nats refused characteristically, I would learn to disembark from their vessels of flesh. The Hottie kept calling more tunes, although it was no longer clear whether she was guided by the spirits of the nats or the ethanol. Calming down his ladies, dabbing off their sweat in a vain attempt to keep them looking regal, Mr. Bling seemed to grow annoyed, although his irritation may have been as ersatz as outrage at a WWF meet. As the orchestra mimed a rock band in an eternal drum roll climax, one woman responsible for much of the cash flow throughout the afternoon went into trance: flailing limbs, wiggly eyes, wacky-assed dancing. After the mediums had brought her back, the Hottie tried to do something with the money the possessed woman had earlier given her. The proceedings were obscure, but the woman leapt up and began arguing passionately with the Hottie, until the Boss and Mr. Bling came over to straighten things out.

At this point, the most powerful supernatural force that animated these rites came to the fore: cash. Many of the folks around me had scrimped the entire year in order to splurge at the nat pwe, believing that their offerings would bounce back to them in the form of luck or lottery numbers or good business. Now the liberal economy of the earlier “lucky money” phase, with its free-for-all distribution of small bills, gave way to a more retentive logic, as the mediums paused amid their chaotic dancing to count their accumulated cash with the finesse of bookies and dole out chunks to the singers and the orchestra. Clearly unsatisfied with the numbers, the nats aggressively focused on the further extraction of cash from their devotees, affecting an attitude of haughty privilege no doubt designed to stimulate the superstitious awe of their temporary acolytes.

As wealthy westerners, we were inevitably drawn into this monetized game of seduction and command. I had been recording the event with both a Sony video camera and a small Canon Elf, and I happily handed over a small wad to the various musicians I had recorded. But I was not satisfied with the footage I had shot of the Hottie, and so, in order to coax her to perform for the camera, I kept slipping more money into her garb, soon switching from kyat to single dollar bills. As she wised to my game and began to deliberately turn away from my camera, I realized that this exotic Burmese possession rite had become something much more akin to a strip show. Given all the attention and money I had paid to the younger medium, I should not have been as surprised as I was when a jealous Boss stepped up and aggressively demanded three dollar bills. As this transaction occurred, the Hottie started rifling through J’s bag in search of more greenbacks, and only narrowly missed the twenty that J had expertly palmed. Yanking out a copy of Orwell’s Burmese Days, the Hottie looked utterly disgusted and threw down the book.

Finally the orchestra quit and the crowds dispersed. The Hottie approached me and coyly cupped her hand near her mouth, as if feeding herself rice, and I realized she wanted to eat with us, or me at any rate, or me and my wallet. But before my imagination could grapple with the quantum wave form generated by this invitation, Mr. Bling put the kibosh on the whole affair, whisking away his nat gedaw in the blink of an eye. J and I wound up eating with some of the people who manned the pwe stall. They served us rice and vegetables and a dish featuring Burma’s classic stanky fish sauce, which should certainly be sampled by all lovers of Marmite. We had great fun as these disarmingly friendly folks schooled us on how to eat the clumpy sauce-soaked rice with our hands, a procedure that involved flicking the moist clump of kernels into your mouth using your thumb as a kind of shovel. As I practiced this move, I briefly thought of the Hottie, even as I most likely picked up the bug that wreaked havoc on my gut for days thereafter.

Sated and still blazing from the pwe, J and I wandered through the early evening, surrounded by droves of young trannies, flirty but sweet, dressed to the nines. These ladies were not channeling the ghosts of ancient heroes but were here to strut their own stuff, and they lovingly vamped for our cameras, which to my eternal horror had ran out of juice. Though J and I were still sloppy from our earlier slugs of nat whiskey, we finished off our own bottle, huddling in the dark as the crowds thickened around us. Over the next few hours, we dipped into a handful of pwes, and I tried and failed to track down the one great tape by a Burmese metal act called Iron Cross. After visiting the main nat temple, where we stumbled over a drunken propitiator flopping around a pile of ferns beside the huge booming speaker stacks, we called it a night. Lion had pleaded with us not to stay after dark, but the crowd seemed perfectly mellow as we returned to the car. Then Lion and the Driver whisked us away, relieved less for our safety, I suspect, than that their long day was finally done.

***

The night before we departed from Yangoon, we stayed in a hotel near the Shwedagon Paya so we could walk up to the holy site in the early morning. Shwedagon crowns a steep hill and is approached by four long stairways that lie in the cardinal directions. We chose the north approach, which does not have an escalator or elevator and is crowned at the top by a guardian ogress. There she sat, like a proud and hideous fishmonger’s wife, surrounded by an enormous pagan array of green bananas. Someone had stuck a burning cheroot between her fleshy lips.

Shwedagon is a world-class sacred spot, a peaceful palimpsest of Burmese spirituality, with equal measures of supernatural pop, alchemical esoterica, and energized Theravada Buddhism. The paya itself sits in the middle of a fourteen-acre-square platform that hosts an impressive array of pagodas, platforms, pavilions, shrines, and 3-D murals. The crowded, helter-skelter deployment of the these structures, as well as the riot of eras and styles represented, give the site an eclectic, urban feel despite the pervasive air of gentleness and calm. That morning the place was crowded with ordinary folks, and their range of attitudes and practices, from silent meditation to the ritual bathing of rodent idols, suggested a casual democracy of the spirit.

The paya itself sat like a Buddha at the center of the square, an enormously fat and pointy bell topped with a gold-plated umbrella that tinkled distantly in the breeze. The gold leaf that coats the massive form was mostly muted beneath the overcast skies, though occasional blasts of skin-crisping sunlight brought the surface to blazing life. The stillness embodied by the paya reminded me of the implacable tranquility of the great Gothic cathedrals, but rather than the medieval sense of hushed interiority, this huge tapered thing was all surface, sitting squarely in the midst of the bustle, its windowless mass embodying an architecture of meditation. I climbed up a small platform near the paya, and sat silently among the astrologers and shop-keepers, meditating on the melancholy of departure.

As we hustled back to our hotel to collect our luggage and leave, we counted the small amount of kyat that remained in our pockets. Rounding a corner near the hotel, we came upon a young man holding a cage filled with sparrows. Five hundred kyat, the last of our lot, would buy us the right to release three birds and thereby stock up on some merit, an empty but poetic act of exchange that seemed as good a way as any of dispensing with this nearly worthless paper. The guy placed two birds in my hand, and they immediately took to the air. Then he set one sparrow on J’s open palm, delicately lined like an old soul’s, and the bird just sat there, perfectly content, like there was nowhere to go. But our flight would not wait, and so J softly shook her hand, and the sparrow rose into the glowering skies.