Rome’s great pagan building

There are scores of amazing cities on this planet, but Rome is the one European urb I had yet to visit that really called me, and it called me, most of all, because of one building. The Pantheon is often called the most solidly preserved remnant of ancient pagan Roman architecture, and moreover a temple to a principal — eclectic or synthetic depending on your leaning — that has long attracted me: all gods. Everyone into the pool.

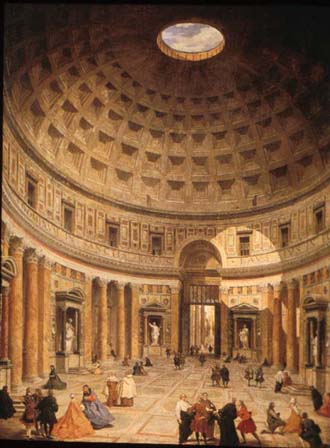

Though the exact function of the temple in its pagan days remains unclear, the seven planetary deities that once stood in its interior niches spoke at once for the polytheistic exuberance of the ancients and the properly cosmic aspirations of the building itself, and particularly its great ocular rotunda, whose surprising circular opening literally opens unto the heavens.

Even nestled in a bustling Roman square, before you enter through the great portico and the massive, original, Conan-worthy studded bronze doors, this building speaks its difference, not so much of might or archaic otherness as something almost uncomfortably essential, even basic. One book I skimmed (the City Secrets guidebook, one of the best I’ve even used) spoke of the similarity of its exterior to a child’s drawing of a house: a rectangle surmounted by a triangle, with the third great shape, the circle, implied in the rotunda just behind. Whether it reaches down to the lizard brain or not, the building leaps through the eyes.

Walking inside, I felt as if I was entering a great cave, or a cathedral grove, or a stern angelic palace self-organized from the form constants of the inner eye. Unlike the great mosque in Cordoba, whose hypnotic and abstract regularity was coarsely mutilated by garish Catholic structures following the fall of Muslim Spain, the Pantheon transcends its far earlier Christian overlay. The place was given to Pope Boniface by a Byzantine emperor in 609 AD, and it became one of the first pagan temples to be repurposed as a Christian house of worship.

I don’t even remember what the Christian idols look like because I studiously ignored them, as the peaceful grandeur of the building helped me ignore the packs of fellow tourists who, for the most part, at least kept relatively quiet. (What is the correct collective noun to characterize a group of tourists? My wife and I have come up with other terms: a snarl of punks, a scruff of hippies, a dunkin of cops. A snap of tourists? A menu? A spend? [Mark Pesce has suggested: a gawk] Already tourists are supplanting the old stereotype of Chinese communities. In places like Rome, tourists now also teem.)

There are some beautiful things about the walls of the Pantheon, particularly the use of mirrored slabs of marble to conjure Rorschach blots of patterned stone — a common technique throughout medieval and Renaissance buildings around here, but which takes on a more hallucinogenic character in this pagan place. I would not have noticed without my guidebook, but one corner of the upper level of the circular wall had not been modified in the modern period, and it spoke of a grace and balance that made me want that dang time machine all the more.

But the action of course is all in the rotunda. First there is the pattern of the nested square niches, called coffers, whose ratios and telescoping effect create the vaguely psychedelic sense that they are doors within doors. While the obvious lines are radial and rectilinear, there is also a subtler circular effect of swirling or spiraling created by the shadows cast across the coffers — an effect that only increases the sense of tunneling. This swirling oculus reminds me of Alex Grey’s great painting Dying, but it is perhaps better to think of it as Neoplatonic op-art.

The rotunda also looks like a great eye, with a three-part division of white, iris, and the pupil, with the latter being nothing other than a void that opens into the deep blue air like a James Turrell skyspace. Birds and clouds pass by; rain falls, and sometimes snow they say, though I’m not betting on it this century. But this is not the eye of God, the eye that looks down upon us to judge and condemn. This is not a Christian eye. This is a convex eye, an eye looking up — we are inside this eye, it is ours, staring through the void-lens at the stars our home.