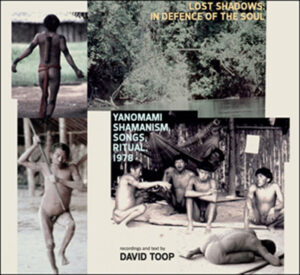

Yanomami Shamanism, Songs, Ritual, 1978

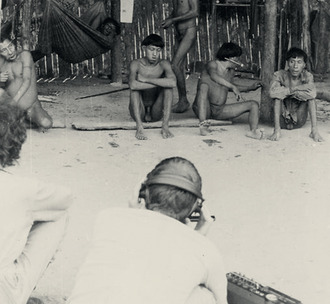

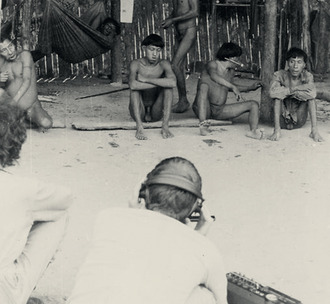

Upon first picking up the new CD release by David Toop, Lost Shadows: In Defense of the Soul, you’re likely to get a pretty good initial idea of what you are in for. “Yanomami Shamanism, Songs, Ritual, 1978” announces the subtitle, and we see photographs of jungles and near naked Indians, wielding staffs and lounging about with those unforgettable Yanomami mop tops, some seemingly under the influence of the powerful hallucinogens favored by the tribe. But though we rightly surmise that we are about to confront some unvarnished ethnographic recordings, we are immediately faced with a choice. Do we first peruse Toop’s long essay? Or do we just dive into the discs?

This choice, long familiar to listeners of studied exotica, goes beyond the privileging of text or sound, language or frequency. Instead, it suggests a basic attitude toward the acoustic encounter with otherness. Progressive global listeners, schooled in the protocols of tolerance and diversity, would no doubt turn to the text first. They would trust such accompanying materials to provide the all-important “context” that, as scholars and other professional browbeaters endlessly remind us, is not only required for an informed understanding of indigenous cultures but also constrains the dangerous operations of fantasy, projection, and misinterpretation. On the other hand, there is what one might call the Sublime Frequencies approach to obscure and unusual ethno sounds. Carving out an almost Vice-like approach to “world music”, the label usually packages its brazen DIY recordings—both audio and video—with little to no background information. The boldness and value of SF’s releases reminds us that the risks of exotica closely abut more liminal and expansive modes of listening. The willingness to dance with the devil of sensationalism can also reflect a healthy distrust of professional mediators, as well as the roving listener’s trust that an imaginatively tuned ear can find intelligence as well as novelty and pleasure in relatively unfiltered sonic encounters.

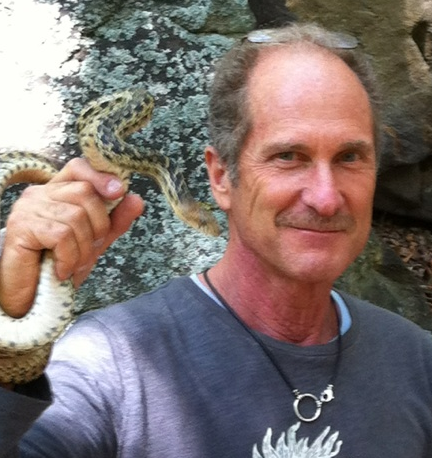

In this case, it doesn’t matter what you choose. In his essay, David Toop offers an informative yet unconventionally expanded fulfillment of the responsible enthnographic mediation of these recordings. In an angular but evocative text that features plenty of the Ballardian lyricism that made Oceans of Sound and Exotica so tantalizing, Toop remixes his personal narrative of the grueling trip through the Venezuelan Amazon with a sprightly sampling of anthropological views and an aesthetic reflection on the marvels and riddles he etched onto some TDK SAs back in the vanishing day. Writing without romanticism but with a restless dissatisfaction with familiar ways of thinking about sound and meaning, Toop gives us some of that necessary context but remains all the while close to the enigmatic opacity of the Yanomami—whose anthropological portraits remain highly controversial—as well as to the absurdity of the ethnographic enterprise. David Toop is particularly balanced in his approach to the “psychodynamic theatre” of shamanic healing which forms the context for many of these tracks. Here he balances a sociological account with an avant-garde sensitivity to that immanent otherworld of spirits wherein “the shamanic specialist must confront and absorb auditory, tactile and visual events of chaos, terror, disgust, wonder, fear, violence and fierce beauty.”

But Toop’s words cannot cushion the tsunami of weirdness that awaits the listener of Lost Shadows, and particularly of the collective shamanic healing rites that open the collection. One of Toop’s attractions to the Yanomami was the culture’s near total absence of musical instruments, which means that what you get to listen to here are human bodies making noise. Moreover, many of these bodies are metabolizing some of the most powerful and bizarre psychedelic compounds in the world: dimethyltriptamines provided by the powdered ebena snuffs that are blown painfully into shamanic (and subsequently very snotty) noses. Like the Putamayo songs that the anthropologist Michael Taussig recorded in the seventies and later released as Yagé Pinta! (Latitude, 2007), the songs and chants the Yanomami shamans do produce seem more about tone and timbre than language. However, David Toop’s recordings capture far more than song or even “voice,” as we confront the psychedelic Yanomami body as a collective multidimensional membrane of vibrating flesh. Alongside the singsong melodies, nasal animal cries, and mantra-like mumbling, we also hear more “universal” sounds: monster growls, hysterical shrieks, juicy sneezes, yawns, barks, upchucks, giggles, tears, Bronx cheers, and a ton of hocked up phlegm. It may help to know that bodily fluids, and especially phlegm, play an outsized role in Amazonian shamanism, but that does not lessen the intensity of hearing crisp recordings of such mythopoeic retching.

This stuff would make Sublime Frequencies proud. And indeed, when these recordings were first released in the early eighties, an Ethnomusicology reviewer complained that, by not focusing on “music”, Toop’s presentation of the Yanomami soundworld verged on sensationalism. David Toop, for whom this mantic mania is anything but sensationalist and the boundaries of “music” anything but fixed, in turn compares the shaman performances to sound poets from the seventies. And we do seem to be in the presence of something both radical and embodied here, something far deeper and more experimental than “song” or “ritual” or “psychedelic experience”. Unlike the Amerindian icaros or mestizo hymns that have become the central sonic tropes within the exploding global ayahausca scene, the Yanomami performances seem resistant to appropriation through the open architecture of their form. Similarly, and in contrast to more familiar modes of Amazonian shamanism, the Yanomami operations are essentially collective, with multiple healers operating in a theatre that combines spectral encounters with casual hanging out, temporary freak-outs with gently mocking laughter.

The second disc provides a bit more in the way of “music,” but here too what comes through most strongly is what Toop has elsewhere called the “growth of form out of social relations.” With the “Wayamou” we hear a rapid vocal exchange between two men that conjures up the verbal acrobatics of auctioneers and black American preachers, while the startling series of young men’s circle songs offers staggered masses of repeated nasal motifs and closely pitched refrains whose joyous cosmic microtones Toop rightly compares to Albert Ayler and Ligetti’s choral works. These resonant modern allusions do nothing to defang the singularity of the Yanomami’s vocal world, however, but instead invite us to challenge the “anthropological” distance that imposes itself between us and some of the more eruptive intensities of human expression you are likely to hear. While David Toop meticulously draws attentions to the constraints and dangers of the ethnographic enterprise, he has too much respect for the outsides of thought and music to keep these sounds inscribed in some preserved ancestral past.