MTT doses the hall with Belioz

I’ve been waiting to hear the Symphonie fantastique live for years, and last night, which happened to be the 177th anniversary of the piece’s first Paris performance, all the waiting was rewarded with a rousing and exquisite throw-down of Berlioz’s total zowie.

Coming in the wake of Beethoven, that idiosyncratic shape-shifter bellowing the way from the classical to the Romantic eras, Berlioz’ 1830 Symphonie fantastique is thoroughly, achingly Romantic, the first tortured, drug-addled, gothic, mystic, ironic, visionary symphony for a century that would become stuffed with dark, tortured, drug-addled, gothic, mystic, ironic and visionary media. At the same time, the symphony comes both early and big in the big romantic turn from taut and confident classical forms towards the messy uncorked spirit, and so has a freshness, mania and impish bravado that reminds me of those mad aesthetes you know in college who, despite all the floppy annoyance of their manner, pulled off their game with undeserved panache.

I’m not really interested in the culture or language of the classical music “scene”, though I am coming to love some of the repertoire (and much outside it). I also like what the cult of the concert hall sometimes brings. I particularly relish the air of conscious attention at concerts, an air that, though often and sometimes deservedly intermittent, I find more taut and pronounced in the symphony hall than the opera. The vibe sometimes reminds me of the meditation hall: many folks sitting very still and drawing their attention toward one point moving and changing through time. When the music and the performance is good, this mind-field feeds back into the music, and the hall can grow sublime, fascinating, insightful, even ritual. And it’s way more fun than staring at a wall, believe you me.

I am no longhair, in the pre-hippy sense of the term. My ears were formed and are still addicted to psychedelia and funk; to perverse power pop and electronic wankery; to bleak and mighty heavy metal; to folk music near and far, with all its sentiments and charms. For ears like this, Berlioz is a blast. For his first great work (I like his Faust too), the young and brash composer squeezed evocative and utterly surprising sounds and textures out of well-trod instruments. All this rich timbre and inventive scoring make the Fantastique deeply pictorial music—it is literally visionary—and this weds well with Berlioz’ explicit intention to make program music—that is, to tell a tale or at least compell an atmospheric scene with the music, rather than rest in the abstract plane so blazingly explored by classical composers like Mozart or Haydn.

The tale in question concerns the now hackneyed figure of a tortured artist, whose obsessive infatuation with some heart-pinging babe is figured in an easily noticeable melody that twists and turns throughout the forty-five minutes or so of music. The first movement was wonderful—and peppered with fascinating pauses that invoke silence in a manner I have not heard in music before then or much since—and the second movement yummy. But then, for the last three movements, the sonic molecules took hold.

Gaian hippies with large hearts for the great outdoors need go no further than the third movement, which invokes the glories of that grand tart Nature. We start out with a shepherd melody on a horn, which is answered in a higher register. Is the echo another shepherd, as the notes have it, or nature herself? The question already came up in “La Pecheur” (The Fisherman), a song from Berlioz’ later stage piece Lélio that was sung with tremendous tenderness by Stanford Olesen during the first half of the program. Berlioz takes the text from Goethe, who writes of a water nymph rising through the waters, who says to her fisherman:

See then your true self

Smiling back at you from the water.

That is the alchemical dream of the nature mystic: to find oneself fused with the awakened thing, now speaking, the dream object, the cosmos that recognizes you in its turn. That’s the dream we hear with the answering reed, a dream that will rise and fall and disappear by the end of the movement, when our hero, after raging with desire and grief at the thought of his love, faces the storm clouds that gather on the horizon, rumbling ominously in a manner your imagination would know even without reading the program.

Fans of martial metal will, like me, thrill to the fourth movement, the “March to the Scaffold,” where our despairing lover gobbles opium and plunges into a visionary nightmare of guilt and judgment that ends with his own death at the guillotine. Berlioz pumped up his crazy march and mocking crowds with big sour thrumping brass, which would have been stanky Gibson SGs run through Marshall stacks if the guy had had them. Towards the close, the infatuation melody returns only to be violently chopped off midway, and the hushed thump-thump-thump in the bass that follows is supposed to be the dude’s hallucinated head bouncing into the basket. Most metal!

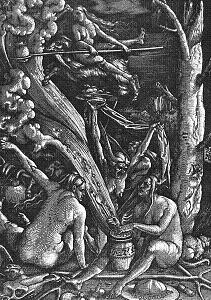

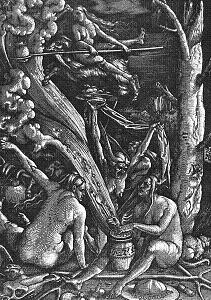

The “Dream of the Witches’ Sabbath” that closes the symphony is fucking madcap, and you can hear Zappa and Goblin and Spike Jones in it. Against rumbling kettle drums and slutty chromatic slides, the melody returns, only now a satanic mockery, “the tune of an ignoble dance, trivial and grotesque” in the original program. In other words, rock’n’roll, but spectral rock’n’roll. Twisted but familiar, it sounds like those thoughts of normal life, usually sweet, that return in the midst of a journey to bait and horrify you with their imprisoning banality. Then our hero’s fantastic crush appears, but now as a gruesome witch who plunges into blasphemous porno cavorting as the bells take up a funeral knell, a grim toll more spine-chilling than those on the first Black Sabbath record, and that, for me, is saying a lot.

Michael Tilson Thomas and crew did a fabulous job with all this. I sensed in Thomas the same affinity to the restless, visionary and richly scored material that he holds for Mahler. The players were all in top form, and no wonder: they were being filmed by weird swooping black robot cameras for the Keeping Score series Thomas does for PBS but that I haven’t seen. The cameras were annoying but I kept my eyes closed to honor the imaginative import of the music out so I didn’t care.

I bet the show’s good though—Thomas is a witty, story-slinging speaker, and I’ve enjoyed all the pre-show talks I’ve seen him give. He is also my kind of San Franciscan. He’s mellow but not shy about being gay, and he was busted for weed, coke and ups back in the 70s, so he clearly likes to have a good time. And though he has achieved pre-eminence in the still rather fuddy-duddy world of American symphonic halls, the guy is genuinely engaged with experimentalism—musical, social, and otherwise—and he does a fine job of communicating that passion to lugheads like me. During the mind-blowing summer Mavericks series of 2000, which was targeted at precisely my demographic, Thomas organized programs of Ives, Terry Riley, Lou Harrison, and Ruth Crawford Seeger (and, yes, Frank Zappa) at a time when the rest of the country was listening to John Williams and Mozart chart-toppers.

That, and concerts like last night, gets MTT a pink thumbs up in the right hand and a thrust of the devil horns in the left.