On October 26 of this year, the psy-trance DJ Goa Gil passed from this earth. I got to meet Gil three decades ago, when I was writing a piece that, while it was an extraordinary blessing to research (especially on someone else’s dime), proved a mighty pain in the ass to get into print. I first heard about the psychedelic rave scene in the Indian state of Goa from the guys in the techno act Orbital, who were very nice blokes. In those days I had a contract with Details magazine and convinced the editor-in-chief, a smart fellow named John Leland, to send me there for a feature. By the time I returned to the States and wrote up the piece, Leland was gone. Over the next few months, the new guy, who I dubbed Mr. Hollywood, demanded an ungodly number of rewrites and then killed the piece anyway.

A version of the thing wound up running in Option in 1995, under the name “Sampling Paradise.” By then the prose had been kinda beat down by all the processing, and many meatier topics left untouched. I later reworked the article into a more scholarly (specifically Deleuzian) article that appeared as “Hedonic Tantra” in an academic collection on rave and religion edited by my good friend Graham St. John. What follows are sections from the original article that feature Gil. The whole “Sampling Paradise” article, which contains a rare interview with Laurent, one of the originators of the Goan sound, can be accessed here.

Gil was happy to get himself out there, and since my interview, his story has been told many times (this French piece in Trax is particularly fine, and contains many rare and wonderful photos). I never hung out with Gil again. Though I have tried to catch the psy-trance vibe many times, and had some genuine ecstatic experiences, I remain lukewarm on the genre (more or less evolved from Goa trance) so tended to skip parties were Gil played. But I admired him from afar. As a DJ, Gil never wavered from his commitment to a particularly heavy, hardcore, and dark subcurrent of psy-trance. It would have been very easy for him to relax into a happy hippie vibe but instead he kept the brutal cosmic ferocity high. No doubt many brains were scrambled along the way, but I trust that Gil kept some cosmic love in the mix.

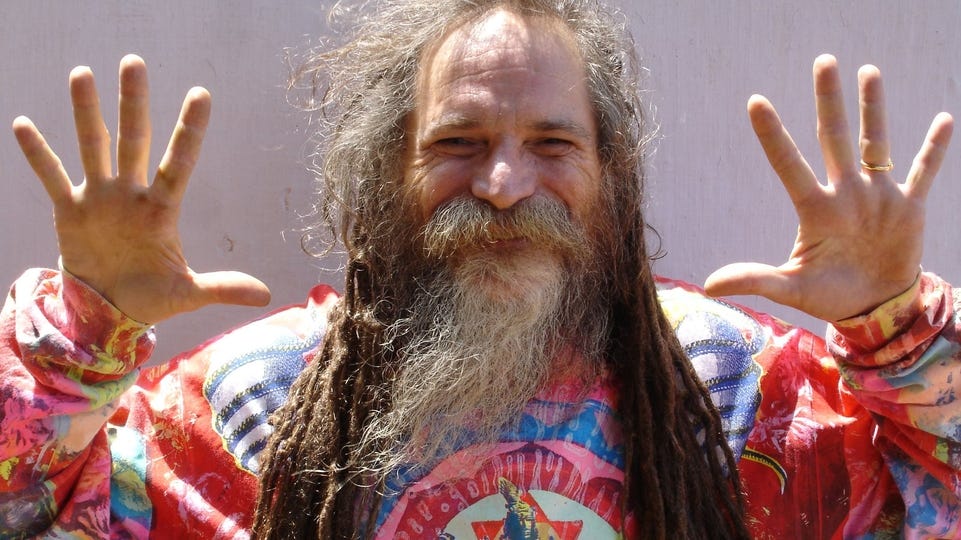

It’s one hour past midnight, and the jungle throbs with techno. The tropical breeze off the Arabian Sea is warm and wet. I stuff a wad of rupees into the outstretched palm of the auto-rickshaw taxi-driver, and head toward the noise. I’m 350 kilometers south of Bombay, in India’s coastal state of Goa, and I’m about to hit a rave.

The forest clearing swarms with bohemian backpackers and European hipsters strutting their cyberdelic stuff: holographic sneakers, flared fractal jeans, floppy Dr. Seuss hats stitched with the mirrored cloth of Rajasthan. The freaks gyrate around junky speaker stacks, soaking up the interstellar trance beats like they earlier soaked up the sun. A lithe Japanese girl dances by with a glowing plastic jewel affixed to her third eye, giving me and everyone else she encounters an omnivorous grin. An old Indian beggar passes through the crowd, the black lights turning his turban the color of moonlit bone.

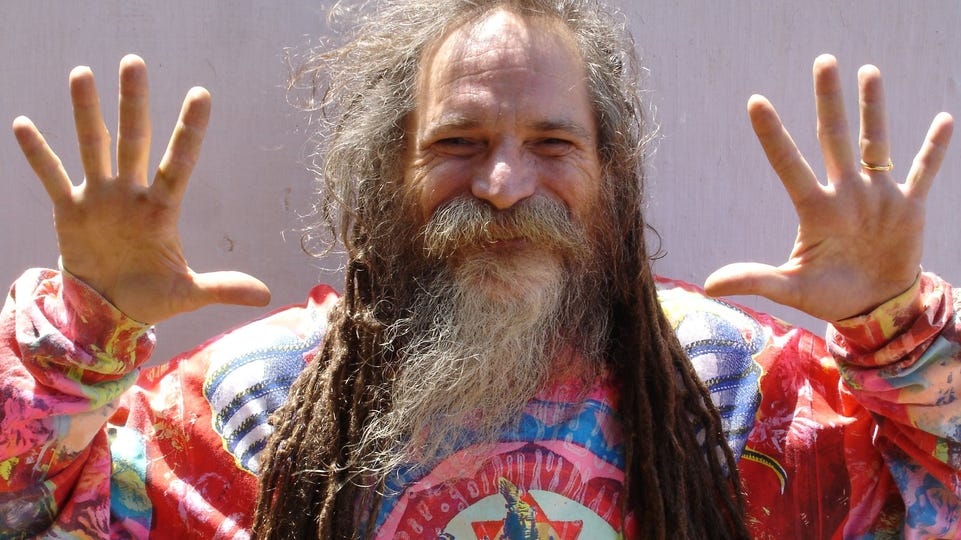

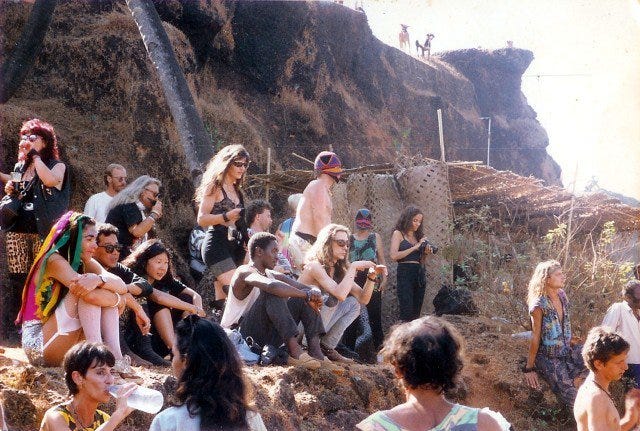

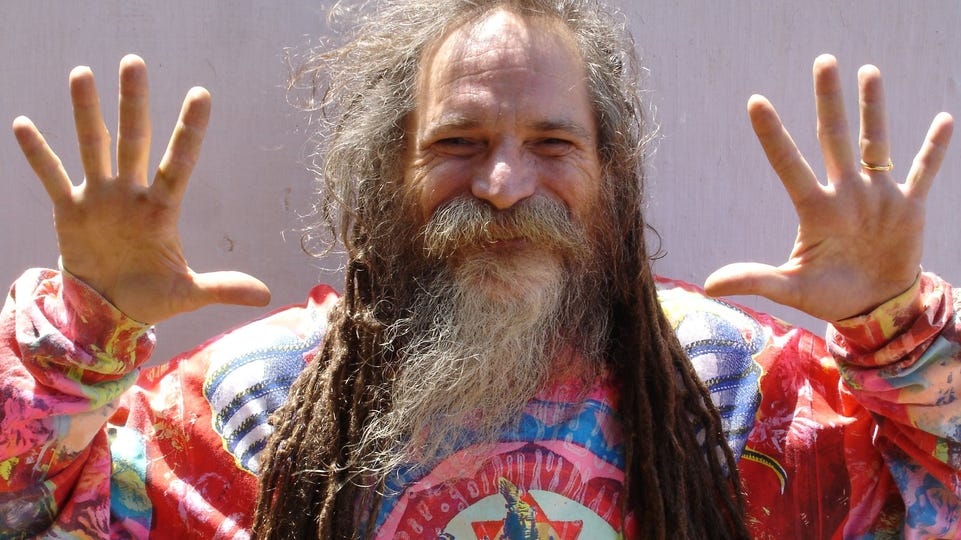

The DJ booth lies at the edge of the clearing, set beneath low-hanging trees and cordoned off with bamboo. A large middle-aged hippie with white-boy dreads and a bearded, sun-burnt face stands behind the mixing table, pushing buttons and slapping DATs into two small decks wired through a pint-size mixer powered by a generator hidden in the bushes behind. Alongside stacks of black-matte cassettes stands a candle, a smoldering stick of incense, and a small devotional portrait of the Hindu yogi Shiva Shankar, sitting in the half-lotus position on a tiger skin.

“That’s Gil,” says one of the Indian locals mobbing the techno-shrine. “He’s one of the best.”

I had already heard about Gil from Genesis P. Orridge, who had filled me in earlier on the technofreak legacy of late-60s London clubs like Middle Earth and UFO. “The basic premise was smoke and light shows, large quantities of ecstatic chemicals, and dancing like a dervish to accentuate your artificially-induced mental state to a point that was equal to and integrated with an ecstatic religious state.” When the scene decayed, the heaviest psychedelic warriors split, taking their musical alchemy with them. Some went to the Spanish island of Ibiza, while the more esoteric heads went east. Though Gil was from San Francisco, he had trod a similar path. “You have to find him”, Genesis told me. “He’s one of the links.”

But Gil is too lost in his craft to talk, and I merge back into pulsing psychedelic bardo of the dancefloor. I’ve never seen people move like this: at the edge of their bodies, ceaselessly flowing, like Deadheads bonedancing in overdrive. Disembodied vocal samples float through the air like ghosts, triggering mindfucks left and right: “There are doors.” “The last generation.” “Everybody online?”

Craving touch-down, I head for Goa’s gypsy version of a chill-out room. In an adjacent field, local village women have laid out rows of straw mats and piled them high with fruit and cigarettes and bubbling pots of chai (tea). Scores of freaks flop out on the mats, smoking copiously by the light of kerosene lamps and sipping syrupy brew from scalding glasses.

I plop down next to a crowd of Brits. Pete is in pajama pants and an open vest, his aristocratic Tory features oddly framed by long scraggly hair. Hunched next to him is Steve, a skinny blond twentysomething rolling a spliff.

“Have you seen The Time Machine?” Steve asks me. “There’s this noise that the Morlocks use to call the Eloi underground. That’s exactly how it was five years ago when my friends and I first came to Goa. We heard this booming rhythm in the distance. We didn’t know where the fuck we were, but we just crashed through the jungle with our torches. The sound was calling us. I got real paranoid that there was some alien intelligence directing the computers, like the Morlocks, summoning us to a place where they were gonna eat our souls.”

Pete nods as if nothing his friend says could surprise him. “My first party, I just got the feeling I was in some spiritual Jane Fonda gymnasium,” he says. “Boom, boom, boom, and everyone going into trance. It was quite alienating actually.”

“I just get a feeling of conspiracies, mass conspiracies, huge conspiracies,” Steve counters, passing me the spliff. “We’re under some bigger control at this point, and there’s a lot more going on than we know.” When the smoke hits my brain, I can almost see the plots thicken. I ask him how Goa differs from the raves in England. “Here people know about the history of freakdom, of free-form living. That vibe is carried forward with the music. In England it’s not really freaky anymore. It’s too organized. People are wearing the right kind of T-shirts, whereas here people will rip their T-shirts apart and run down the beach.”

As the early sunlight streaks the sky, I leave the duo and head back to the dancefloor. Dawn is Goa’s sweetest moment. The bpms slow, and the night’s bracing attack gives way to a smoother, narcotic trance. According to Goa’s more shamanic DJs, the change of pace has a ritual function: after “destroying the ego” with the night’s hardcore sounds, “morning music” fills the void with light.

The dawn light floats through the clearing like incense, and a deep resonating chant emerges on top of the lush, succulent beats: “Om Namah Shivaya.” It’s a mantra devoted to Shiva, the Hindu god of tantric transformation and hence something of a freak favorite. Slowly, a Benetton ad’s worth of folks emerge

from the gloom: Australians, Italians, Indians; Africans in designer sweatshirts, Japanese in kimonos, Israelis in polka-dot overalls. A crowd of old-time Goan hippies ring the clearing, grey-haired and beaded creatures who dragged themselves out of bed just to taste this moment. As the dust fills my nostrils, I wonder whether Goa’s raves were much more than digitally remastered Be-Ins. Maybe something far more strange and ancient than beatnik dreams of the East was entrancing this crowd, something these old-timers knew but would not say. One thing was sure: Goa’s underground was deep, and I was sinking.[…]

Goa is only one stop on the hippy trail that three decades of drop-outs, drug lovers and mystical travelers have carved into the East. But Goa is perhaps the only boho roost where techno is as ubiquitous as faded blue jeans. The digital beats seep out of half the houses and all the cafes, morning, noon and night. In three weeks time, I heard Pink Floyd once. I did not see one acoustic guitar.

For a certain underground breed of DJ, Goa is an esoteric Mecca, and they flock from every corner of the globe—New Zealand, Japan, Israel, Italy, France. Established music-makers arrive with their fall crop of trance tracks for exchange and tasting, while rising stars train like athletes and perform more for their fellow DJs than the crowd. The Orb’s Alex Patterson has passed through, the famed London remixer Youth is a regular, and Sven Väth—Frankfurt’s techno Kaiser—fell in love with the place.

[..]

DJs are the maestros of the information age, and not just because the discs they spin are basically digital creations. Freed from the gravity of faces and fixed names, underground dance music finds its essence in constant mutation and total overproduction. Sifting through hundreds of records a week, DJs define themselves in part by what they comb out of the data overload. That’s why many act like spies, taping over record labels, or buying all available copies of a favorite record and destroying all but one. DJs are made of information. But in Goa, where the inability to mix makes selection particularly important, they drop their guard and swap tapes.

A few of those tapes are brewed locally. Johan is a young German producer who looks like Anthony Kiedis with a brain. He lives in a huge house in a small inland village, his room containing little more than a bed, a bhatik print and his gear: Macintosh PowerBook, Akai sampler, keyboard, DAT deck. I’d heard two of Johan’s intense tracks on the Dragonfly label’s Project II Trance (under the name Mandra Gora), which along with Juno Reactor’s Transmissions and the Ethnotechno and Concept in Dance compilations, is the best stateside introduction to Goan trance. But Johan doesn’t like to DJ—he’s one of those hardcore power dancers who treat the night as one long track. “With a combination of good music, a good spot and good dancing, it’s like a cosmic trigger goes off,” he says of Goa’s greatest rites. After a night of cosmic gyration, Johan would return to his studio, download his vibes, dump the bytes onto DAT, and slap the tape onto his DJ friends. “It was like a perfect feedback loop.”

When Johan first arrived in Goa six years ago, the techno-trance scene was totally off the map. Synchronicities abounded. “It was like a poker game no-one could follow.” But these days he’s starting to sell his stuff in the West, and though he plans on setting up a large Goa studio as soon as he can figure out the right bureaucrat to bribe, he’s pessimistic about the future of the East’s nomadic underground. “Soon we’ll have a global digital network where everyone will know where everybody is all the time.” He looks me in the eye as only a German can. “What you’re here to write about is already dead and gone.”

Väth and Johan are friendly enough guys, but many Shore Bar insiders set themselves apart from the rave tourists (and journalists) with the same kind of snobbery you find in London or New York. Given the mystical legacy of freak India, the cliques here have a mystical air, like they’re pushing the envelope of consciousness itself. As Raja Ram, an old moustached prog rocker-cum-techno musician, told me, “You have to become a neuro-naut to understand this music. We’ve gone from flint-rock to the moonlanding in a few thousand years, and now we’re on the edge of the world opened up with information machines. This is a new inner space we’re exploring.”

[…]

One DJ I did manage to nail down was Gil, the dread-headed Kris Kringle who spun at the hilltop party. When he DJs in San Francisco and other Western cities during the summer monsoon, he’s known as Goa Gil—only one of the items that makes Gil less than well-loved by today’s younger DJs. Gil lives in a spacious brick house behind the Orange Boom restaurant and alongside a pile of rubble he calls a temple. “Come in, come in,” he barks before I even introduce myself. A large collage of rave flyers, psychedelic posters and photos of Hindu holy men covers one wall.

Just as I start to get comfortable, Gil’s pretty young French wife Ariane—herself the child of Goan freaks—begins interrogating me. “Why are you writing an article for? You’re going to spoil everything.” She complains about a piece in iD magazine that resulted in floods of Brits. “Now we get the Americans and all the hip-hoppers coming,” she whined. I assure her that the hip-hoppers have other things on their mind. She grabs her sunglasses, and storms off to the beach.

But Gil knows he has a story to tell, so he tells it. Growing up in Marin County in the ’60s, Gil took the bus down to the Haight after school. He fell in with Family Dog, the loose freak collective who sparked the psychedelic concert scene before Bill Graham moved in with dollar signs in his eyes. In 69, fed up with “rip-offs and junkies and speed freaks,” Gil bought a one-way ticket to Amsterdam. He then made his way overland to India, where, among other things, he discovered the sadhus.

Hymns in the ancient Vedas describe these wandering holy men as longhaired sages who lived off the forest, covered themselves with ash and drank the elixir of the gods. Today, some of India’s hundreds of thousands of sadhus are strict ascetics, some are simply beggars, and some resemble Hindu Rastafarians. These impressive, bloodshot souls wander about, wearing their hair in long dreads and finding spiritual sustenance in charas, India’s yummy mountain hash. Before they smoke the clay pipes called chillum, the sadhus cry

out “Bum Shiva!” the way Rastas bark “Jah!”

Not surprisingly, the freaks took to the sadhus. Gil went whole hog, living in caves, wearing orange robes, and coaxing the Kundalini up his spine. But he still found his way to Goa’s firelit drum circles every winter. Despite persistent false rumors that the Who or the Stones or the Beatles left their gear on the sands of Calangute, the source of Goa’s music machines was a fellow named Alan Zion, who smuggled in a Fender PA and two tape decks overland.

According to Gil, these parties are the direct ancestors of raves. Techno historians already know that English working-class kids brought raves back from Ibiza, the cheap vacation island off of Spain whose weather, slack and lack of extradition treaties made it a Goa-style hippy colony decades ago. While many DJs shuttled between Ibizan summers and Goan winters, some claim that the more authentic lineage of electronic ecstasy belonged to the East. As Genesis P. Orridge put it, “The music from Ibiza was more horny disco, while Goa was more psychedelic and tribal. In Goa, the music was the facilitator of devotional experience. It was just functional, just to make that other state happen.”

And Goa went totally electronic in 1983, when two French DJs named Fred and Laurent got sick of rock music and reggae. At the same time Derrick May and Juan Atkins created the futuristic disco-funk called “techno”, Fred and Laurent used far more primitive techtwo cassette decksto create a schizo’s brew out of New Wave, electronic rock, gay Eurodisco and experimental industrial bands like Cabaret Voltaire and the Residents. They slipped electro-pop like New Order and Blanc Mange into the mix, but only after cutting out all the vocals. It was heady shit, and soon hipsters started slipping them underground tapes from the West.

Gil and his friend Swiss Ruedi quickly joined in, but the techno transition was not smooth. The freaks were attached to their Bob Marley, their Santana, their Stones. Ruedi had to enlist a bodyguard to ward off some rock fan’s blows.

“How can you listen to the same music for 15 years?” Gil now booms. “I used to love the Dead when I was growing up, but I can’t listen to that stuff anymore. It sounds like cowboy music.” Gil thinks that music is always flowering, but that the juice moves through different genres, always one step ahead of the record companies. “Now it’s in techno. Music has gone through a complete cycle. It started in ancient times with tribal drumming, and now it’s come back to tribal trance techno. Where do you go from there?”

Gil starts pacing about, wildly gesticulating. “I’m basically just using this whole party situation as a medium to do magic, to remake the tribal pagan ritual for the 21st century. It’s not just a disco under the coconut trees.” He pauses to light up a Dunhill. “It’s an initiation.”

Gil slaps on two remixes he made while visiting San Francisco. The band is Kode IV, a German duo who brag about producing tracks in five minutes and which Gil was to join later in the year after one of the members died. He blasts the tunes, and towers over me as he identifies the samples: a sadhu’s “Bum!”, the Pope, Aleister Crowley. Then he plays the “Anjuna” remix of the cut “Accelerate,” towering over me as he repeats word for word a long sample cribbed from some flying saucer movie: “‘People of the earth, attention’,” he booms over the beat. His eyes bore into mine, and for a moment I feel like he’s channelling the message to me directly from the aliens, like I’m finally getting the key to Goa’s surreal scene. “‘This is a voice speaking to you from thousands of miles beyond your planet. This could be the beginning of the end of the human race.'”

Ariane walks in, breaks the spell and bad vibes me out of the house. Gil follows me outside, trying to explain the reasons for her underground protectionism: the rising pollution, the clueless young DJs, the sharp rise in

prices. Gil shakes his head. “We came here so long ago, to the end of a dirt road and a deserted beach. It was like the end of the world. And now the whole world is at our doorstep. The communications lines are open. Where do we go from here?”

If Gil had listened a little harder to the music he loves to spin, he would have seen it all coming, because techno is the sound of one world shrinking. The media tsunami that gave backwater hippies like him DAT players and computerized music has also brought fax machines and MTV and journalists to their hideaway. Gil’s stuck in the paradox of the technofreak: you can’t drop out and plug in at the same time. The underground is now networked, and you can’t escape the feedback loop for long. You might even call it karma. […]

Read the whole puppy.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. These pieces and updates come when they do, and I dodge the stress of the hamster wheel by not offering paid subscriptions. If you want to support me, you can subscribe, share the post, or drop a monetized appreciation in my Tip Jar.