The Apollonian Shimmer of the Beach Boys

When I was boogie-boarding the Del Mar waves in the mid-’70s, I remember hearing this surf tune that name-dropped my hometown and thinking, cool, we’re on the map, right along with “Hollywood” and “Disneyland” and “Chico.” But the Beach Boys sounded pretty dinky to my Led ears, and the images that crusted the band like barnacles—Sunkist soda, bearded burnouts, state fairs, longboards—were too lame to hook me much. And the canons of AOR, new wave, and indie rock didn’t teach me any different. But this summer, in a sudden encounter with the soul of Brian Wilson, I became a stone-cold Beach Boys freak. Blame it on Capitol and Epic’s CD reissues, on the cool tribute record Smiles, Vibes & Harmony, on Paul Quarrington’s novel Whale Music, on this California Barbie I got with a Brian flexie-disc inside, on Dominic Priore and David Leaf, the fan-nuts whose respective Look! Listen! Vibrate! SMILE! and The Beach Boys broke down whatever objectivity I had left after weeks of air-organ and dance, moist eyes and smiles. Whatever it was, my neighbors rue the day.

Right off the bat it must be said that Capitol has burned rubber with these CD reissues. Though they should have released everything in mono, the sound is magnificent, and the hour-plus, data-packed “two-fers” these suckers come packaged in are a consumer’s paradise (Leaf’s liner notes alone will make a Brian disciple out of you). For once, bonus tracks are actually bonuses, from the lewd “All Dressed Up for School” to the rich Pet Sounds instrumental “Trombone Dixie” to an alternate take of “Heroes and Villains” that includes the joyous and legendary “in the cantina” section. Collect ’em all.

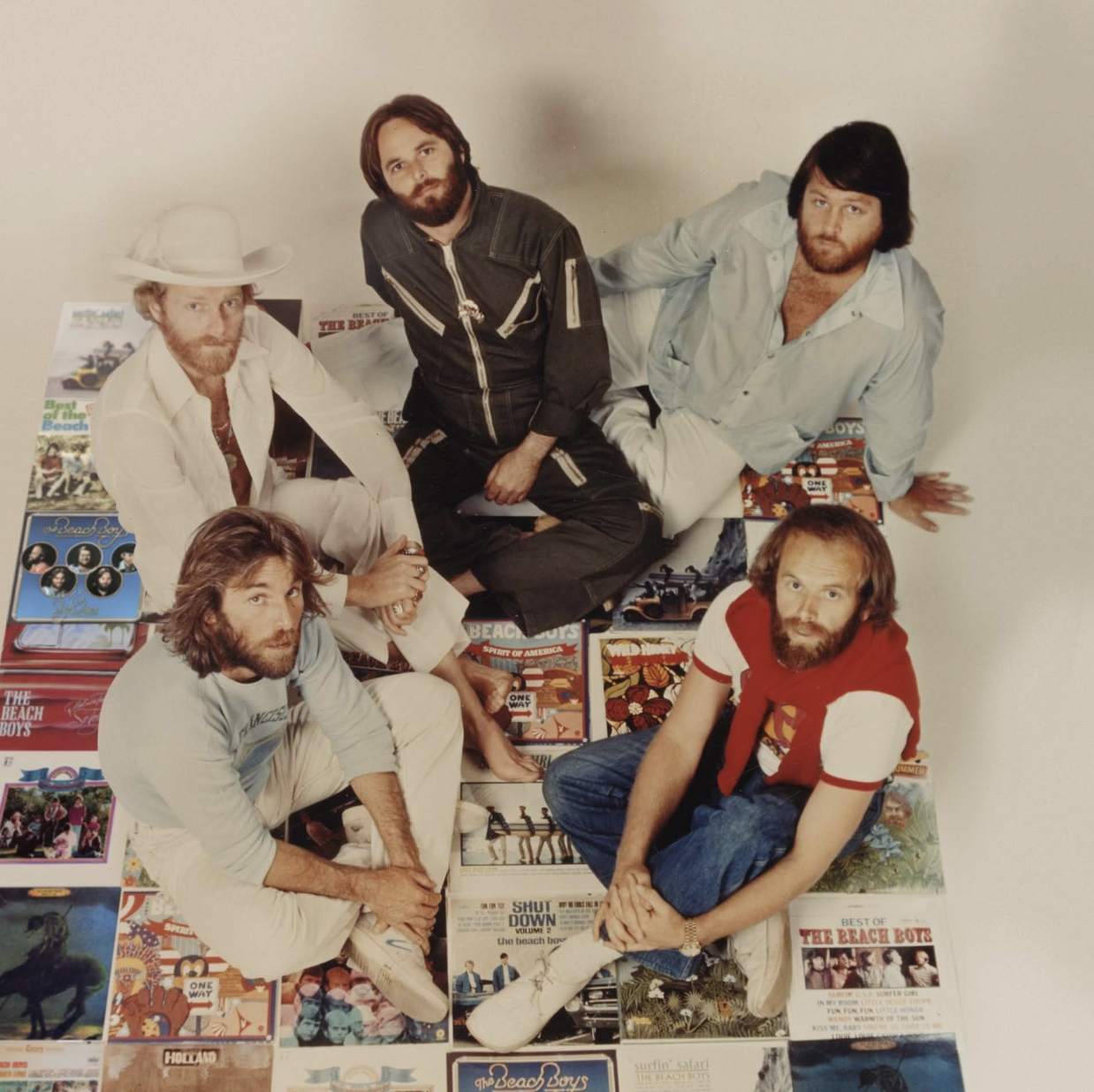

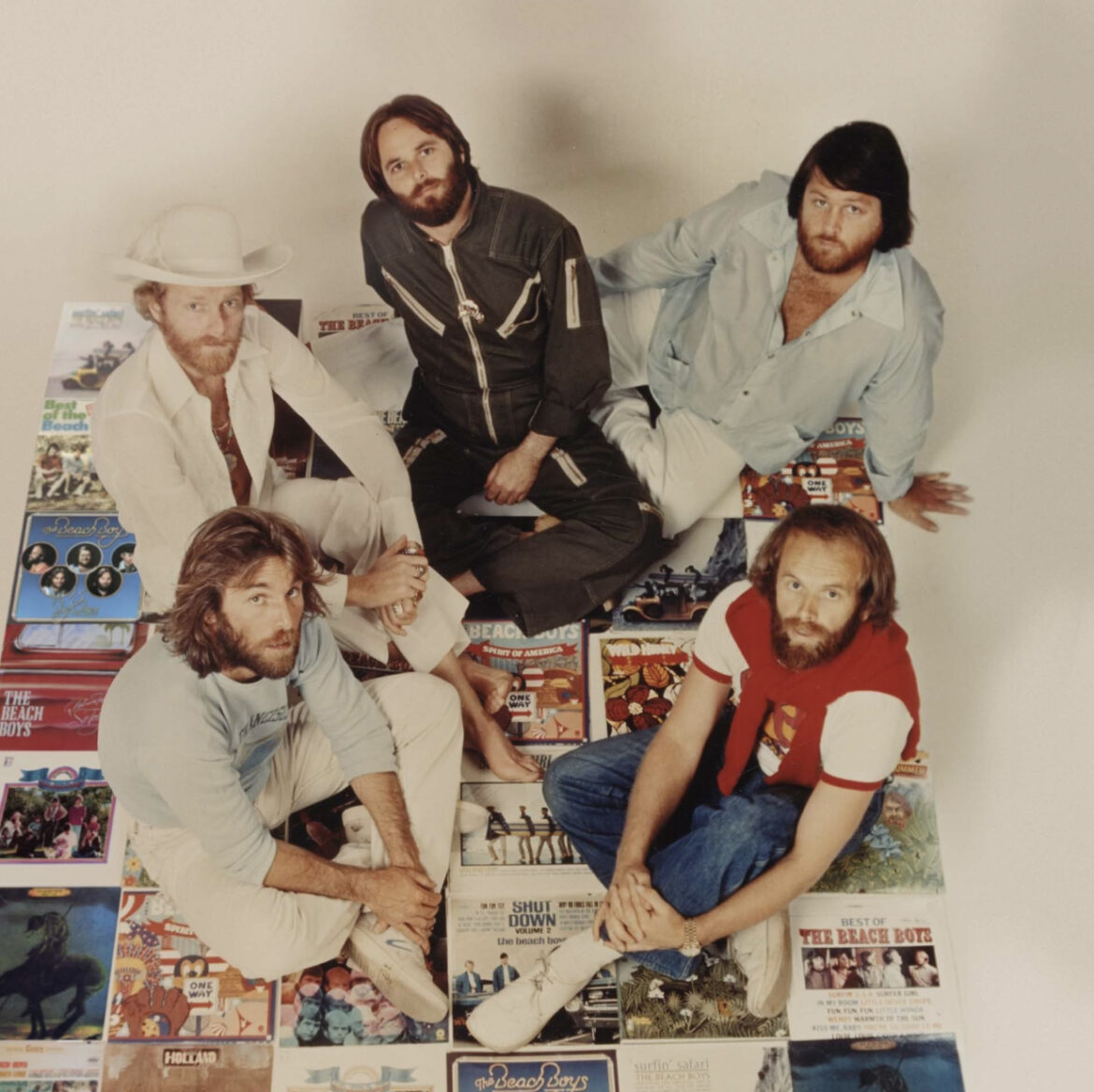

Then again, why bother? Nowadays the Beach Boys are either dead, deranged, or dinosaurs; their records are Eurocentric, square, unsampled; they’ve made too much money to merit hip revisionism. Besides, you know the hits by heart. Though the stuff is superficially amusing, and seems to spontaneously generate nostalgia, these obvious virtues remain fairly blasé. But the pleasures here aren’t solely for the kitsch cultist or the aged. The story this stack o’ discs tells is as endless and full as a summer of innocence and experience. Though he stands aside Phil Spector and Harry Partch as a grand American musical eccentric, Brian luckily didn’t shut himself off from his era until after he had fallen into its darkest maw. So his band’s music sketches the mythopoetic becoming of California itself, from surfing to cruising to God to terminal mellowness.

Myths the size of California elect their own pantheons. Ours has Ronald Reagan and Charles Manson at either end, and the Beach Boys may be the only bridge between those deranged poles. There is a wider range of political and aesthetic sentiments in their records than in any other band in those heady times—like the state, they expand and bloat and contradict themselves. But the Beach Boys don’t just mirror these contradictions (speed/sloth, Bay Area/SoCal, utopian/reactionary, mass cult/esoterica), they actually seem to work some of them out as well, succeeding about as often as they fail. I don’t love this band for what they represent but for how scrambled and strange they made those representations, how much brilliance and scary emotion lurk beneath those simple images of fun.

Of course, none of this would be half as powerful if the music didn’t itself catch a wave and ride it all the way to shore. These records document a development rare in pop: music that becomes less commercial as it grows, until the brakes are put on and it swerves into something else entirely. Born from a simple graft of collegiate harmonies and primitive garage rock, Brian’s musical career swells into fluttering rhythms and astral choirs, dense “pocket symphonies” that in a few months settle down into a resigned and mellow embrace of the all-too-human limits of pop. Not only did the Beach Boys write a soundtrack to the early ’60s, but Brian let loose a delicate and joyful art-pop unique in music history and presaged the mellowness so fundamental to ’70s California pop. The arc of this music sounds, in some strange and fundamental way, alive, a rainbow that rises and falls on the sand.

***

Emerging out of the suburban ’50s, the Beach Boys—four squares, one greaser (Dennis)—dug beneath the concrete of Hawthorne and struck a gold mine of pop myth-marketing: the beach as teen utopia. Driven by the Wilson brothers’ hard-assed one-eyed huckster dad Murray, the Boys almost immediately achieved a momentum of illusion (only Dennis surfed) matched solely by Hollywood and Disney, a momentum that yanked pop fans into California’s expanding, concrete heart. Long before Jonathan Richman, they had the dinky nailed down. Tunes like “Fun, Fun, Fun,” “I Get Around” and “Help Me Rhonda” buzz like roller-coaster rides: they start off simple, even predictable, but then weird chords come out of nowhere like quick turns, and those massed harmonies carry you towards the pinnacle, that moment you’re in heaven, holy and smiling and about to fall.

It’s on the second side of The Beach Boys Today! and some of Summer Days (and Summer Nights) that you first sense Brian Wilson as a producer/composer more than a Beach Boy. The studio became Brian’s sandbox, where he would breed complexity, telling the Boys and baffled studio musicians to plant seeds that would bloom only in the final mix-down. But he was always more heart than high-brow, and he’d listen to his gems on a tinny studio speaker to make sure they’d sound good on a car radio. He changed keys, voicings, and tempos for the same reason you shift gears: to move with grace and fun. So the delicate opening bars of “California Girls” draw you into a dance in a king’s court where, as the key shifts downward, you notice orange bikinis peeking through the ladies’ finery, and then that dopey carnival organ starts up and everybody’s stripping and drinkin’ beers in the sun, the harmonies are glistening like chrome, and the body is loaded with the fullness of time.

But by engineering the happy vibes of the Beach Boys’ greatest hits, Brian was already outside their plenitude, and this distance began to seep into his musical voice—on “I Get Around”, he was already singing “I’m getting bugged driving up and down the same old strip.” The pressure to keep topping himself pushed him over the edge: he lost it mid-flight, cried on his mom’s shoulder and, by Today, had given up touring. Pet Sounds is the sound of Brian finally parking his T-Bird in the garage, grabbing a bag full of hash brownies and sugar-cubes, and going inside. It’s the perfect era: the Beatles released Rubber Soul, and hair’s getting long but doesn’t have any fucking flowers in it yet. So the interiority of Pet Sounds isn’t, “like, heavy,” but pure Brain Wilson land, full of wood and wind and naive plaints. The finest melancholy is about relishing lack and the tug of time, and Brain captures those delicate, golden-hued spaces between self and the world. Pet Sounds emanates devotion without dogma, because God only knows whether love is here or gone, if life begins with a wish (“Wouldn’t It Be Nice”) and ends with a “No.” Either way, if you listen to Pet Sounds the way Brian listened to Phil Spector’s “Be My Baby” (over and over and over), you’ll know that Brian touched the hem of God, and found it textured.

Not that he wasn’t reaching for another sonic cookie all the while, like silverware or accordions or plucked piano strings or barking dogs or plastic water jugs or bicycle bells or a Theremin copped from Hammer films. This sense of worlds squeezed into minutes reaches is apex in “Good Vibrations,” the “teenage symphony to God” Brian slaved over for months after Pet Sounds. “Good Vibrations” is the sound of the cusp, the sound of a pulsing cello, a vision not about the trip but about coming on, that succulent ephemeral moment of dawn. And it’s not dated because the dawn is never dated. Give me a better woman-as-truth-as-acid line than “I don’t know where/But she sends me there” and I’ll buy you a health food store. Beam “Good Vibrations” to the cosmos, and the aliens would sing back.

After “Good Vibrations,” the bands’ power dropped while Brian kept getting higher. The wave broke, and Brian’s next masterwork became the best rock record never released. Smile was to be his “Rhapsody in Day-Glo,” a collage of elemental spirits, oddball instrumentation, and Van Dyke Parks’ American Gothic verbiage. But Brian the Gemini had opened too many doorshe thought that only his pool was safe from electronic bugs, that his music was going to set L.A. on fire, that Phil Spector had hired “Mind Gangsters” to get him. Surrounded by negative vibes of his and others’ creation, with Parks away making the brilliant, recently reissued Song Cycle, Brian bagged Smile by mid-’67. And while a lot of shrapnel punctures later Capitol albums (much of Smiley Smile, “A Prayer” and the great “Cabinessence” from 20/20, even the muted “Child is the Father” horns in Dennis’ “Little Bird”), Smile remains an enigma of epic proportions, encouraging generations of collectors to hoard Brian arcana like shards of a grail. For a deep draught of this pop cult vibe, check out Priore’s book Look Listen Vibrate SMILE!, an exhaustive collection of articles, rhapsodies and information that pulls you (or me, anyway) into the strange undertow of Beach Boys fanaticism, an undertow partially conjured by Brian’s own elusive schizophrenia.

***

The Summer of Love had other joys in store for our heroes. The San Fran-centric counterculture rejected the Beach Boys, and while hipster slams—Jann Wenner’s in particular—were tin-eared and snotty, they weren’t entirely unfounded. This was a band who contained in Al Jardine a guy so bland as to elicit no screams on Concert, to appear clean-shaven even with a full beard, whose worst tour addictions were to long-distance phone calls, and who entered manhood wanting to be a dentist. Or take Mike Love, the front-man who later turned the band into nostalgia merchants before their time, and whose white robes belied his Vegas temperament (not that he didn’t spend six months in the Alps learning how to levitate with the Maharishi a full ten years after the Beatles bagged the creep). The Beach Boys were always as much Orange County as Big Sur. Their sound was so white as to be translucent—”Surfin’s U.S.A.”‘s rip of “Sweet Little 16” aside, Brian Wilson was more about the Four Freshman than Chuck Berry—and the “purity” of tone and genetic proximity that smoothed their voices was almost creepy, pseudo-castrato, a “barbershop” sound that Hendrix, on “Third Stone From the Sun,” went thumbs down on.

But Brian’s god was not Jimi’s. Hendrix got down in blood and jiz and the Dionysian feedback of rebirth, a far cry from the Apollonian shimmer of the Beach Boys. If there was a battle pitched, Dionysus won. Just listen to the shift in LA’s other brilliant Burt Bacharach fan, Love’s Arthur Lee, whose Forever Changes is the only 60s pop-art slab that gives Pet Sounds a run for the money (mention Sgt. Pepper’s and I puke). By 1968, Lee lost it to fuzz and wank.

Dislodged by hippies, the Beach Boys didn’t slide into raunch and exoticism (Smile had banjos, not sitars), but into the arms of the mellow. The bearded pale-face R&B of ’67’s Wild Honey presaged the ’70s and beat out the “honesty” of Dylan’s John Wesley Harding in one stroke. As on Friends and 20/20, the scale was beautifully human, and their old plenitude popped up as it does in life: in fragments. You can hear this in Friends’ “Be Here in the Morning:” when they come to the word “full” in the line “you make my life full,” the laid-back music drops out and the Boys burst into manifold, a cappella splendor. But their crystalline spurt spends itself in seconds, and then you’re just sipping beers at sunset. And though they’d begin the ’70s with a comeback tour, a new label and a masterwork (Sunflower, recently reissued along with ’71’s Surf’s Up and ’72’s Holland), the decade slurped them down fast.

Dennis Wilson was the one Beach Boy destined to drink the era to the dregs. Like so much in this story, his substance-ravaged end was fitting, as Dennis was the Beach Boys that experienced, while Brian brooded and tinkered and Mike showed off. Dennis rounded out the Beach Boys as a band: a thrasher, a surfer, a true hunk, a red-blooded partier whose hedonism was deep and genuine enough to lace his greatest songs with the melancholy of the body he so abused. He immersed himself in the high life with open arms and an uncomplicated smile. I mean, this is a guy who let Charles Manson and his family live in his house for weeks in 1968, jamming with Manson and calling him his “wizard” (20/20 contains a hypnotic space-pop tune of Dennis’ called “Never Learn Not To Love” that was actually written by Charlie—knowing this, the lyrics “cease to exist/come and say you love me” seem sinister enough to earn Dennis a room in Hotel California). And Manson wasn’t the only creepy-crawly Californian who marked the drummer’s ravaged adult life. When Dennis drowned in 1983, his wife Shawn Love, reportedly Mike’s illegitimate child (it just doesn’t stop, does it?), wanted him buried at sea. It was only by appealing directly to King CA, Ronald Reagan, that she was allowed to slip Dennis’ booze-bloated body into the waters. Sure, the myth is not the man, but Dennis had it tattooed on his loins.

***

While Dennis’ talent was growing in the late ’60s (“Little Bird,” “Be With Me,” the bonus track “Celebrate the News”) and blooming on Sunflower, his big brother was being sucked into the vegetable core of the decade at the door. After writing show-n-tell songs like Friends‘ “Busy Doin’ Nothin” and 20/20‘s “I Went to Sleep,” Brian seemed to be going all the way back to ’63’s “In My Room” when he holed up in a Bel-Air bed, with only the angels carved in his headboard to look over him as he whacked off and gobbled drugs like candy. Not that he lost the touch: “Til I Die,” from Surf’s Up, is a realized dream of clouds and deep chasms, and features the band’s best use of the vocal round ever.

The ’70s Brian is such an evocative figure—careless, obese, beatific—that only an unfettered imagination could do the image justice, and Paul Quarrington’s roman a clef novel Whale Music does it. Starring Desmond Howell of the Howell Bros., the holy man Babboo Nass Fazoo, and Claire from the planet Toronto, Whale Music is a sad and chuckling stream of druggy consciousness that spills from the damaged mind of Desmond, who uses constellations to navigate his house in a quest for pot, who reminisces about “bee-jays” and his dead brother Danny, who writes music for whales. The highest complement you can pay this irreverent work is that it’s as funny as Brian himself—a man who revealed his secret TM mantra on a talk-show, and who answered a fan mag question about surfing by saying that it’s “a very challenging sport. I’ve never been able to meet the challenge.”

Unfortunately, Brian is still roped to the dark absurdity of California. “Dr.” Eugene Landy, L.A. therapist, pulled Brian out of bed and never let go of the reins. Another classic Californian, Landy himself is an evil parody of the kind of psycho-fascism—like TM and EST—that most of Brian’s band bought hands down. Brian’s fragility may underlie the enormous sensitivity of his music, but it also left him defenseless. Brian Wilson never grew up and the world ate him. Whether ominously counting the years in “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man),” crying on his mother’s shoulder, or making session violinists wear plastic fire helmets, Brian Wilson is the child that is the father to the man. There’s one moment on “Surf’s Up,” a Smile era tune that didn’t show up until the 1971 album by the same name, that crystallizes this vulnerable devotion. After a couple of verses of Van Dyke Parks babble, Brian rises above the song in one of those moments when all the walls between he and I—time, generations, product, my shitty speakers—dissolve, and the guy is hearing the message inside himself the moment he tells me. “I heard the word / Wonderful thing…,” he cries as he ascends into his glorious falsetto, and I know it’s the “gentle word” heard in “Good Vibrations:” love, and wisdom too, the wisdom that lies in the heart of hating to grow up—”A children’s song.”