Consider The Parking Lot

I recently joined up at my local gym one more time, though to my credit the last time I quit going it was because of the virus. The gym is attached to a UC medical center and mostly caters to med students, but locals can join as well. It is a decent place, nicer than many and not always crowded, but it can still be alienating, which is partly why it took me so long to rejoin. I don’t mind the repetition so much, but the psychological resources people draw on to motivate their routines can be unpleasant for folks with sensitive affect radars, and it’s sometimes tough to navigate the energies of pride, narcissism, envy, obsession, and grim determination that fluctuate both inside and out.

Like almost everyone there, I mitigate the vibes with an earbud brainlink, cushioning my spirit with Master of Puppets or Thee Sacred Souls or some esoteric podcast. When I fantasize about getting more hardcore at the gym, it’s less about adopting intense and demanding routines than about removing this cyborg buffer. I imagine mindfully submitting to my routine to the tune of dude grunts, piped-in lame-pop, clanking machines, and the airless hush of everyone else’s earbudded isolation from the room’s shared soundscape. But this sounds kinda like opting for dentistry without painkillers, which, sure, some Zen nuts I know do, but I am gonna need some serious satori before I show that kind of devotion to “whatever comes up.” Sometimes mindlessness is better.

Luckily, the men’s locker room has a dry sauna, the vibrant carrot at the the end of the whipping stick. I love saunas. I have enjoyed them in Finland and Istanbul and the East Village and the Oregon Country Fair. Med students are kinda dull, so the sauna here lacks social funk and character, and my aging buzzard body is often the only one that’s nude. But I am not complaining. Sauna leaves the bodymind springy and spacious, especially after a workout and a cold shower, while the hotbox itself offers another rich opportunity for meditative practice. The aim here is to maintain a cool head as the heat intensifies and the sweat comes, to rest without fidgeting in the face of itchy skin, the growing thirst and sense of alarm, and the urge to slump forward in that defeatist posture adopted by some sauna aficionandos. To “take the heat” this way you have to swallow it, transmute it, be with it, a tempering process that works on inner as well as outer planes, cooking and metabolizing this mysterious bodymind with the all-pervading radiance that yogis call tapas.

But such alchemy is not the gym mysterium I want to share with you here. This one lies back up on the main floor, where the stationary bikes, treadmills, and elliptical machines face a long bank of windows that curve vertically toward the sky above. The building itself lies at some elevation up the northern slopes of Mount Parnassus (now Mount Sutro), the tallest rise in the city, so the view is striking from the cardio machines, a magnificent if deeply bipolar scene split horizontally into two roughly equal visual zones.

The upper zone presents a sweeping San Francisco panorama that stretches from the heights of Lands End in the west to downtown in the east. Because of some perspectival happenstance, this picture is overwhelming green, as the overlapping treetops of Golden Gate Park, the Panhandle, and the Presidio queue up, on the far side of the Gate, the more distant undeveloped heights of the Marin headlands and beyond. While a few neighborhoods and prominent structures punctuate the topography — the orange pillars of the Golden Gate Bridge, USF’s charmless St. Ignatius, Temple Emanu-El’s Neo-Byzantine dome — someone unfamiliar with the city would assume the northern half of the thing was forest. This green layer cake is capped with the long arc of the Mount Tamalpais range, replete with the “sleeping Indian maiden” outlined by its eastern slopes — a settler-colonialist concoction that, like so many settler-colonialist concoctions, is tough to pry out of your brain once you have gotten the imprint.

There has been real weather around here of late, which means that the gym’s CinemaScope scene has been unusually active of late, decorated with storybook cumulus clouds (relatively rare in the Bay), and all manner of mists and silvery masses of water vapor. This stately scene is punctuated in turn with various birds, gulls and occasional geese, and the usual crows and other corvids duking it out in the shadowed air. I love birds and can watch them forever, and so you might think that my eyes, seeking a delight that might outpace the dull grind of the gym hamster wheels, would remain enveloped in the verdant and spacious upper regions before me. But no: time and again, regardless of cloud fantasia, or hawk play, or the wizardry that briefly paints the cypresses and gum trees in the slanting afternoon, my gaze falls toward the lower half of the scene before me, drawn like a moth to a flame or a meteorite to Earth by nothing more or less engaging than a parking lot.

It’s a particularly aggravating parking lot, the uppermost level of the institution’s large and now rather antiquated garage. The lot was designed with compact cars in mind, which sorta don’t exist anymore, at least as a category that most drivers think about, and its narrow lanes leave scant room to comfortably maneuver. It is usually pretty full, and a lot of the people angling for spots are already having a tough time, with friends or family sick or dying in the hospital, or themselves on the hook for some mystery plaint. As such, the parking lot, an already claustrophobic domain of luck, frustration, and occasional rage, becomes a literally concrete metaphor for the mortal condition that brought most folks here, the same lot in life that also brought me, through a somewhat less pressing route, to the exercise machines looming over the scene.

Sickness and parking lots both reveal a similar twist of the mortal coil. Call it weightiness. There you are, cruising through life in your sometimes fleet and mercurial vehicle, when the demands of the hour expose those vectors of speed and spirit to be heavy, sluggish, fragile, and awkward things requiring constrained operations and sometimes major repair. While I don’t believe this simple dualism accurately reflects the actual relations of mind and body, our experience of cars sure thickens that paradigm. We are all gnostics when we can’t find a place to park.

Sometimes when I am frustrated in traffic I feel a bond, half-fantasized but so what, with all the millions of people similarly locked into misery across the planet at that precise moment. Similarly, the UC parking lot’s contest of logistical annoyance and mortal suffering, of fear and quiet resolve, unites what is otherwise an unusually diverse population, at least for San Francisco: all manner of colors, ages, and classes spill out of those vehicles, from cocky gang-bangers and stressed soccer moms to hawk-nosed businessmen and clueless little kids clutching anxious bouquets. The whole human tragi-comedy is on display in this oily labyrinth, which stages a stuttered series of micro dramas almost designed to hook the mind into the hilarious hassle of finitude. You can try to keep your head up high, and surf that plotless blue, that distant green, those avian palaces of cloud. But it’s hard to not fall for one more tale of the parking lot.

Also…

(•) Magic & Science

I met Jeffrey Mishlove last fall at a DMT event in England. Mishlove is an OG alternative thought leader, famous for his deeply ’70s anthology The Roots of Consciousness and especially for his minimalist interview show Thinking Allowed, which ran from the late ’80s until the early 2000s and included every visionary brainiac, New Age weirdo, and paranormal superstar under the sun. Now well into his seventies himself, Mishlove is back with New Thinking Allowed. He also kindly invited me on the show to talk Techgnosis, which is a quarter century old this year. It’s a bit weird to go over such ancient territory, but to judge from the interviews I have been giving lately, the book is experiencing yet another bout of relevance, spurred by esoteric TikTok and “godposting” and the chatbot apocalypse. The resulting conversation with Jeffrey turned out to be fresh.

(•) “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down”

I wrote a short appreciation of one of my favorite songs for HiLobrow’s Dolly Your Enthusiasm series of critical riffs on classic country tracks. It’s a fine series, and my appreciation for HiLobrow editor Josh Glenn’s longstanding labors of love and obsession continues. I love Johnny Cash’s version of “Sunday Mornin’”, of course, but I prefer Kris Kristofferson’s own take, which has the most pathos and grit. I write that Kristofferson’s song “leaps, or rather drifts, into that temporal breach between sacred and profane, and becomes thereby perhaps the most reverent of godless American ballads.” The rest.

Watching

I was blessed to attend university at a time when film societies, often student-run, packed the weekends with cinema, an experience that left me with a deep love and appreciation for the postwar canon of international art film. That makes me a pretty happy subscriber to the Criterion Channel, which features a fine Janus-faced archive of classics, many of which I haven’t seen in twenty or thirty years now. The service also offers some fun (if sometimes frustrating) ways to interact with its trove in comparison to the usual streaming services. Instead of search fields and AI recommends, you gotta dig down through a slowly-shifting bank of curated categories, a process that can help you identify that evening’s vibe (Snow Westerns anyone?) as well as discover new films clustered alongside loved classics.

Trawling through a Criterion collection of Cinema Verité docs, I stumbled across a Les Blank film that I had heard about but never seen: A Poem is a Naked Person, a 1974 documentary loosely centered on singer and keyboardist Leon Russell, who cut his teeth as a session musician in 60s LA but was in full gospel boogie mode by the time Blank caught up with the star in his native Oklahoma, where he was building a new studio. Not unlike Robert Frank’s Cocksucker Blues, rights issues made A Poem is a Naked Person tough to see for decades. But while Frank’s tawdry and revealing scatter-shot verité remains officially unreleased, Blank’s funnier but still gnarly gumbo got the proper Criterion treatment in 2015, a couple years after the filmmaker’s death.

As in so many of his films, Blank, a long-time resident of Berkeley, indulges in his love and fascination of regional cultures that resist the mass entertainment age. But Poem is more experimental than most, an ambitious montage film marked by the influence of Godard films like Weekend and Pierrot le Fou. The whole thing’s a crazy quilt or “floating mental institute” of images and orthogonal events; soundtracks bleed over into one another, while random spoken phrases are sometimes transformed into onscreen titles that ring with metaphysical overtones. “Either way you go it’s the same thing” says one concert guard.

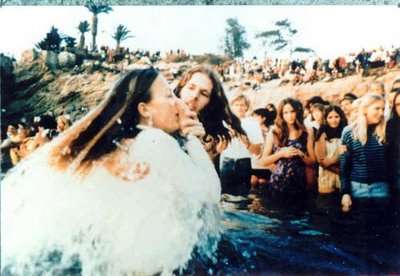

Russell seems an impish, fun-loving, and somewhat cynical entertainer, giving the kids who missed the sixties the hot grooves they want. Blank includes some smoking concert footage and studio performances — including a somewhat bemused George Jones doing “Take Me.” You also get the obligatory rock star footage of semi-nude partying and flirtations with young female fans that seem, at this point, almost innocent in their polite lewdness. One funny scene features the handsome but less cool Eric Andersen visiting with Leon and, in addition to mistaking him for a much older man because of the silver hair, wonders where the revivalist fire of Russell’s performances come from. “That’s my illusion,” says Leon. “Don’t get too throwed off by that.”

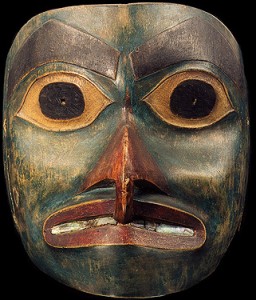

Russell is no genius, no Rolling Stones, and Poem achieves its lasting interest by embedding the music stuff in a psychedelic mosaic of weird Americana. We see a folk art totem pole, a pie-eating contest, a parachutist trying and failing and finally succeeding to eat glass. We visit a banjo pick manufacturer, a Tulsa Pow-Wow, and the inevitable Black church “All power!” hoedown. But the fun and sideshow novelties are also stitched up with insecurity, fear, and the era’s harrowing threat of wayweird drift. We see little kids screaming, a hippie arrested, a boa constrictor crushing a baby chick, a building demolished before spectators. One young man in the studio, his voice run through an ominous echo, asks the questions of a dissipating age: “Who am I to believe? Who am I gonna entrust my feelings to? You get disillusioned, and it gets all faded out.”

One unexpected pleasure for this student of the era was the onscreen presence of Jim Franklin; the legendary illustrator and cartoonist who helped put Austin on the hippie map was apparently part of Russell’s entourage. We see Franklin in Russell’s empty pool, capturing scorpions in an open jar, and then painting the surfaces with a glorious celebration of cosmic and animal life. Franklin is also quite the freak ranter. He rants about animals, about other people’s self-concepts, about art. “A lot of people are walking around with an incredible amount of painting ability but they just never do it because they got scared by it once or someone told them they weren’t doing it right. Which is absurd! How are you gonna say which painting is done right? Ask Picasso, which painting did you do right? They all look fucked up. That’s the way he wanted them to look. Fucked up like the mind is.”

In 1979, Robert Christgau dug into Blank in a long article, declaring A Poem is a Naked Person an “arty horror movie of a documentary.” Maybe it looked this way by the late 70s, when this rag-tag absurdist shit had soured. But for fans and students of that decade’s earlier Zone and its oracular and sometimes gaudy fascinations, Poem is a treat that gets under your skin. It’s fucked up like the mind of America is.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar.