Please lose yourself in this book

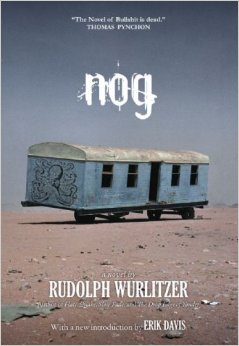

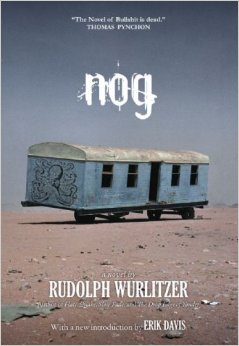

To wind up a cult classic is not, perhaps, the most enviable fate for a book. But it is not the worst of worlds either, because cult means more than simple obscurity. The word also suggests mystery, like the mystery cults of antiquity, with their underground revelations and fanatic sharing of secrets. Nog, Rudolph Wurlitzer’s debut novel, is a cult classic in this deeper, more initiatory sense. The novel shines from the margins, as brilliant as it is obscure, as demotic as it is experimental. After attracting passionate fans over forty years of slipping in and out of print, Nog now reappears on the shelves, like a mushroom that’s been waiting for the right mix of moisture and shade to fruit. Will you swallow it whole?

For make no mistake: this peculiar, funny, and disturbing book is more than an exercise in the literature of exhaustion. Reading Nog can also be an initiation of sorts, or at least a strange and pitilessly illuminating trip. This is as it should be, for it was published in the hot and heady year of 1968, when America’s exploding counterculture was pushing the envelope of experience to the breaking point of intensity and anomie. So while Nog’s impersonal dialogue and nihilistic undertow reflects the “postmodern” literary concerns of the time, the novel is also a paradoxical manifestation of the ethos of experience that impelled so many Beats and freaks and longhairs on an errant journey of consciousness that could be as aimless and desperate as it was joyous or spiritual. Wurlitzer’s protagonist is on a journey as well, although it is more than a little aimless. A wanderer who floats about the West Coast, Nog discards and invents memories and motivations while drifting through a variety of hippie scenes. At the same time, another journey is unfolding, as Wurlitzer’s language wanders to the very edges of subjectivity, where the narrator’s stream of consciousness spills and swirls outside of the ordinary boundaries of selfhood.

This experiment inevitably worms its way into the reader’s head as well. For there is no way to follow the errant path of this strange nonhero—who may or may not actually be named Nog—without being infected with Wurlitzer’s half-catatonic, half-Zen deconstruction of our ordinary experience of self and language. Though Nog is in no ways philosophical, the fractured, disassociated voice of its narrator reflects a sobering philosophical recognition that our fundamental sense of identity—of being an agent who possesses personality, desire, memory—is in many ways a fabrication, if not an outright illusion. This realization is the esoteric kernel of the 60s consciousness, the empty diamond at the heart of LSD. Its recognition could take one towards Asian mysticism, with its dismissal of ordinary personality, as readily as it might heighten the desire to drown this no-self in hedonism. But there is a literary expression of the predicament as well, for one of the foundations of the constructed self—perhaps the primary material—is language. I, me, mine are all words that anchor the turbulent stream of consciousness, giving “us” a toe-hold amid a ceaseless flow of sensations and impulses. By turning language back on itself, by experimenting with its forms and forces, the apparent solidity of the “I” we try to hang our hats on begins to dissolve. “The subject,” as the French philosophes would have it, disappears.

If the self is a story we tell ourselves, then those avant-garde story-tellers eager and willing to undermine their own game become hermenauts of the new subjectivity. In Ulysses, Joyce experimented with the forms of fiction in order to experiment with subjectivity itself, and especially to probe the contours and paradoxes of the “stream of consciousness” that William James had established as the foundation of human perception. Joyce made room for epiphany, but in the works of a number of challenging postwar novelists—including Burroughs, Beckett, and Robbe-Grillet—the tango between self and language grows increasingly desultory, aphasiac, and absurd. Perhaps the most comic example is Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, whose protagonist Tyrone Slothrop simply disappears in the second half of the novel, with neither rhyme nor reason.

Wurlitzer shares the experimental bravura and wry irony of many postmodern writers, but the loss of self he depicts is less a condition than a kind of quest. Nog, in other words, is a fugitive from subjectivity. His drift is a flight. In the words of the West Coast Beat poet Lew Welch, he wants to “kick […] the habit, finally, of Self, of / man-hooked Man.” In good 60s fashion, Nog shifts his dissolving consciousness with various practices of body and mind: he (possibly) steals his name from another man, he stares at the ocean or at cracks in the floor, he fabricates memories and keeps them to a minimum. He interrupts desire and decision whenever possible, and submits with nihilistic abandon when the imp of the perverse rears his head.

Of course, Nog’s rather successful quest to erase his personal history—in don Juan’s memorable phrase—is rooted in Wurlitzer’s own personal history, which wended its way through the labyrinths of the era’s bohemias. As an heir to the dwindled Wurlitzer music machine fortune, Wurlitzer grew up enmeshed in a skein of conformity and modest privilege. In the early 1960s, he set to wandering, dropping out of Columbia for a heady spell in Castro’s exuberant young Cuba before spending two years testing cold-weather equipment in the army. In the remainder of the decade, Wurlitzer drifted through the demimondes of Paris and Majorca, Manhattan and California, whose teepee communes and hippie crash pads lend the ballast of cultural specificity to Nog’s acid-saturated dissolve. Strongly inspired by the literary experiments of the Beats and the French avant-garde, Wurlitzer also drew his language from music, especially the nonlinearity of free jazz and the unvarnished laments of the “rediscovered” bluesmen. In conversation, Wurlitzer noted that figures like Mississippi John Hurt “gave me the courage to slide into my own miasma, and expose what ‘is’, beyond good and bad, never mind evil.” That courage also enabled Wurlitzer to expose the metaphysical drift that lurked beneath the explosive dynamism of the scene. This alone makes Nog one of the greatest novels of the counterculture.

Like many of his peers, Wurlitzer would later attempt to understand his own alienation through an engagement with Buddhism, whose core insight into the unreality of self affirms the nothingness at the heart of Nog while paving the way for a compassionate exit from nihilism. This generational drift to the east, already implied in the novel, is matched by a complementary desire to “Go west” as well—not just the west represented by California, where everything ends, but the west of the western, whose mythology shaped the imagination of Wurlitzer’s generation. One chapter actually begins with a frontier scene that the narrator immediately interrupts and rejects as “too far back.” Later Nog later steals a Stetson from a dying cowboy, before taking on a feral colony of freaks holed up, Charles Manson-like, in a ghost town. Decades later, Wurlitzer would write a comic western novel, The Drop Edge of Yonder, and his screenplay for Sam Peckinpah’s fabulous 1973 film Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid cemented the link between the counterculture and the scruffy, antinomian drift of the wild west.

But even as Nog gives off the fragrance of a gone world of ghost towns and urban communes, the novel is no time capsule. Wurlitzer is far more concerned with dissolving historical identity that with shoring it up. While the novel’s setting lends it the density of time and place, that only allows gives the dissolution its language effects more to feed on. Nog moves with a kind of desolate immediacy that eludes narrative and sidesteps identity, dodging aphasia and enlightenment alike. His loss is, perhaps, ours as well. But before the void there is the journey, the long strange trip from no-where to no-one.