Blessed By the Night: The Dark Metal Compilation and Opeth’s Blackwater Park

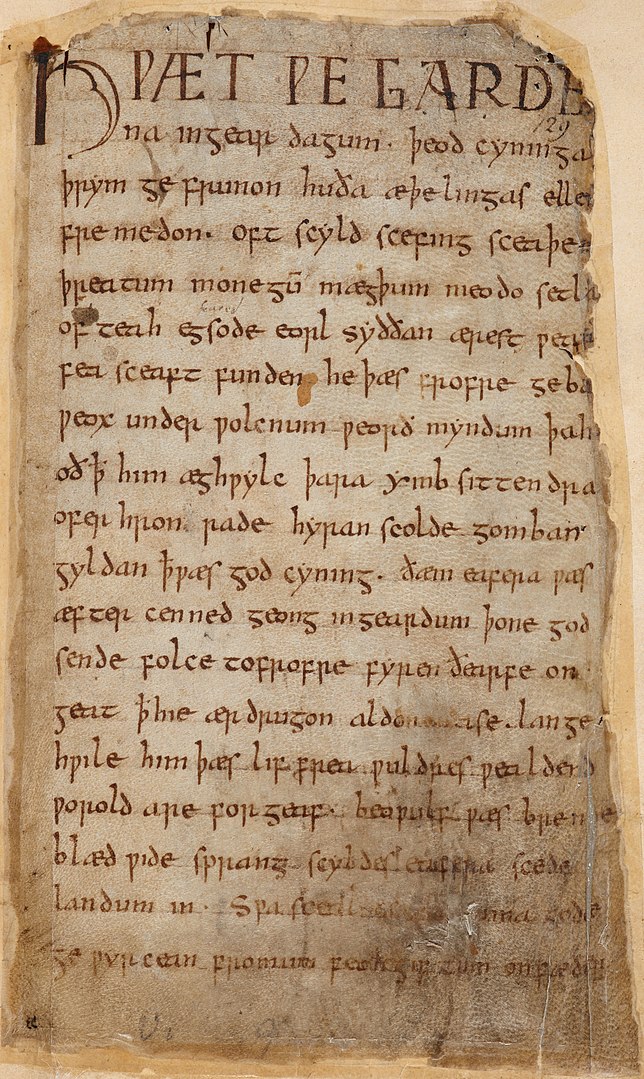

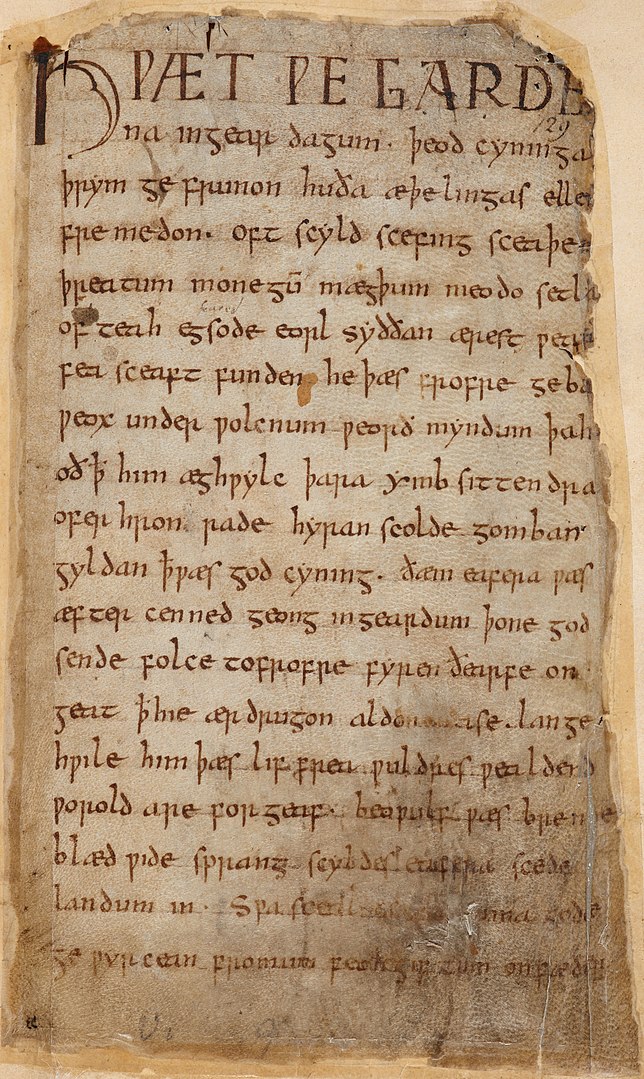

When he wasn’t writing about hobbits, J.R.R. Tolkien studied Northern European languages at Oxford, and the most important thing he did as a scholar was to transform our experience of the old Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf. Before Tolkien, academics treated the work as a linguistic ruin, historically useful but too full of stupid monsters to count as literature. In contrast, Tolkien not only argued that Beowulf was a fully realized work of imagination, but that the poem’s power derived precisely from the presence of the monsters. Tolkien pointed out that, unlike the baddies in Homer, where even an asshole cyclops like Polyphemus could still be the son of a glorious god like Poseidon, the monsters of the Northern imagination were irredeemably horrible — a chaotic, almost Lovecraftian crew that would, at the end of time, gobble up men, the gods, and the cosmos itself. The fact that the monsters were destined to win the ultimate battle explains the peculiar melancholic power of the Northern heroes, who fought with courage but without hope.

Something of this imagination is still alive and kicking, at least in black metal, a thoroughly globalized music that comes mainly from the land of the ice and snow. The glory days of Scandinavian black metal began over a decade ago, when Oslo gloomsters like Mayhem, Emperor, Dark Throne, and Burzum hoisted the Satanic banners nicked from ’80s bands like Venom and Bathory over the ever-mutating engines of extreme riffage. While embracing the postmodern nihilism of death metal, with its speed, atonal aggression, and growled, unintelligible lyrics, Norwegian black metallers also tuned into the more spectral energies of, well, evil. Cookie Monster was still on the mic, but now he was wearing corpse paint.

In terms of Tolkien’s reading of Beowulf, you could say that black metallers identified with the monsters of chaos the most obvious and available one being Satan. But as the scene mushroomed across the North, many bands shifted their allegiance from the enemy of God to His pagan predecessors, especially Odin and Thor. In other words, these guys didn’t just identify with the monsters — they also wore the grim mask of the Northern warrior. By combining bummer vibes with righteous gloom, black metals evil pose could become as extreme as its sound, leading to a dark aesthetic so fantastically over the top that it neutralizes all attempts at satire from the get-go. Its easy to make fun of the Scorpions, but where do you start, for example, with a Finnish band that calls itself Impaled Nazarene?

Writing in the esoteric journal Aorta, the Austrian occultist Kadmon calls black metal “a werewolf romanticism.” Obviously, this sort of mythic indulgence can go south fast: Black metal has played a role in the recent resurgence of Germanic pagan fascism, and racism continues to dog the fringes of the subculture. But the more lasting outcome of this romanticism is inclusive, at least musically speaking. Because once black metal opened the door to romanticism, it could not prevent the Gothic from waltzing in, spoiling the Viking gruff with absinthe and lace. Though genre-splicing is an endless game with metal, a lot of music now marketed as black metal embraces gloomy melodies, epic keyboards, female vocals, Hammer-film ambiance, neo-medieval acoustic guitars, even flutes. Though often “progressive” in feel, these steps are really moves toward accessibility, or at least listenability — in other words, pop.

Thats why the German label Angelstar was wise to subtitle their recent two-CD Blessed by the Night compilation as “dark metal” rather than black. Like the Nuclear Blast compilation series Beauty in Darkness, the Angelstar discs highlight the more hummable wing of the music. The first cut, by the Americans Aesma Daaeva, shows how far we have come from the Beelzebub bop of the early Oslo scene: a superbly-trained female voice chants “Oh Death” over a classical guitar, whose arpeggios are soon overtaken by mild blastbeats and keyboards lifted from the first Halloween movie. Songs like Tristania’s “Beyond the Veil” and Vintersorg’s “Svälivinter” feature wailing Valkyries, Renaissance pluckings, and thoroughly gendered duets of beauty and the beast. Both metal and Goth have long had classical fixations, and their fused drive towards the operatic reaches its apex in the contribution by Therion, a glorious slice of pomp which not only sounds like it’s from “Carmina Burana” but actually is from “Carmina Burana.”

Blessed by the Night still features plenty of gut-shrieks, Satan chants and mispronunciations of “Samhain.” Satyricon serves up an admirable death metal bass-drum blur, memorably characterized by the Heavy Metal FAQ as “an undulating wall of sound that conditions listeners to act out the diabolical bidding of the bands and their master, Satan.” In their cut “Fallen Skin Dimensions,” the Austrian act Third Moon present a perfect blend of conventional tunesmithery and nihilistic mess, pushing their syncopated beats and witchy melodies to the edge of incoherence. And Dimmu Borgir, a band popular enough to have garnered a nomination for the Norwegian equivalent of a Grammy, bring an appealing trollish swing to their relatively blistering “Moonchild Domain.” Chords slide by like broken slabs of ice, while evil elven keyboards play eighth note melodies that skitter around like dolls in a mad Santa’s shop.

In some ways, the mainstreaming of black metal resembles the transformation of the Klingons on Star Trek: originally barbaric and one dimensional bad guys, they grow sympathetic as we learn of their myths, their rituals, their women. From a commercial point of view, this makes perfect sense, though it’s precisely this kind of accommodation to conventional human taste that extreme metal has long attempted to purge through its sonic nihilism. “True” black metalheads bemoan even the snarling likes of Dimmu Borgir, and most of Blessed by the Night would make them gag.

And you can’t really fault them. It’s tough to go velvet while still getting medieval on your ass, and much of the music on Blessed by the Night resembles Enigma on steroids. The return of glossy rock drums is an abject failure, the keyboards often sound like they were lifted from old video games, and the cut-rate Dead Can Dance moves lack that band’s flare for exotica. On the other hand, if you allow yourself a little of that old suspension of disbelief, this eclectic and emotionally dramatic music has plenty of room for marvels. In “View from Nihil,” the latest Mayhem singer sounds like Mark E. Smith channeling Beckett on a drill sergeants megaphone, while the Swedish band Otyg digs so deep into their folk roots they sound like Danzig playing a hoe-down for dwarves. Still, most of these bands simply do not have the chops or the taste to back up their lofty aspirations. They fall flat, like Lucifer stubbing his toe on the gates of hell.

One blackish metal band that has amassed enough hit points to risk such adventures is the Swedish group Opeth, who has built up a small but fanatical cult since their wrenching 1994 debut Orchid. Avoiding the cornier trappings of goth-metal and the Satanic hordes, Opeth still paint on an epic canvas, sounding at times like black metal’s answer to 70s King Crimson. Restless with moods and melodic lines, their impressively long songs flow and unfold over shifting blocks of rhythmic ice. But even their more wankier passages remain rooted to the riff, which gets Opeth’s mastermind, Mikael Åkerfeldt, a golden star in my prog rock book. He has also perfected the dynamic tension that has driven many of the most expressive metal bands since Led Zeppelin: the interplay of quiet and crude, of shivering acoustic passages and brutal electric squalls. In fact, Opeth’s “blackness” lies less in the music then in Åkerfeldts morbid lyric obsessions (death, despair, misery) and tonsil-shredding vocals, which he nonetheless varies with what has become, over the course of five albums, an increasingly convincing “clean” voice. Lately, hes even been willing to slip in ballads about eek! girls.

The new Blackwater Park continues to open up Opeth’s sound. Producer Steve Wilson, who fronts a pop-prog act called Porcupine Tree that manages to be both off-kilter and straight-ahead at the same time, fills out Opeth’s sound with shiny riffs, nifty vocal filters, and the occasional electronic blurp. Despite delightful eruptions of atonality and old school prog moves, many songs here are repetitious and conventionally structured, and so wear their length more tediously than on 1999s amazing Still Life. Still, you would be amiss to call Blackwater Park “pop,” even in the sense that Blessed by the Night is pop. While the eleven-minute “The Drapery Falls” starts out with catchy choruses and lots of acoustic strumming, the tune gets twisted after the five minute mark, with ice-cave vocals, crazy Frippertronics, and manic beats from the two Uruguayans named Martin who back up Åkerfeldt and guitarist Peter Lindfren on bass and drums.

Despite lyrics about coffins, crypts, and drapery, Opeth’s Romantic spirit manifests itself less in Gothic trappings than in the strange vulnerability with which Åkerfeldt presents bleak and blasted emotions. Åkerfeldt’s melancholy is now more believable than his rage, and the album’s strongest passages are almost entirely the mellow ones. After twisting and turning through a fistful of angry riffs, “The Leper Affinity” ends with Åkerfeldt on the grand piano, tinkling out rainy day ruminations that simply drift away to a diminished end. Even the “evil” vocals don’t communicate Viking fury so much as the desperation and weakness with which we submit finally to anger and despair, like a trapped animal or the “derelict child” mentioned in “The Funeral Portrait.” In essence, Åkerfeldt does for the black metal bad guy what John Gardner did for Beowulf’s foe in his book Grendel: he gets inside the monster to reveal its sad confusion, its helpless knowledge that it will, in the end, be swallowed up by the very darkness that fills its sinews with might.