The other day a friend sent me “The Elite Capture of Substack,” a post by Cydney Hayes that got a lot of play over the last year. The piece tracked the enshittification of the platform, principally through the introduction of Notes and the feedy shift in focus towards “stacking” and “restacking” and other social media circus acts. Hayes, deploying her generation’s uncanny appropriation of old hippie slang, described it as “a vibe shift”: “From quality to quantity; from recognized intellect to symbolic trophies; from growth in our collective writing skills to growth in subscribers, and in turn, growth in users and profit for Substack.” It’s the sound of the hamster wheel spinning: click, click, click.

I don’t use Notes myself, unlike Hayes, who from all appearances posts there all the fucking time. My experience of the enshittification of the platform has more to do with the pressures put on users of the platform, readers as well as producers, to keep the flow coming fast and furious. As a reader, I tend to “manage” my Substack feeds in erratic bursts of feast or famine. Flush with a new-born fascination with Internet talk, and optimistic about an expanding universe of essay writing, I might subscribe to dozens of newsletters all at once, sometimes throwing my cash into the ring to show my commitment, to myself as much as anyone. Within a few weeks, the winnowing already begins, until soon enough I am left with only a couple regular newsletters in my inbox, which I still largely use rather that the Substack app. This condition persists until, moonlike, I wax expansive again, an enthusiasm for hot new discourse mingled with the anxiety that without some new feeds I will sink into a silo of my own making.

The reality is that there just aren’t that many voices or points of view I want to hear from that regularly. I don’t read online that much, or at least I try not to, especially when I want to get some serious work or play done, not to mention continue my devotion to reading deep and sometimes difficult, you know, books. Substack subscriptions pile up like stacks of New Yorkers, except in cyberspace. I would be happier if more people published essays at the rate I do here on Burning Shore, but I promise you that is not a successful strategy, at least by those measures of success that do not highly weight chillage.

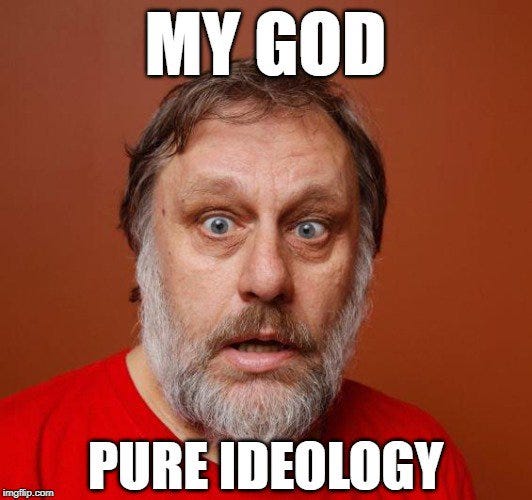

I am on the famine side of the wave at the moment, but one feed that has escaped the knife so far is the philosopher Slavoj Žižek’s Goads and Prods (I also want to give shout-outs to Rave New World, Sleeveen, and The Convivial Society). It’s partly a nostalgia thing. If you know the Ziz, you won’t be surprised to learn that Goads and Prods provides political commentary, cultural criticism, and Lacanian rants from an increasingly conservative atheist materialist who can be funny, paradoxical, irritating, and occasionally repulsive, particularly when it comes to his not so sublimated fantasies of revolutionary violence.

The Ziz has always been prolific, which means that he is well suited to the rhythms of the Net, cranking out two posts a week. But again, as longtime readers know, Žižek’s churn has always been wedded to an almost hysterical level of repetition and what could only be called self-plagiarism, or perhaps auto-collage. It’s as if Žižek long ago learned to be his own LLM, which some of the writing on the Substack very much suggests. A recent post, “The Minotaur’s Death Cramps,” included the following passage:

With state monopoly gradually disappearing limits ruthless exploitation domination imposed by state also disappear original idea cryptocurrencies new space freedom without external authority control ends up what Malabou herself calls “combination—senseless monstrous unprecedented—savage verticality uncontrollable horizontality.”

Call me old-fashioned, but I believe it’s a simple courtesy to copyedit your posts, even if you have to pay someone to do it (which I do). It’s like wiping the snot off your face before entering a restaurant. But this weird chunk of text doesn’t even read like a rough draft, but something more inhuman, as if it were generated by a wonky algorithm. Or maybe the passage is the symptomatic eruption of the babbling language machine that Žižek’s psychoanalytic hero Jacques Lacan identified with the unconscious, poking up its iterative nonsense head in the midst of the performance of authoritative knowingness that is the stock in trade of most public intellectuals.

I have been reading the Ziz since the 90s, when I once interviewed him in a hotel room as he hopped around looking for his Xanax. I like the avuncular crankiness of his literary voice, the vulnerable humor of his slobbery persona, and his loop-de-loop deployment of philosophy, theory, history, even pop physics. Intellectually, this stuff is mother’s milk to me, though I easily tire of academic writing these days, and no longer consider myself a materialist (I used to think of myself as a psychedelic materialist, à la Deleuze; now I am more of a whatthefuckist). Most of all, I admire and enjoy Žižek’s perverse skills as a cultural critic. He is capable of reading all manner of unexpected material—dumb movies, classical music, Internet memes—as intricate and illuminating symptoms of an infernal set of contradictions that is both inside us and without us. I find him particularly provocative on religion—at least Abrahamic religions. His 2024 post “A Glance into the Archives of Islam”, a long Lacanian riff on the tension between Abraham and Hagar, was fantastically rich. Goads and Prods also reflects his invigorating and long-standing materialist take on Christianity, a vision in which God dies on the cross—as in kaput, no more God—and the community is left to make its way into the atheist future with a post-religious gift of potentially radical and militant ethical commitment.

Unfortunately, Žižek pretty much sucks rocks when it comes to Asian religions and their various post-hippie Western adaptations. Not only does he hate Buddhism, the Bhagavad Gita, and contemporary meditation culture, but he shows his militant disdain by not offering a shred of the hermeneutic sympathy he lends the often horrific religion(s) of Christianity. A lot of the time, he doesn’t even bother to get the facts right (there is a small online industry in pointing out his errors). Decades on, the strident critique still churns. “The Buddhist Ethic and the Spirit of Global Capitalism,” a popular post from last June, based on a lecture given in 2012 that auto-samples a Cabinet piece he first published almost a quarter century ago. Though there’s some new stuff about a lazy documentary, the ideological gotcha is the same.

…although “Western Buddhism” presents itself as the remedy against the stressful tension of capitalist dynamics, allowing us to uncouple and retain inner peace and Gelassenheit, it actually functions as its perfect ideological supplement….Instead of trying to cope with the accelerating rhythm of technological progress and social change, one should renounce the effort to control events, rejecting it as an expression of modern domination. Instead, one should “let oneself go,” drifting along while maintaining an inner distance and indifference to the frenetic pace of change, based on the insight that all this social and technological upheaval is ultimately a non-substantial proliferation of semblances that do not concern the core of our being.

Žižek concludes that, “The ‘Western Buddhist’ meditative stance is arguably the most efficient way for us to fully participate in capitalist dynamics while retaining the appearance of mental sanity.” The idea here is that meditation, as it is presented by “Western Buddhism,” enables you to plunge into the capitalist game while sustaining the perception that you are not really in it, and that what really matters to you is the “peace of the inner Self to which you know you can always withdraw.”

I am not gonna play an authenticity game by declaring the trends Žižek identifies to be false, heretical, or even jejune. Religions and spiritual practice traditions are contradictory and ambiguous things, and they produce all manner of monsters—and infinite opportunities for hermeneutics, sympathetic or critical. All the trends that Žižek identifies are found in the contemporary dharma, commingled as it often is with the wellness industry, or what I like to call surveillance wellness. But I do need to insist that this is not at all the dharma I have learned or encountered among the teachers, sanghas, and texts that have fed me most along the path. I’ll take some peace when I can get it, sure, but nothing has ever led me to get comfortably numb with an inner Self, that old navel-gazing stereotype that Timothy Morton, in his attack on the “Buddhaphobia” of Žižek and others, traces back to Hegel’s know-nothing—or maybe no Nothing—dismissal of the dharma as nihilistic.

That said, there are good reasons to take the Ziz’s critique seriously, because he legitimately identifies many lazy and all too predictable dharma mutations out there in our world of turbo-driven self-optimizing therapeutics. A decade ago, a post on the Speculative Non-Buddhism blog—which harshly attacked Western or “x-buddhisms”—shared a YouTube video shot at Wisdom 2.0, a San Francisco conference that targets the commingling of Asian wisdom traditions with corporate culture. Those were the days of the “Google bus” protests, and during one mindfulness workshop, antipoverty activists interrupted the proceedings to accuse Google of decimating local San Francisco neighborhoods through aggressive tactics of gentrification. The mindfulness trainer responds to the protesters by, as the Speculative Non-Buddhists put it anyway, advising the attendees on how to dissociate themselves from the protest. “This is sort of an important moment,” he says. “We can sort of leave this moment as something we didn’t expect to have happen, and it happened, and it’s wrong. Or we can actually use this as a moment of practice. Check in with your body, and see what’s happening, what it’s like to be around conflict with people with heartfelt ideas that may be different than what we’re thinking. So, let’s just take a second and see what it’s like.”

That’s not the worst advice in any conflict, and protestors have their own tactics of dissociation and false consciousness. But you get the drift. How much do meditation practices, which produce real if open-ended shifts in awareness and perception, wind up principally managing the sort of stresses that, left alone, might erupt in more structural and collective change? Consider the “ZenBooth” or “Mindful Practice Room” that Amazon introduced to its warehouses a couple years ago (I believe they are no longer to be found). Part of the “AmaZen” program, the small booth offered employees some on-screen mindfulness programs to help them manage their “mental and emotional well-being” and “recharge their internal battery.” Given the notorious brutality of Amazon’s warehouse conditions, “parody” doesn’t quite encompass the bleak absurdity of this object, which literally incarnates the precious and boxed-in interiority that Žižek critiques.

Of course, plenty of Buddhists and modern meditators hate this shit and work against it. Buddhists have been criticizing “McMindfulness” for years, some pointing out that, shorn of the dharma’s soteriological (and religious) claims, a deracinated mindfulness practice all too easily melts into mental massage oil, gently greasing the engine that is driving us off the cliff. But we are always in some version of this predicament: fashioning keys inside locked rooms, using the master’s tools. Practices of mind and mindfulness do not necessarily liberate in themselves, and they may lead to newer and subtler trances. But to glimpse other possibilities, personal as well as social, the eye must be retrained, or released from its usual grip on things. For many of us, pragmatically engaging the mind that hosts and clings to thought creates more space—and is still complemented by the suspicions of critical discourse.

Swiping a move from Žižek, I want to dust off an episode of the 70s TV series Kung Fu, a show that managed to be simultaneously dumb, excellent, and profoundly influential. In the twelfth episode of the show, in which David Carradine’s Kwai Chang Caine wanders the Old West in search of his brother, Caine is falsely convicted of a crime and roped into a labor camp, forced to dig out a mine. It’s the brutal nadir of capitalist relations: inhuman and illegal slavery for the sovereign sake of greed. The main instrument of control is tossing men into “the Oven”: an iron box that intensifies heat and cold. Men confined to the Oven are dragged out barely alive, or possibly dead. After some of the inevitable righteous slo-mo ass-kicking, Caine is put into the Oven along with another convict, who soon starts to suffer terribly. Best to just watch the short scene:

By teaching the man to meditate, both Caine and his comrade resist the brutal order of the day. Here we see the adoption of an internal meditative practice of homeostatic regulation and its concomitant gift of mental strength, or total passivity, take your pick. The practice comes wrapped in some poetic metaphors, and requires some new beliefs, which are either charming or hokey or both, and it doesn’t really matter because the proof is in the pudding. (I have felt my body become my breath, become as light as a feather, and it feels spacious, expansive, and unrelated to my hatred, or not, of surveillance capitalism.) Caine is basically teaching a mindfulness stress reduction regimen. But here this “Western Buddhist” (get it?) practice is not individualist but social: something passed from person to person (“Sit like me”), requiring trust and an opening to otherness, and resulting in a modification of the collective body that is politically engaged, or at least resistant. Later, when the mine collapses and the men are trapped underground, Caine urges them not to waste their breath on freaking out, and to down-regulate their bodies into sleep as a way to conserve the air while the rescuers dig them out. Passivity, or passive activism?

So how should we compare the Oven to the ZenBooth? Is the prison in our mind or are we in the prison? If mindfulness, or other psycho-spiritual therapeutics, are always “ideology,” the ideology seems to shift depending on who is packaging the practices. Emerging from below, or from the margins, as modes of survival or everyday becoming, spiritual techniques can serve the cause of dignity, sympathy, and resistance. But they can also be manipulated into forms of deferral and dissociation, especially when they become absorbed into the self-optimization routines of the entrepreneurial self. But what does this say about the practices themselves? That they are the ultimate forms of fetishistic disavowal? Or that they are multivalent, dependent on context, and without an essence, political or otherwise. Just as the dharma would have it.

There is an important theoretical issue here as well. In his critique of anti-Buddhist theorists like Žižek, Marcus Boon writes that they “need to examine their own fear of bare life, and their avoidance of consensual practices that examine and realize states of non-knowledge.” This requires some brief unpacking. “Bare life” is the reduction of the human to biological life, separated from the projects, meanings and practices that make us human. It is what torturers and jailers and uncorked sovereigns do.

But meditation offers another possibility of bare life: just this body, just this breath, loosened from thought, personality, projection, and identity. Suspended in history, a living punctum. But this vision of bare life is a terrifying thing for many intellectuals, because it requires getting close to zero, which means releasing their primary means of fetishistic disavowal: discourse itself. The world ahead of us is a world of myriad altered states, mutations in consciousness, virtual dematerializations, and psychoactive slipstreams. Best to explore the possibility of experiencing ourselves, and recognizing aspects of the mind, that are not entirely locked into the carceral influencing networks of knowledge, information, and discourse. In other words, states of “non-knowledge,” light as a feather.

Upcoming Events

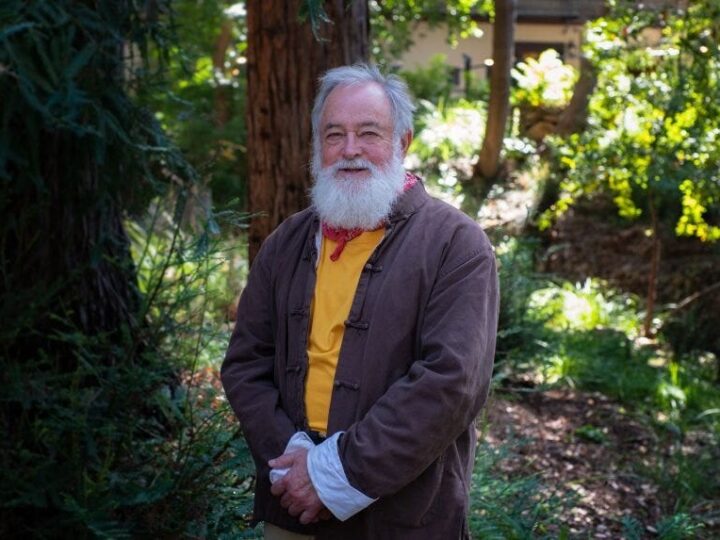

• “Practicing with Practice.” On Sunday, January 5, at the Berkeley Alembic, from 2 to 5 pm, I will host a conversational workshop with my brilliant and charming partner, Jennifer Dumpert. “Practicing with Practice” will create a space for folks to play with and talk about spiritual, religious, and aesthetic “practice,” which is also the subject of Jennifer’s current book project. This term lies at the heart of many people’s lived experience, and for good reason. According Michel Foucault and Peter Sloterdijk, humans are at root “practicing beings” who to some degree make ourselves through what we do. But what do we mean by the term? How does “practicing” meditation or yoga relate to other forms of practice, like practicing the piano, or practicing being a nice person? What makes psychedelics a “practice” and not just a trip? Are practices “tools” or something more transformative? Many spiritual teachings stress the central importance of practice, but they rarely make room for practitioners to individually and collaboratively reflect on the sometimes difficult issues that arise around practice—issues like commitment, belief, guilt, obsession, intuition, experimentation, trust. We will also talk about ways to craft practices of one’s own, and to further dedicate ourselves to our existing regimens. Suggested donation, $30-60, no one turned away. Registration here.

• The Chalice, the Alembic’s monthly psychedelic salon, is opening the year with a bang. On Wednesday, January 8th at 7pm. Christian, Maria, and I welcome Michael and Carol Randall from the legendary Brotherhood of Eternal Love, the notorious “hippie mafia” centered in Southern California that trafficked hashish, Hawaiian cannabis, and LSD through the 60s and 70s. But the Brotherhood was also a registered non-profit religious organization founded in 1966, with LSD as its sacrament. Their mission: turn on the world and achieve universal peace through cosmic mind expansion. The Brotherhood helped plan Timothy Leary’s unsuccessful 1969 campaign for governor and created an international LSD network with its own secret laboratories, giving away more than 100 million doses of Orange Sunshine. In August 1972, federal drug agents finally busted the Brotherhood. Michael, Carol and their kids spent the next 12 years on the run before Michael was finally arrested in 1984 and sent to prison for five years. Today they are unrepentant models of grounded acid mysticism, as well as great storytellers with an unbeatable combination of wisdom and humor. Register here.

Appearances

• Blotter: the Untold Story of an Acid Medium was long-listed for the Non-Obvious Book Awards. Not as ego-gratifying as getting on the Short List, let alone winning one of the awards, but still an excuse for a smile. The book is definitely not obvious!

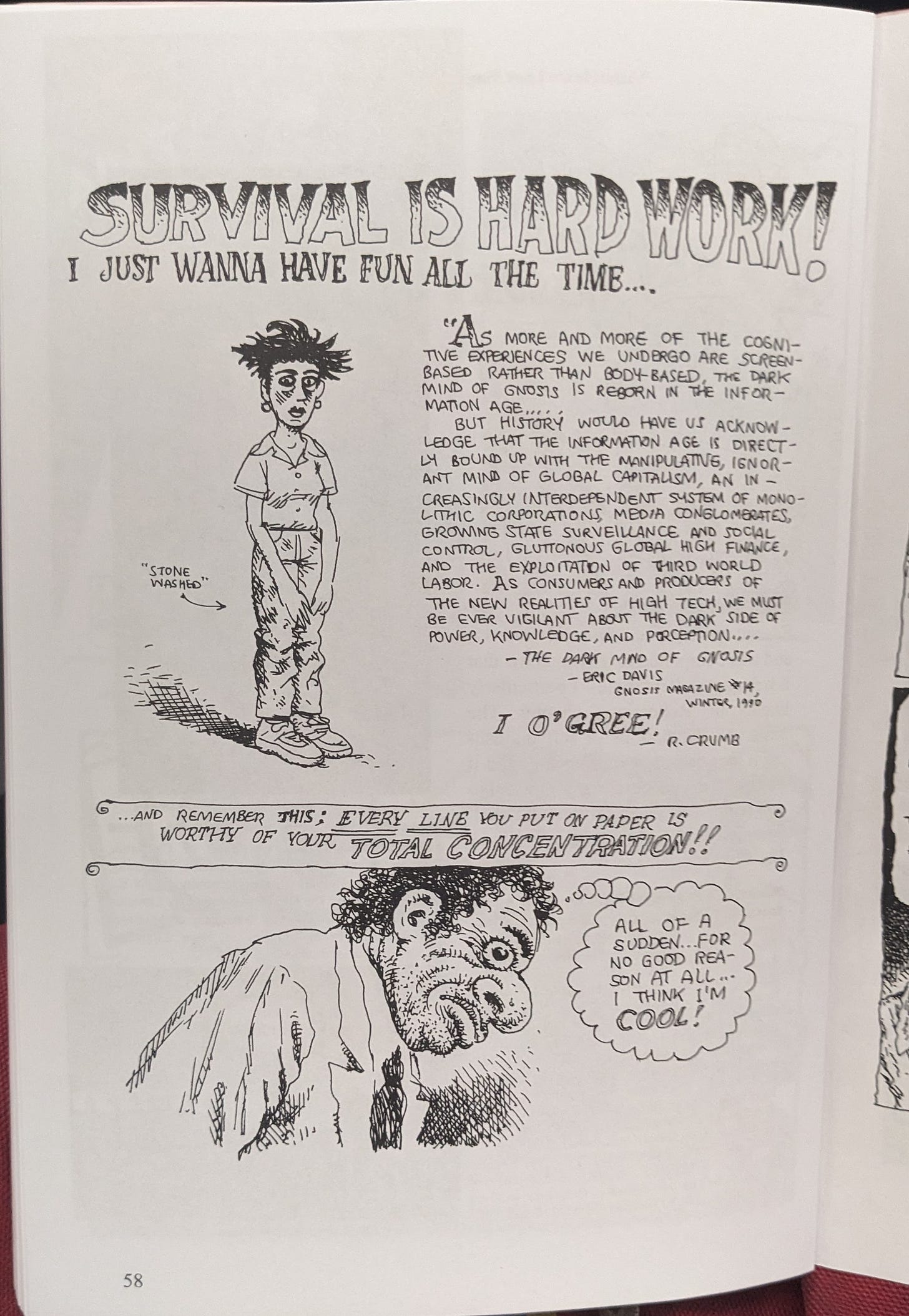

• Burning Shore pal Jesse Jarnow just let me know that, in the recent edition of Mineshaft, the legendary R. Crumb quoted an old Gnosis magazine piece I wrote many many moons ago. Given the role Crumb’s work has played in my subcultural imagination, especially his illustration of PKD’s “religious experience”, I was immensely pleased, and even forgive him the dreaded misspelling of my first name. I have no idea how he found this piece at this late date, which is not on Techgnosis.com or the wider Internet, as far as I can see. The piece shows how the dark side of the “gnostic mind” both damns and illuminates aspects of the modern world. Reading this passage now a quarter century later, it suggests that one of the reasons that Techgnosis and other essays of mine seem “prophetic” is that I balanced my attraction to expansive views with a critical edge, as the above post hopefully illustrates!

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. If you want to support my work, you are encouraged to consider a paid subscription. You can also support the publication by forwarding Burning Shore to friends and colleagues, or by dropping an appreciation in my Tip Jar.