Creative Imagination and the Inklings

I was raised without belief, but I’ve always been attracted to religions, to the luminous icons, the bric-a-brac of ritual, the lore, the architecture, the mysterious emotions of passionate believers. For quite a while I considered myself a seeker, and lodged time in Zen monasteries, Hare Krishna temples, New Age retreat centers, shamanic circles and, when I was much younger, a Bible study led by a fiery born-again surfer. But I am an unredeemably independent mind, too readily drawn to juxtapositions and contradictions to ever find anything, I suspect, like a Way. Or, more positively said, my way is with such wrangling—this wrestling with angels who occasionally embrace me or give me a knowing wink before knocking my ass into the void one more time.

I have also begun to suspect that, a lot of the time, what has really attracted me to religion was less the glimmer of supernatural knowledge, of some answer to the irascible longing in my heart and the mercurial confusion in my mind, than the creative imagination that channels so much of this stuff in the first place. At root, my spirit resonates with to aesthetic dimension of religion—the pungent bite of frankincense, the swelling gallop of Mozart’s requiem mass, the comic book arcana of cosmological maps, the turn of phrase in a lost gospel, the spare decor of the zendo. It is not that I am interested only in aesthetics, or story, or figurative art—I have spent tons of time with doctrine and history, and I love the experience of some model or argument about the nature of existence or God or the afterlife worms its way into my quotidian mind.

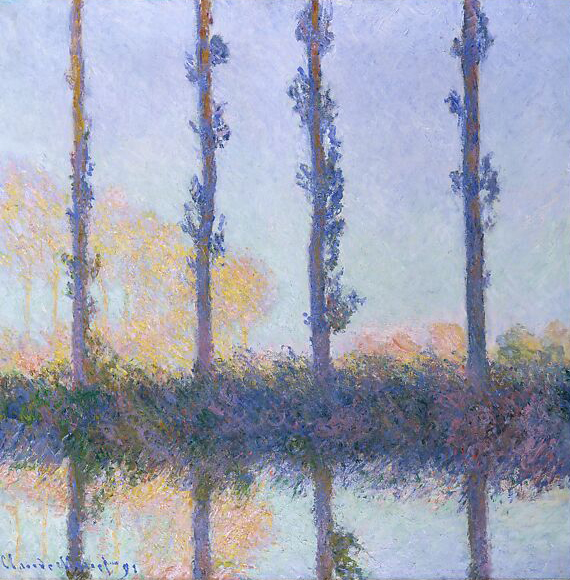

But the real alchemy happens when the creative imagination soars beyond itself, towards matters of final import. I cannot imagine an awakened genuine religion without flavor and taste, without vivid figures and surprise. I rarely read wisdom books unless they are engaging as literature. I’d say I was an “aesthetic seeker,” except that’s a lame phrase. It’s a way of connecting to the outer and inner realms through sensibility, both mine and others’, through a combination of feeling and recognition and intuition that art alone or philosophy or “metaphysics” alone cannot touch. Besides intensifying my interest in, say, Gothic architecture or the literature of Northern paganism, this seeking sensibility also intensifies my general reaction to the marvels (and terrors) of the world, so that I sometimes sense flashes of deeper being whether I am reading Wallace Stevens or mooning over pretty women or facing the future with fear. The Gnostics believed that shards of light are distributed throughout creation, and I see no reason to shut the door at our most profane pleasures and anxieties. Angels everywhere.

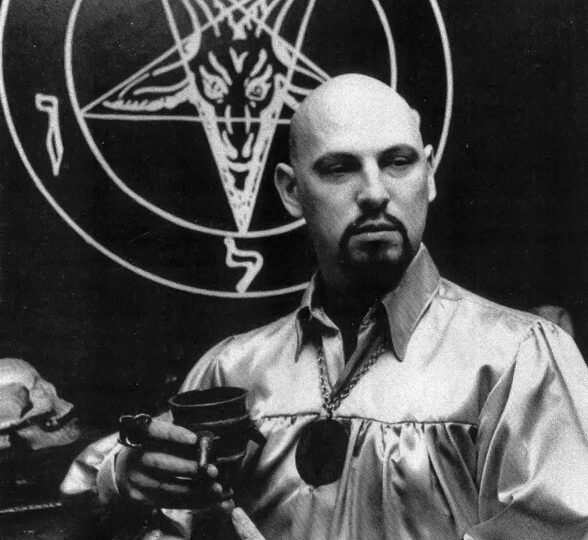

This partly explains why I have long been fascinated with artists who make sacred plays, whether—to take recent obsessions—its Oliver Messiaen’s mystic Catholicism, or Kandinsky’s Theosophy, or Rudy Wurlitzer’s Buddhism, or Deathspell Omega’s high-church Satanism. All of which helps to explain the alacrity with which I recently grabbed up an old cloth edition of R. J. Reilly’s book Romantic Religion from the shelves of Fields, which is hands-down my favorite metaphysical bookstore. Fields, along with Rainbow Grocery, Corona Heights, Amoeba, Swan Oyster Depot, and the Castro Theatre, is one of the reasons I still love San Francisco despite the fact that its well on its way to being the first fully gentrified city in America. The shelves were looking a little thin a few years ago, but the store has turned around, and has recently teamed up with Todd Pratum, a major dealer of esoterica whose witty and opinionated catalogs are as fascinating as most of their contents. So the shelves are now packed to the gills with musty delights, including this handsome yellow edition of Reilly’s book, which is subtitled A Study of Barfield, Lewis, Williams, and Tolkien.

There are tons of books about the Inklings these days, the informal Oxford group of fantasy writers, Christians, and beer guzzlers whose most famous members were C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Charles Williams, all of whom wrote enchanted fiction as well as serious literary studies. Though he never mentions the term Inkling, Reilly’s 1971 book is often reckoned as one of the best about these figures. Reilly’s central argument is that, as shown in different ways by all four writers, Romanticism, as both an aesthetic sensibility and a theory of the creative imagination, becomes a portal into religious sensibility—in this case, into Christianity. While the book left me no less troubled by the demonizing tendencies of orthodox Christianity (every time Reilly mentions the “enemy” I realized that despite my attraction to esoteric Christianity I am, in Blake’s phrase, of the devil’s party), Reilly’s study was a clear, intelligent, and keenly feeling affirmation of the redemptive potential of the imagination.

I am a pretty huge Tolkien fan, and his “On Fairy Stories” lies at the root of my understanding of why I continue to love and read fantasy. Tolkien’s famous line—“we make still by the law in which we’re made”—is one of those nifty “as above so below” hermetic echoes, only applied theologically, aligning the creative imagination with God’s primary Creation. But what Reilly really let me see again was how the fantasy stories Tolkien discusses—and created in The Lord of the Rings—offers what the don calls “Recovery.” First off, Tolkien makes a beautiful argument about escapism that all fans of “escapist” fare (fantasy, SF, role-playing games, even, uh, religious and New Age books) should slip into their quivers.

Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls?

Moreover, Tolkien argues, genuine fantasy does not so much let us escape reality as actually mend our relations with reality. How? By re-enchanting all-too-familiar aspects of life, from sunsets to the idea of heroism, fantasy can refresh our perception of the actual world, so easily cloaked in the drabs of failure and repetition. Isn’t this how eroticism works among lovers who know each other too well? Isn’t this the great, albeit tricky gift of cannabis? This is how the imagination creates “beginner’s mind,” an attitude that is arguably closer to always-changing reality than the resigned knowingness that adulthood so insidiously breeds?

I liked reading about Charles Williams, whose occult fictions I have never read and now have to. Reilly concentrates on Williams’ ideas about erotic romance as a mode of the Affirmative Way of celebration, a taste of beatitude, ideas he drew, with some elaboration, from Dante’s vision of Beatrice. In critiquing this stuff, Reilly comes off as a bit of a stuff-shirt, and this devil’s partier remains on the side of those who find in both the longing and the carnal bliss the lineaments of invisible powers. Moreover: the erotic spell can also inspire a fidelity that itself is only the prerequisite for an even longer and more luscious spell capable of spilling outside the boundaries of the relationship itself. As Reilly puts it:

The Beatrician vision is a ‘way of return to blissful knowledge of all things. But this was not sufficient; there had to be a new self to go on the new way.’ The lover for a moment sees the world as it is; then becomes his duty to go on acting as if the vision remained with him, even though it does not.

The most surprising and informative aspect of Reilly’s book was his discussion of the little-known Owen Barfield, whose more esoteric and penetrating ideas about the romantic imagination and the evolution of consciousness are so nifty I’m going to read his classic Saving the Appearances and post on it later. I’ll close instead with Reilly’s discussion of Lewis, a complex figure. I read Lewis’s apologetics in high school the way I read Chesterton’s today, and I never had much use for his fiction, with one significant exception. Till We Have Faces, Lewis’ retelling of Apuleius’s story about Psyche and Eros is a masterpiece of myth-making, written in awareness of both the limits of myth and the limitations we moderns impose on myth. Reilly’s discussion of the book is great, but not as great as his framing of Lewis’ core idea of Joy, of joyful longing, or Sehnsucht: the feeling of desire for far-off islands, for the enchantments that glimmer in childhood memory, for worlds beyond the fields we know. In a nutshell, Lewis believed that this essential emotion, without which the reading of fantasy would be a waste of time, opens into a longing for heaven. And though I cannot cross that river, at least in any orthodox way, I do believe this longing takes us directly to that liminal zone between the satyr’s glade and the temple, a place that is created by the presences that move through it without being contained by it.

After finishing Reilly’s book, I looked Sehnsucht up on Wikipedia, and discovered an unusually satisfying entry. For one thing, it included this killer Lewis quotation, one of the most insightful things I have read about the productive lack within desire, or at least the sort of imaginative desire stirred by landscape, or infatuation, or the tickling half-memories of childhood. This is imaginal tantra:

In speaking of this desire for our own far-off country, which we find in ourselves even now, I feel a certain shyness. I am almost committing an indecency. I am trying to rip open the inconsolable secret in each one of you—the secret which hurts so much that you take your revenge on it by calling it names like Nostalgia and Romanticism and Adolescence; the secret also which pierces with such sweetness that when, in very intimate conversation, the mention of it becomes imminent, we grow awkward and affect to laugh at ourselves; the secret we cannot hide and cannot tell, though we desire to do both. We cannot tell it because it is a desire for something that has never actually appeared in our experience. We cannot hide it because our experience is constantly suggesting it, and we betray ourselves like lovers at the mention of a name. Our commonest expedient is to call it beauty and behave as if that had settled the matter. Wordsworth’s expedient was to identify it with certain moments in his own past. But all this is a cheat. If Wordsworth had gone back to those moments in the past, he would not have found the thing itself, but only the reminder of it; what he remembered would turn out to be itself a remembering. The books or the music in which we thought the beauty was located will betray us if we trust to them; it was not in them, it only came through them, and what came through them was longing. These things—the beauty, the memory of our own past—are good images of what we really desire; but if they are mistaken for the thing itself they turn into dumb idols, breaking the hearts of their worshippers. For they are not the thing itself; they are only the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have never yet visited.

So keep sniffing, folks, keep your ears bent to the piping on the wind, keep your antennae up for news of the far country. It might turn out to be closer than you think, like Jesus says in the heretical Gospel of Thomas: “the Father’s kingdom is spread out upon the earth, and people don’t see it.” And if we never see it, if the big fairy-tale teller never lets down his cloaking device, then the longing at least keeps you keen.