Post-Apocalypto 1

Since reading Cormac McCarthy’s The Road back a spell, I have been lurching—in rags, without grub, through noxious, stinking piles of irradiated carcasses—through other works of post-apocalyptic literature. First up was Rudy Wurlitzer’s experimental 1970 novel Flats, an exhausted marvel that was reissued about a decade ago by Serpents Tail. Everything has been blasted in this book—not just the land, but the characters, even subjectivity itself. All the aimless wrecks who populate the “story” shuffle through degraded forms of social intercourse in the flats outside some unnamed ruin of a city. They name themselves after U.S. cities, as if the proper names of places whose differences no longer matter are the only way that remains to orient the self, or the confused, zombie-like existential tropisms the self has been reduced to. The narrator, for example, keeps switching between first and third person. As if that weren’t enough, the name of this third person itself changes—Witchita, then Mobile, etc.as the narrator picks up new identities and then watches, passively or with irritation, as they run themselves aground or simple fall apart.

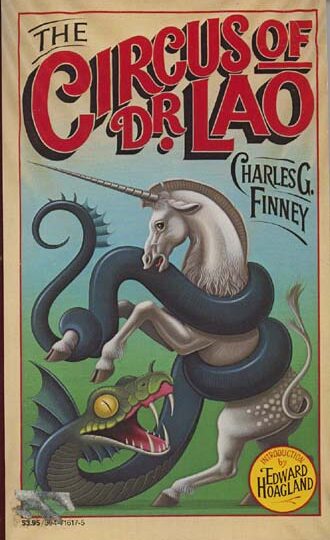

The true apocalypse in Flats is the implosion of the human person. Without nostalgia, Wurlitzer submits the self, the flimsy cell of modern consciousness, to entropy. And why not? Don’t you tire of yours, with its endless schemes, plans, and narcissistic fantasies? “The first person,” the narrator writes, “is driving my nose closer and closer to my own asshole.” So divide the first person. Earlier, in his debut Nog—a masterpiece that reads like Beckett by way of Richard Brautigan and the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers—Wurlitzer invokes a character who has gone so far out that he has seemingly dissolved all agency or purposeful action, a wayward knight long past the grail, pushing the edges of language in a world of beach bums and communes and freaky ghost towns.

All Wurlitzer’s early fictions are marked by this sense of drift, an aimlessness, once ascetic and funny, that also infuses Two Lane Blacktop, the exceptional 1971 film he wrote for Monte Hellman. Here is a characteristic passage from Flats:

There is just enough happening. The space behind me comes from everything I’ve learned or failed to learn. We all want to move out, to imprint an image on another space. But there has been nothing established. There has been no adventure. Thank god. We are saved an adventure.

Readers are saved an adventure as well, and must submit themselves to the minor tribultion of plowing through a plotless fiction that’s so beyond emotional engagement as to make despair no more an option that celebration. But Wurlitzer’s literature of evacuation also has a spiritual dimension, one devoid of myth or hope:

There is nothing to observe. There is only the light to receive. There is nothing to choose. I have all there is. There is nothing to go toward. I am that direction.

As a once-countercultural guy interested in the dissolution of the self, Wurlitzer has, not surprisingly, long been drawn to Buddhist practice and thought. He penned the screenplay for Little Buddha, wrote a small and bracing spiritual memoir called Hard Travel to Sacred Places, and begins his upcoming novela mystical western yarn called The Drop Edge of Yonder, that I’ll soon review for Bookforumwith a quote from the Lankavantara Sutra. Wurlitzer is done waiting for God(ot). His post-apocalyptic voids remind me of Bodhidharma’s boundless response to the emperor’s query: what is the first principle of the dharma? “Vast emptiness,” replies the barbarian. “Nothing holy.”