The Arthur magazine interview

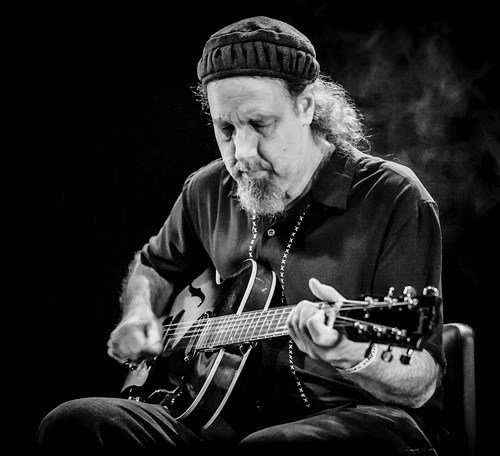

Superlatives can be lame, but Richard Bishop is one of the few post-punk guitarists who came of age in the 1980s to have achieved the incendiary prowess of a true Guitar God. Though largely unknown outside the underground, Bishop plays and improvises with an uncommon and original power. He can tantalize in a myriad of styles, he has a global juke box in his head, he can shatter the walls of sleep and chaos, and he can turn on a dime. He loves the guitar and mocks it: he plays like an absurdist and a romantic at once. He studies the occult and travels the Third World fringe and you can hear it. He plays guitar to save himself and fails in the endeavor and you can hear it. He can scare the shit out of you sometimes, and he can make you giggle and grin.

For decades Bishop played with his brother Alan and the Charlie Gocher in the Sun City Girls, where his ferocious and inventive exploration of psych-rock, punk spew, idiot jizz, Indo-Arabic fantasias, and jazzbo abstraction was often shadowed by the madcap antics, acerbic lyrics and general air of arcane weirdness that surrounded that impossible act. Gocher passed away in February this year at the age of 54, and the Girls are no more.

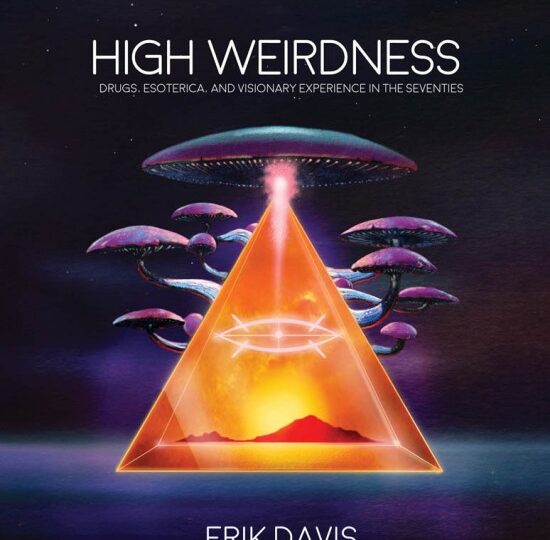

But over the last half decade, Bishop has also been playing and recording solo instrumental music as Sir Richard Bishop, and the effort is really starting to flower. This year SRB released two great albums. While My Guitar Gently Bleeds features three long pieces that triangulate his essential territory as an improviser: a North African arabesque, a noisy electronic nightscape, and a modal neo-raga on the tantric tip. Polytheistic Fragments is a more accessible and varied work, featuring a dozen tunes that also stretch into Americana, gypsy rag, and Lennon-McCartney charm. As always, the recordings are packaged with strange and mystic images that speak to Bishop’s longtime study of esoterica.

Earlier this fall Bishop toured with label-mate Bill Callahan. I called him while he was taking a break in Seattle.

ED: Before this tour started you spent the summer in India.

SRB: I spent the first week in Calcutta, then about a week in Assam, and then a little over two months in Varanasi. The idea was to make a quick trip and put some of Charlie’s ashes in the Ganges then head back to West Bengal. But there were all these serious floods, the train systems were all messed up, so I stayed in Varanasi.

ED: How was that?

SRB: It was quite comfortable. After the first weeks of constant hassle, people started leaving me along. I got into the flow of the river, and the life on the rooftops. I got a feel for how it would be to live there.

ED: I know you have been thinking about moving to Asia.

SRB: Well I’m starting to make a living as a musician now. It’s only taken 27 years. But the day to day living in this country just wipes stuff out immediately. Money there can last three to four times longer, if not more, and in a more interesting environment.

ED: What’s the downside?

SRB: You have to leave your friends. Plus you have to get rid of stuff. I’m just gonna take a guitar and what I need. You gotta be mobile these days—it’s coming down baby!

ED: You also went to some tantric temple festival in Assam.

SRB: The temple is called Kamakhya, and it is a shaktipitha. You know, Vishnu cut Shiva’s wife Sati into pieces and scattered the parts, and each place they landed became a pilgrimage site, a pitha. Kamakhya is the yoni temple, which is obviously the most sacred. It’s not just a big toe or anything.

ED: Is that the one with that ferrous flow of yoni juice?

SRB: Yeah. There’s a stone yoni shrine underneath the temple in a cave, and there’s a natural spring that bubbles up all the time. During the festival period—no pun intended—the water turns red. It could be iron oxide. Other folks think the temple priests add a little something to the water just to spice it up.

ED: What was the festival like?

SRB: It was a really weird vibe. I was the only white person for miles. There were a few people who were kinda friendly and would smile on occasion, but an hour later they acted like they never met me and didn’t want to have anything to do to me. They were really negative and then playful and then back again. I thought: What am I doing here? Do these people want to hurt me? Were they mirroring the different energies and aspect of the goddess herself?

What was most exciting were all the women priestesses who were there, Kali priestesses, yoginis. You’re used to seeing dreadlocked dudes and creepy sadhus everywhere, but these women sadhus were really refreshing. It reinforced the idea that this place is the historical center of witchcraft and dark art and tantric ritual. Everyone was dressed in red. It was spectacular.

ED: What is your attitude when you visit heavy tantric temples?

SRB: I go in with confidence. Of course I respect the customs, but I go in with the idea that I’m supposed to be there. That’s not always the right approach. There’s gonna be times where people or things or gods or goddesses are gonna put up roadblocks. That’s part of the fun. Whether its an initiation or just education, nothing comes easy.

ED: Many of your most expansive solo tunes are ragas named after Hindu goddesses. What is your attitude towards those deities when you play?

SRB: Its very subtle. The inspiration comes from my studies or travels, but I can’t directly transpose my experiences into my music, especially with a solo guitar. It’s more the energy of the experience and the study, and the feelings that come through. If I name a certain title after a goddess, it means I was at least thinking about that goddess while recording it. I don’t name them after the fact like I do with a lot of my songs.

ED: So what is your intention with these tunes?

SRB: It’s my way of giving back to the source of the inspiration. Whether people get it is not really important. It makes me feel good that I get it and that I’m giving it back. And it keeps the listeners guessing. I get a lot of questions like this. Usually I just give em a bullshit answer, much like I just gave you.

ED: Well, even if people don’t get the esoteric stuff, your playing sometimes sounds like an invocation.

SRB: What I try to do is when I play is to create an atmosphere, almost tell a story without words. If I’m playing a North African piece, I’m visualizing the desert and the Beduins riding their camels or whatever. Same thing with the Indian music. I’m talking about those environments without using words.

ED: That’s funny. I was listening to one song on your new record and I got a very strong image of devilish little skeletons dancing in my head. Only afterwards did I see the title: “Cemetery Games.” What’s up with that?

SRB: Ha. When I listened to that track back in studio, before it had a name, I had this vision of those Ray Harryhausen skeletons dancing around like in Jason and the Argonauts, not necessarily in an evil way, just having fun. The piece was gonna be called “Funeral Games” but I realized it took place long after the funeral. Just a happy skeletal dance, what they do when nobody’s looking, but dark enough so you could imagine it at night.

ED: For me, real magic has always been about the imagination, about creating and projecting powerful images. Are you conscious of making music that is good for visualization?

SRB: More so in the past with the band. That played an important role sometimes in the mid to late ‘80s and early ‘90s, when I was really into Crowley thing, the dark, icky thing. Now I’m not trying to do anything in terms of the listener. If it works for me that’s all I care about. People will have their own take on it.

ED: A lot of the imagery and vibes of Sun City Girls stuff clusters around death. So what happens when the real thing shows up?

SRB: I’ve been OK with death for a long time. I started off studying Egyptology, where death is so important. It’s the beginning rather than the end. Death as a necessary transformation. But when you’re dealing with the death of parents or friends, when you’re watching somebody die, its really kind of a drag. Death is in the room, and its like, You fucker.

ED: Then what?

SRB: Once its over its not so hard. You’re like, Lucky them. They made it to the finish line first. They’re celebrating their victory. I mean, I’ve already considered where I’m going afterwards. I’m not telling anyone, but I got plans.

ED: How did Charlie deal with dying?

SRB: Before he passed away, we talked, and he said, “Looks like I’m gonna be experiencing things before you guys.” It was a serious conversation but it was also light hearted and somewhat humorous. Deep down inside he was most likely facing fear, but knowing that he was also comfortable dealing with it that way helped me deal with it.

ED: So who was Mr. Charlie Gocher?

SRB: Charlie was a magician of the highest order though he might never have admitted it or acknowledged it. He was perhaps the most mysterious being I’ve encountered in all my time on this and other planets. And though Alan and I knew him better than anyone else, I don’t think we ever really knew him. And I’m sure he designed it that way.

ED: How did he change you musically?

SRB: When Charlie joined up with us, a whole new series of galaxies opened up for exploration. At that time I was still muddled in the finite worlds of punk, heavy metal, and classic rock. He exposed me to free jazz, bebop and the Beat generation.

What a lot of people may not know is that he was also an exceptional guitar player. Whenever I watched him play guitar it was so frustrating because, first of all, he was so good at it. And secondly, he played left-handed on a right-handed guitar and I could never figure out how to play what he was playing.

But most of all he was a fantastic writer, a master of the English language and also of languages that only he understood, and perhaps invented. Over the years we’ve preserved boxes of his journals and writings just so they wouldn’t be lost. And when he passed on, we found more boxes of his work. Reading through just a fraction so far, the mystery just deepens. He was one of the great ones!

ED: Now that the Sun City Girls are behind you, can you tell me who or what the fuck they were?

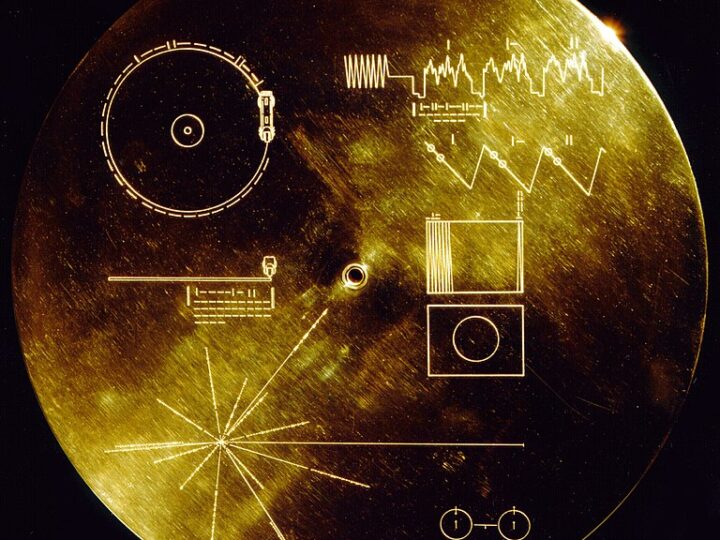

SRB: This is a tough one…I guess I could say that Sun City Girls were three rough and ready individuals, each with their own unique musical talents that worked well enough on their own but when combined together formed something far greater. We were a band and somewhat of an “anti-band.” Since the first time we all played together, at an open mic night in 1981, we were somehow led to an approach to making music that was beyond borders, barriers, and boundaries. Each musical idea became like a work of art hanging on a wall, but without a frame around it, allowing it to roam freely around the wall and the room, continuing ever outward into unexplored realms and never just confined to a single space.

ED: You also had that punk rock attitude of not giving a shit about what other people made of it all.

SRB: We were never a group that worried at all about public opinion or acceptance. Each song or record was designed to be interpreted and understood by those who were equipped to do so, and to be shrugged off or shunned by those who didn’t like it or who couldn’t–or wouldn’t–comprehend it.

Over the years we became increasingly confident with this way of working. We were able to build this machine that seemed to run itself after a while. It was alive. It had a presence: a powerful force and at times a farce. But a farce to be reckoned with!

ED: Ow.

SRB: The most important thing was that we took chances all the time, and enjoyed doing so. That was how we kept ourselves interested: constantly pushing ourselves into new situations and directions. It’s great to surprise yourself!

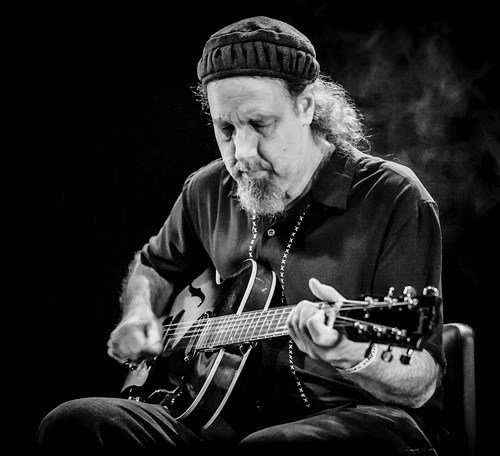

ED: You can certainly hear that surprise and pleasure in your acoustic recordings, which are mostly improvisation. How does it change when you take those tunes on the road?

SRB: Well, I’ll do the same sort of song every night, but with all those songs, there’s this open space that I’ll have to fill in with different improvisations, knowing that I’m eventually going to go to a certain place. But now those songs that used to have a lot of space have closed up because I’ve filled those spaces so often with things that work. So now those songs are finished, and I’m done with them. I’m sick of playing them. It’s a little frustrating actually.

ED: So what are you gonna do?

SRB: Next tour I’m going to try to do all new material. Step away from that repertoire and just try something else off the cuff. Don’t worry about whether its good or bad, just try to force myself into a situation where improvisation is going to have to come back in. I might even bring electric because that might be the only thing that forces me to evolve.

ED: A lot of folks mistake your guitar playing for finger-picking.

SRB: I am never not using a pick, though sometimes I’m using my fingers as well. I’m terrible at finger-picking, and I have no intention of learning at this time in my career.

ED: What the hell is that pick you use? It looks like a goat vertebrae or something.

SRB: It’s a real fat pick made out of some strange plastic by a guy in the Netherlands named Michael Wegen. Gypsy guitar players in the ‘40s and ‘50s often used picks of that thickness, only they weren’t picks. They would use things like pea coat buttons. That helped them develop those chunka chunka rhythms, that gypsy backbeat. I tried using a Fender heavy pick the other day and it was like a piece of cardboard.

ED: On your last couple of records you have been using gypsy guitars as well, with that loud, bright tone. How did that come about?

SRB: It happened by accident. I started playing those guitars only a few years ago because I wanted to master the gypsy sound. That got old for me really quick. I went to a Django festival, which was just a collection of fucking guitar geeks. God bless ‘em, but if they don’t play the solo on the 1947 version of “Dark Eyes” exactly note for note then they feel like they’re not doing their job. I didn’t want to be like that. It left a poor taste in my mouth. Then it turned out that the tone of that guitar went really well with North African music and Indian ragas. So I just took that gypsy style and applied it to what I was already doing with the African or Hindu stuff.

ED: You get a lot of volume out of that guitar, but you are still opening for rock bands in rock clubs. What’s that like?

SRB: When I started the solo thing I was playing shows with really loud bands like Sunn O))) and the Dead C, and here I was with my little acoustic guitar. You wonder if you’re gonna catch the audience’s attention for five minutes. Its not easy. It’s nerve wracking. But my experience of playing music is different than most people. I mean, I grew up playing in the Sun City Girls. I’m used to audience heckling and not pleasing an audience. So I’m like, I’m just gonna play because I know how to play.

Now I kinda like it when I play in front of a crowd that has no idea who I am or what I’m doing. Usually by the end of the set a good majority of the crowd is into it. And even if they aren’t, that’s just my job now. It’s a lonely feeling up there. But I have invisible friends and they’re all around me. I’m never really alone.