Voivod’s Schizometal

Every serious rock fan should sell records sometime. Me, I spent a summer trapped behind the register of Harvard Square’s Newbury Comics, a loud indie-rock version of Tower Records. I’d always watch the metalheads who snuck in, out of place, sullen and withdrawn, boys with pimples and old steely sweat. No glam for these rejects who trained in from the subs—they bought thrash. The strangest creature was a thin, light haired kid who hobbled in every other week with a cane and a cool sneer. Nearly blind, he would approach the counter and demand his desire, the new Overkill or Venom or Discharge. My attempts at conversation failed. He just wanted software.

Don’t be fooled by MTV or K-Rock: the secret history of heavy metal is the interior life, the solipsism of power, the danger of being 14, alone, and thinking very strange, very fucked-up thoughts. Dangerous Toys’ current video “Scared,” is brilliant not only because it’s badboy metal referencing demon metal but because it points to the context of heavy metal consumption: the dark, claustrophobic suburban room far from Hollywood, the locus of both alienation and the libidinal froth of teen dementia. Lost in the dungeon of his headphones, the kid makes scorpions and spiders breed. Voivod go to this place in their new “Into My Hypercube:” “In my dome, on my own / a locked thought in a closet /…dank angles in the attic, sixth sense stockpiled in the cellar / and the ladder is broken.”

This sentiment links metal and ’70s progressive rock, music that took advantage of rock’s ability to go somewhere else, even if that place was overblown and unreal. Prophecy: the most vital rock of the 90s will come from some perversion of the metal camp, because the only direction to go from the tiresome, fashion-mag surface of phallocentric metal is towards complexity, and because mere power chords can’t do it anymore than college-rock aimlessness. Voivod, King’s X, Faith No More, Watchtower, Nirvana, and Coroner are bands that quaffed deep on the ’70s and tasted not only fuzzy chunks but principles of composition. Not that (sm)artiness or the cult of technique will garner metal much respect, especially given that damning marketing profile: white, male teens.

Interesting thing about that marketing slot: it’s the same one that spawns hackers, phreakers, and computer-game fanatics. Hmmm. No claims are made about innate capacities or purities: this is a social formation we’ve stumbled on. It could be nothing other than a love of cheap thrills in the absence of three-dimensional females, but teenage boys are most infected with the culture of computers, the confusion of the VDT’s fantastic realism with the shapes of interior life. They like metal. Thrash heads fight data with data, transform their alienation from the tyranny of the image into a love of systems, and turn towards the most immediate technologies—headphones, computers, brain drugs—to exit within. That kid in Cloneville, headbanging to Metallica and clacking away at the screen, knows that power and movement is psychic thing, and that guitar distortion is the texture of the machine that surrounds.

***

If we can talk about “terminal films” (Blade Runner, Alien, Robocop, Fassbinder’s Kamikaze ’89, Atom Egoyan’s Family Viewing and Speaking Parts), then Voivod may be our first terminal band. Outside of P-Funk, there is no better science fiction band, no one capable of spewing the line “I float unseen outside the screen” and meaning it. Unlike so many pale-faced postmoderns, they don’t use the machine to produce music that sounds like a symptom of the machine (a la Wax Trax). Their machines are aesthetic Others, entities that mix their alien logic with the shapes of the human mind, fractured and fragmented through fiber optics and the psychic mirror of the monitor.

What do you say about a band obsessed with technology that doesn’t even own a sampler? Here’s some more unresolved contradictions: Francophones who sing in English; metalheads who play accordion; goofy, totally unpretentious guys who drop Bartk, Artaud, and the French counter-history of science Le Matin des Magiciens as influences (they love the word influence). Standing against a photo mural of gargoyles in Montreal’s rock club Foufounes Electriques (translation: electric butt-cheeks), I asked drummer Michel “Away” Langevin why he didn’t have any attitude. In his thick accent, he answered “What does it mean, this ‘attitude’?”

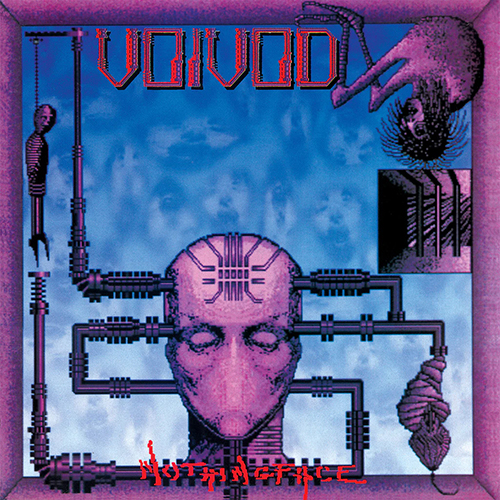

Musically, their beginnings are humble enough. 1984’s War and Pain was painful tar-rock, and RRRoooaaarrr an overload of sloppy thrash. As guitarist Denis “Piggy” D’Amour told me, “We just played way too fast. We were losing feeling. So we slowed down and got heavier.” Their transmutation began with Killing Technology in ’87 and continued on last year’s excellent Dimension: Hatröss. On Nothingface, the new one, they transcend thrash and play with space, suspense, silence, sheen. In some ways they’re jamming on a channel I always knew existed but could never find, a Fourier transform of the baroque beauty of early Iron Maiden, the overdrive of Judas Priest and Motörhead, the vision fuzz of Chrome, the density of mid-’70s King Crimson and Rush, the Euro ghosties of Peter Hammill and Bauhaus. In other ways, they’ve gone beyond known elements.

Nothingface is disjointed, even inconsistent at times, like a machine that wakes up one morning to find it’s evolved into something else. The bass and guitar are on equal footing, stretching the music between them like synthetic taffy, drawing constellations of alien harmonics and then scrambling the connections. Piggy plays intervals more than leads, skewed dissonant figures that brand Jean-Yves “Blacky” Thriault’s growling bass riffs like ghost circuitry. “I like to hear the distance between notes,” Piggy said, a little bashfully.

Inside these distances, Denis “Snake” Belanger inputs his lyric code, which splices together the language of technical manuals, Away’s “concepts”, philosophical jargon, schizophrenic desire, and clunky Latinates like “displaced,” “refracting” and “exclusion principle.” He chops up syllables (“cy-ber-net-ick be-ings”), stresses the wrong accents, mispronounces, misconstrues meaning. And having grown up on the bastard French of Quebecois (“It’s not French we speak, but slang — people from France can’t even understand us”), English presents a batch-code of sound as much as sense, and Snake teases words like freeze and choke as only a non-Saxon could.

In Voivod’s cover of Pink Floyd’s “Astronomy Dominé,” he rolls Syd Barrett’s internal rhymes around his mouth like pebbles: “Floating down the sound resounds around the icy waters underground.” MCA “urged” the band to release a cover as their first video-single, an increasingly familiar marketing trend that combines ancestor worship and the commodification of memory. Barrett is an appropriate old one, though Piggy told me he prefers the live version of the tune on Ummagumma, which he first heard when he was about 10, and his older freak cousin needed a soundtrack to fry to. “I heard that scream, you know, in ‘Careful With That Axe, Eugene’ and I thought, ‘Ah, that’s what taking drugs does to you.'” A few years later, Piggy was lost in the haze of Van Der Graaf Generator, slamming out the chord’s of Rush’s “Bastille Day,” and then switching to bass to learn Yes and Gentle Giant licks because they were too hard on guitar. Go ahead and wince, but these days he’s got metal’s best ear, and his band smokes hash with soldering guns.

L’HISTOIRE DE VOIVOD, pt. 1: He is spawned on the planet Morgoth, a barren planet wasted by the mega tonnage of thermonuclear war. The Voivod is an aggressive little beast that sucks the blood from mutant rats and inflicts pain. He transforms into Korgull the Exterminator, a war machine that roots out the few humans the remain burrowed in holes on the wasted plain. The Voivod then bags Morgoth and hits the big space-time as a laser-toting cyborg, before reading too much pop science and discovering the micro-worlds of particle physics and the flavorful psychic entities that lurk inside the atom. The Voivod makes money here and there, painting telephone booths, shaking down the government of Quebec for grant money, making metal records in Berlin and Montreal. In ’89, he loses his face.

Voivod was spawned in Jonquière, an isolated, frozen Francophone town of aluminum factories and paper mills 300 miles north of Montreal. Records had to be mail-ordered, English learned from Beatles lyrics and cable TV. Michel Langevin, Jean-Ives Theriault, and Denis D’ Amour went way back, but it was their deep and abiding love of Kiss that brought them together. They got the idea of forming a band, named it after Vlad Dracula’s army and a creature Michel liked to draw. Only D’Amour could play an instrument and no one wanted to sing.

In Quebec there is a game called Improvisation, played in a small arena surrounded by bleachers. Cards are randomly drawn, naming a theme and certain performance constraints. Teams or individuals then have to improv on the theme, sing it, act it out, joke it up. Galoshes are thrown at lousy players. The three Vois in search of a Vod went to a match where Denis Belanger was given the task of becoming a worm caught by the flashlight of a fisherman. He scrunched up his elastic face, put his arms inside his shirt, and crawled around the floor, and got penalized for cracking up. He also earned a nickname and an escape route from a life of aluminum and the threat of Alzheimer’s.

Isolation paid off. As Piggy said, “We wouldn’t be Voivod if we came from New York or L.A.” In Jonquière, they could choose their influences, engineering their infections while ignoring everything else. Despite taunts like “Forget it, you’re not from California,” the band moved to Montreal in 1985, an accessible city with a hint of European rot and a slogan “Je me souviens” whose subject no-one can remember. “We ate burned Kraft dinners for two years,” Away recalled. “We all looked like Kraft, Kraft bodies, a Kraft smile.”

“Ugly yellow tubes,” Blacky said.

Despite few venues, an antipathy towards metal, and an airtight and arid scene of rockers who sing in French and get subsidized by the government (!), Voivod stuck it out. Some Canadian Francophones looked down on bands who sing in English, but Voivod didn’t give a shit. They weren’t going to stay in the hole of Quebecois.

Besides, tonight, almost five years later, they’re performing on the Solidrock program of MusiquePlus, a French language spin-off of Toronto’s MuchMusic rock video cable channel. I’m stoked because I’m a stupid Yank writer who wants to put Voivod under the umbrella of some Canadian aesthetic, as if the existence of Canada’s immense, ancient and tangled cable networks caused this disparate land to produce such chill terminal visionaries as William Gibson, Marshall McLuhan, David Cronenberg, Atom Egoyan, and now Voivod. Solidrock host Paul Sarrasin, a short Tim Curry with better hair, is stoked because it’s Solidrock’s first live performance. A low-rent rigged camera swings like Tarzan into a singing Snake. Dry ice pours. Sarrasin grins from the empty beer-kegs they use as seats. Unlike MTV, the show’s truly live, and a couple hundred thousand Canucks tune in.

L’HISTOIRE DE VOIVOD, pt. 2: Voivod becomes Nothingface, turning inward into the hypercube of psychic solipsism. He kills his original personality because he thinks it’s too weak to face the future. He begins to fashion new selves, but realizes that they’re hopelessly fake and that they nauseate him. He reaches back for his original self but can’t find it, because it’s lost or shut out by a big machine, he can’t figure out which. He hovers in the circuitry of the machine, jammed between the corpse of his old self and the glistening synthetic cocoon of the new.

A hundred and fifty years before, a tawdry Parisian poet leans back in his chair, notices a strange, alien light in his glass of absinthe, and asks laquelle est la vrai, which is the real one?

The story of the Voivod is also the story of Away Langevin, Voivod’s drummer, graphic designer, and resident theorist. “I began to draw when I was about five, first drawing characters from the TV screen. Then I drew the things around me, but that got boring so I started drawing my own monsters in my room. I was seeing them and talking to them. And they were answering me. That’s where the Voivod was born.”

Welcome to the mind of a 13-year-old who shuts himself in his room and spends all his time drawing and reading SF and books about vampires and schizophrenia. “I began to realize that everybody has his own little dose of schizophrenia. Schizophrenic people were more human to me than regular people. They are like the mirror of what everybody’s trying to hide from, so they try to shut them up. I began to be really angry about that,” he said.

“My best friend when I was younger was shut out. I was about five or six and he was a year older. He was the one who really influenced me to create worlds from my drawings, because he was doing the same thing. To me he was a superior intelligence. He could remember so many details for his age, it was incredible. Someday when he was about seven or eight he became nothing, and the little guy who was always with him who was his imaginary friend became him. And he stopped thinking that he existed. He would act all day in the function that he was nothing and that the little guy was him. It was pretty weird. The family didn’t really accept it. At some point he began to shout that somebody hurt his friend—well his ‘him,’ you know, and he started to run after his sister with a knife. So they took him away to a special school.” Away pauses. “But he influenced me in a good way.”

L’HISTOIRE DE VOIVOD, pt. 3: In 1817, a gaunt and pale 17-year-old was found wandering into a German village speaking no language, having no awareness of the world or his personal history. Named Kasper Houser, it turned out that he had been locked alone in a castle cell his whole life, with no contact with other humans or the outside world. He may have been a prince being denied his inheritance, but before anyone could find out, he was stabbed to death.

When Away drew the cover for Nothingface, he was thinking of Kasper Houser as he sketched an image of himself, armless and scraggly haired, hanging upside-down from the upper-right corner of Nothingface’s cell. He tacked the printout together with red pins on his wall. Upon seeing the image, a film student friend of his recognized Kasper Houser immediately.

In his dark, messy room, Away’s PC clone sits next to a pile of Astronomy magazines, a copy of Carlos Castaneda, and a Yoda doll. He draws by hand, and rather than scanning the image into the computer, he just redraws and colors it with DPaint II tools. The results are dark pixel dreams reminiscent of the dense visions and alien scrawls of French comic artists like Moebius and Druillet. (Appropriately enough, Away is doing a Nothingface comic for Heavy Metal). Perhaps the best cover artist ever to be in a band, Away’s graphic edge points to the near future, when the most visionary groups will directly seize the image-making apparatus that already thoroughly penetrates popular music, becoming less of a “band” than a multi-media machine.

Because he uses only pirated software, Away has had lots of problems with his technology. “Sometimes my computer is sick because it’s been touched by viruses. All my programs are bootlegs, you know, so it’s easy to get them.” For a while he’d get ones that would disable his system and then flash a message telling where to send $20 to find out how to eradicate the problem. Then there was the one that flashed the message, “Something wonderful is happening: your computer is alive!” and his data got slurped. “You know, you can get disinfectant programs, but then they make new viruses that can’t be killed, and then more anti-virus programs. It’s crazy.”

Computer viruses have not been Voivod’s only run-in with beasties that come from within. In the summer of 88, it was discovered that Piggy had a tumor in the hypophysis gland behind his optic nerve. The thing had been there since about the time Voivod was formed. They canceled their tour and he spent a month in the hospital. “They catch it early enough,” Piggy said, “and they treat it by pills so the tumor will be melted, but I will have to take hormonal pills forever because my glands don’t work.”

“I felt responsible, maybe,” Snake said, chuckling. “He had a brain scan and I wrote the songs a year before [“Brain Scan” and “Ravenous Medicine”]. Life is strange, you don’t know where ideas are from, from the future, a déjà vu, or what.”

“But I created the concept!” Away burst in, laughing. “It’s my fault!”

***

There is no subject left in the Voivod, just a wired matrix of energies, connections being made just as you hear them. The band lunges into the future not by cataloguing its effects, but by coupling them with whatever is available: pseudo-science, low-rent computer graphics, false theories. They imagine the future by letting it imagine them. Sometimes I’ll even admit that Nothingface can be way too stilted, that Snake Belanger croaks some duds, that a handful of riffs are overbright, but only in passing moods. I hear the future in this shit, flowing backwards at me like frozen light. The philosopher’s stone is a silicon chip–dope as science, science as dope.