Charles Finney’s masterpiece of American fantasy

So a couple semi-secret hermenauts I know recently said that one of their favorite fantasy novels was Charles Finney’s The Circus of Dr. Lao, whose title and year of publication (1935) sent me to Amazon with alacrity. Though understandably obscure, the volume is in print from the Bison Frontiers of Imagination series, which features a number of more known (to me) heavies like David Lindsay, H.G. Wells, and M.P. Shiel. The new edition directly follows the original, so you get a nifty newspaper typeface and, best of all, demented Dr. Seuss illustrations from Boris Artzybasheff. The book went onto the usual pile, and it wasn’t until the Pilkdown Man, who was visiting from London, read it with fulsome praise it that I gobbled up the short tale in a few large draughts.

One of the great things about this book, which is now also one of my favorite fantasy novels, is that it is written in a wry, down-home, deeply American key. While the prose is sometimes enchanting, blooming into those high-toned poetic invocations of ancient myth and mystery required of all great fantasy, these paeans are often abruptly terminated into the sort of anecdotal deadpan Americana you associate with, I dunno, Will Rogers or Mencken at his less mean. Finney was a newspaper man in Arizona, and the texture of Depression-era small-town life, with its fools and quaint ideas of fun, is so knowingly crafted that when the erotic mysteries and perplexing chords of deep fantasy hit, it deepens the wonder by delimiting it, darkening it in demotic relief, making it genuinely weird.

The tale concerns that archetypical irruption of the archetypes into the flat expanse of everyday life: a mysterious circus comes to town. There is no real story as such—we follow a number of characters as they discover and then visit the circus, and their experiences are ours. Great attention is paid to the advertisement that announces the circus, and the subsequent main street parade that continues to drum up interest. During the parade we watch a variety of townsfolk react and, in particular, disagree about what they see. Is it a man or a bear in that wagon driven by an old Christ who may or may not be Apollonius of Tyana? Is the unicorn a fake? Here Finney evokes the ambiguity that is at the core of fantastic perception, its ability to divide perception against itself, and to clear the ground for something uncanny to arise.

Dr. Lao is described an “old Chinaman,” and while that description may set your racist pulp radar a quiver, Finney does something very peculiar and effective with the stereotype: he simultaneously indulges and subverts it. During the circus, Lao describes his menagerie of wonders, and these lectures—which demonstrate how wonder is a matter of language as well as object—are eloquent and deeply learned, and riven with dark and unspoken ironies. But when Lao has run-ins between the tents with cops or drunken college students, he reverts to Fu Manchu talk: “You no like this Gloddam show, you go somewhere else.”

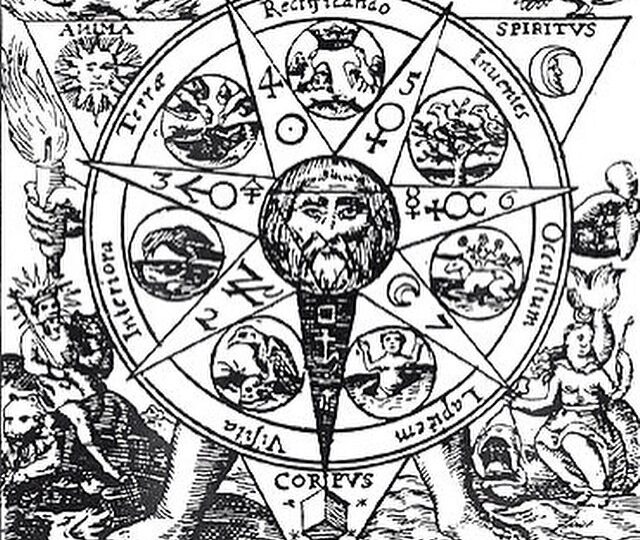

Many of the figures themselves—a sphinx, a satyr, a sea serpent, a chimera—are drawn from traditional lore, and from his description of the chimera alone, it is clear that Finney had access to a good library and a great Fortean imagination. The most evocative creature here is the faun, whose seduction of a prim schoolteacher vibrates with an unexpected pulp heat, a charge that returns in an even more excessive key when we visit the peep show, with its dusky African maidens and the arrival of a god named Mumbo Jumbo.

A number of creatures are freely invented, my favorite being the “hound of the hedges,” an Arcimboldo-worthy dog creature spontaneously generated of plant matter that Lao snared in North China, who drools chlorophyll and wags a tail made of ferns. Lao classes all these creatures as part of “an unbiological order” that Finney is clearly interested in characterizing life outside of law. Lau calls it unbiological “because it obeys none of the natural laws of hereditary and environmental change, pays no attention to the survival of the fittest, positively sneers at any attempt on the part of man to work out a rational life cycle, is possibly immortal, unquestionably immoral, evidences anabolism but not katabolism, ruts, spawns, and breeds but does not reproduce, lays no eggs, builds no nests, seeks but does not find, wanders but does not rest.”

The book ends with a very curious device I have never encountered before: “The Catalogue,” a twenty-page inventory and dramatis personæ of all the characters, creatures, objects, and gods in the story itself, with definitions and explanations that are alternately hilarious, engrossing, and so dry they turn to dust in your hands. Enjoy:

Frank Tull’s Stenographer: A commercial college graduate of the ovarian type.

Monk from Tibet: He lived in a yurt, ate tea thick with butter, wondered a lot about life, took a vow of chastity but broke it when he was in Alexandria, discovered the Ovis poli and the spectacled bear, not knowing what he had discovered, knew some good jokes, and died without every being really satisfied.

Gnats: Mother Nature’s tiniest flying machines.