The jungle in film

A few weeks ago, $2.99 at a Pizza Hut counter got you a FernGully: The Last Rainforest kid’s pizza pack: a single-topping Personal Pan pizza and beverage of your choice, a packet of seeds, and a bowl-shaped plastic terrarium vaguely reminiscent of Bruce Dern’s deep-space greenhouse in Silent Running. After slurping your Coke dry, you could fill the faerie-decorated cup with soil, plant the seeds, and slap the terrarium cup on top. You got a booklet too (“See the movie, plant the seed”), with an environmental quiz about recycling, a word search (“Ozone,” “FernGully,” “Green”), and a postcard with questions on it like, “If everybody pitches in, can we fix the environment?” If all this seems like typical marketing to you, just think what it means that all those Mutant Ninja fans are even given the option of saying: No, it’s too late, we can’t fix the environment.

Of course, the packaging is a waste, the food sucks, and the fast-food pepperoni is only one step away from the Whoppermeat we chop up the rainforest for in the first place. As ecological urgency spreads through the choked channels of pop culture, seeds of science will continue to be sown in cartoon packages. But only the pure can afford to attack such plastic paradoxes as useless hypocrisy, for if massive environmental consciousness-raising is what the greening of policy and lifestyle requires, then we have get our hands dirty, because consciousness is some messy shit. Information alone—documentaries, T-shirt slogans, MTV PSAs—will not solve the problem. It won’t even budge most data-saturated minds. As an advocacy science, ecology must not only convince. but seduce. Without images to rise toward, consciousness too often founders. Activists are figuring out that the bitter litany of irreversible devastation goes down better with the pitter-patter of shamanic drums in the background.

Besides, all science dons a mask as it enters the popular mind, given that it has usurped myth and religion as the primary vehicle of cosmic forces (Big Bang beginnings, computer-aided Terminator metamorphings, mushroom cloud endings). As a spate of recent films shows, the Amazonian rainforest has become the main visual icon of the environment we’re trying to save. Unlike the Sahara or the Himalayas, the rainforest is perceived not only as wild nature, but as an ecological space, the juiciest example of nature as a holistic system. Why? Moviegoers can tell you why—vast, dense and green, the rainforest looks like a living being. And the difference between its health and disease is not an invisible matter of water tables or atmospheric holes; it’s naked to the eye (or the camera). Even orbiting astronauts can see South America’s burning sores.

The Amazon embodies the founding tenet of environmentalism: everything is connected to everything else. This bottom line is as true for the forest’s networked ecology as it is for the economic and political forces that cause the destruction. Both nature and culture become entwined in one messy web of multinationals, carbon dioxide, Third World debt, gold, DNA, shamanic wisdom, hardwood, and Big Macs. Unfortunately, dynamic holism is tough to chop into straightforward narratives, let alone soundbites. So the greenness of movies like At Play in the Fields of the Lord, Medicine Man, Amazon, Meet the Applegates, and The Emerald Forest lies in their edges, the (literal) background: a bit of dialogue about oxygen, some representative characters, some trees. Even when Mika Kaörismaki’s Amazon puts the forest’s real-world politics into gritty forest, it fails to generate anything interesting, as a down-and-out Finn aimlessly passes through the jungle’s tawdry economies—mercury-poisoned gold digs, diamond mines, slashed forest, impoverished Indian villages. The urgency expressed in the epilogue — “at the present rate of destruction, this generation will witness the complete and final devastation of our planet’s most valuable natural resource” — is nowhere felt in the movie. The Finn’s pasty European soul remains unregenerate, the forest a mute curtain.

Other green films treat the rainforest as a more imaginative space, struggling not against gold miners but against the much older mythological tangle of the “jungle.” Interestingly, the ecological difference between these two spaces resonates with their mythologies—the rainforest’s cathedral of canopy and speckled darkness has interiority and ancient grace, whereas the chaotic, claustrophobic jungle that surrounds and penetrates old-growth forest is the tropical environment most Westerners carry in their dark hearts. The jungle: a space of ecological racism, an amalgam of colonialism, Joseph Conrad, Edgar Rice Burroughs, safaris, voodoo, and Vietnam. If the West fears and distrusts its own Mother Nature, it really demonizes the tropics.

Just listen to Werner Herzog go morose in Burden of Dreams, Les Blank’s documentary about the German filmmaker shooting Fitzcarraldo in the Amazon: “If I believed in the devil, I would say the devil is right here.” For Herzog’s European soul, the jungle means “fornication and asphyxiation and fighting for survival and growing and rotting away,” all of which makes for an “overwhelming lack of order—even the stars up here look like a mess.” Of course, the jungle expresses a most juicy kind of order, but even when Herzog acknowledges the ecosystem, he comes on like a paranoid monk: “There is some sort of harmony: it is the harmony of overwhelming and collective murder.”

Now we are in the heart of darkness, a place without clarity or purpose or space to define the limits of the Western individual. You lose yourself here, suffer apocalypse, or are swallowed up in native madness like Conrad’s (and Coppola’s) Kurtz. On his way up the river, Conrad’s Marlowe describes the jungle in terms Herzog would relate to: “The great wall of vegetation, an exuberant and entangled mass of trunks, branches, leaves, boughs, festoons, motionless in the moonlight, was like a rioting invasion of soundless life, a rolling wave of plants, piled up, crested, ready to topple over the creek, to sweep every little man of us out of his little existence.” The jungle (s)mothers European man, his snowball heart and his desert God.

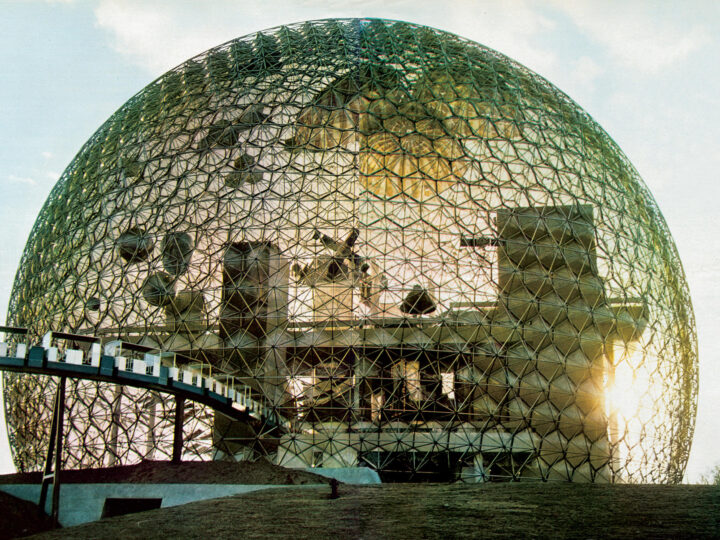

In this stifling mien, Euro-Americans test themselves by building Euro-American things: Fitzcarraldo‘s opera house, The Mission‘s palm-frond church, or Harrison Ford’s giant ice machine in The Mosquito Coast. Where do these anxious and heroic desires come from, this hubris audacious enough to drag a boat over a mountain? The text superimposed on Fitzcarraldo‘s opening aerials of the forest’s misty canopy provides a clue, stating that the Cayahuari Yacu Indians call the jungle “the country where God did not finish creation.” Conrad himself describes the jungle in Heart of Darkness as “featureless, as if still in the making,” and in Mosquito Coast, River Phoenix tells us that “My father said that God had left the world incomplete, and it was man’s job to understand how it worked, to tinker with it, and to finish it.” For the fathers, the jungle is where you perform the ultimate identification with the Father: to look upon the oceanic maternal chaos (Harrison Ford’s character calls it “earth’s belly-button”) and erect an image of your will.

In John Boorman’s Emerald Forest, the natives call Westerners “Termite People” because we eat the trees. But Technical People would be more accurate. Technology forms the West’s underlying subjectivity, which is why tools or guns aren’t ultimately as important in the jungle as those machines that mechanically reproduce our culture: record players, reel-to-reels, cameras, computers. Jungle movies are really quite insistent about this. Glopping on camouflage, Herr Arnold and his commandos blast “Long Tall Sally” on a boombox as they fly into Predator‘s Central American jungle. In FernGully, Zak’s Walkman pops up in the faerie village like the monolith in 2001 and later provides Zak the opportunity to impress the faerie Crysta when he hits the play button. As Fitzcarraldo’s boat enters Indian territory, he soothes the savage breast with a Caruso 78 on his gramophone. In Apocalypse Now, Robert Duvall hits the reel-to-reel on his chopper and blasts the gooks with Wagner. A few minutes earlier, Coppola himself appears in the film, a TV journalist screaming “Don’t look at the camera!” at Martin Sheen.

In the jungle, abstraction and mechanical reproduction anchor Western civilization. In Medicine Man, Sean Connery almost loses it when he’s unable to reproduce a cancer-curing plant’s chemical composition on his computers. For Fitzcarraldo, the gramophone is the very engine of his dreams. These machines justify us, cocoon us from the forest peoples and their spiritual and socio-economic realities. Contrast two scenes: in Emerald Forest, a photo-journalist is murdered by cannibals as they steal his pictures; in Burden of Dreams, Indians spend a large portion of their inflated daily wages on Polaroids of themselves. But perhaps cameras in the jungle are less about the natives than about us, about capturing our sense of ourselves. Filming their epics, skirting madness and disaster, Herzog and Coppola drew documenting cameras to their projects like flies to rotten mangoes. Perhaps we are all with Fitzcarraldo when he says “I am the spectacle in the forest.”

Long before boomboxes in choppers, or even before intrepid filmmakers proved their mettle in films like H.A. Snow’s Hunting Big Game in Africa With Gun and Camera (1922), jungle missionaries tested the power of the Book, civilization’s great reproducer of reality. The reason evangelist movies like The Mission and At Play are so often set in the jungle is that if the Lord’s Word can play here it can play anywhere. But the arrogant power of text underlies other jungle projects beside the theological. In At Play, Aidan Quinn is a missionary with a heart of gold who attempts to contact and convert the Niurana. Early on, he holds up a small black book and asks someone, “you know what this is?” We think it’s a Bible, but it’s a Niurana/English dictionary, and in that one gesture Quinn captures the paradox of his character and the idea of a “jungle book.” Scribbling notes, intoning scripture, both the scientist and the man of god are sworn to the written word. Where would the Brazilian ethnologist be without his journal, or the jungle missionary without his Good Book? Alone, without justification, facing the forest raw.

***

Of course, what the written word most seeks to capture and convert is not the jungle but its subjectivities: the painted, protean natives. If we are the spectacle, they are spectacular. More than the Western desert or Africa, the jungle holds the seriously Other, and most rainforest films highlight the electric moment of first contact between whites and natives with the same blend of terror and hope found in UFO accounts. After Tom Berenger parachutes out of a plane into an Indian village in At Play, they worship him as a god, and it’s Chariots of the Gods? revisited. When the Jivaro tribe climb onto Fitzcarraldo’s boat, they lightly brush their hands to his, a charged gesture equal parts E.T. and the Sistine Chapel. After being touched with a feather by Indians, the young boy in Emerald Forest tells his father about the “smiling people” in the forest and is not believed—and then is abducted. But perhaps the most brutally honest take on the Other in the jungle is found in Predator. After leading a commando crew into a guerrilla-filled Central American jungle, Arnold Schwarzenegger encounters a camouflaged deadly alien who blends seamlessly into the jungle (it even bleeds jungle green) and self-destructs before we learn anything at all of its purpose.

Historically, Westerners have found that the best way to deal with the ambiguity of the jungle alien is to kill it, enslave it, convert it, or study it. Distancing themselves from the decidedly mixed legacy of the Western, greed movies attempt to “ethnologize” the savages into peoples just as they “ecologize” the jungle into rainforest. This soft-core Dances With Wolves anthropology runs throughout The Emerald Forest, The Mission, At Play, Amazon, and Medicine Man, though more often than not the Amazonian tribes represented are in part constructed by Indian choreographers, language creators, and city-dwelling half-breeds (on the other hand, some of the tribes are legit, such as the Indians in The Mission who reportedly now speak English like Robert De Niro). But while truth value is invoked through documentary style—subtitles and drawn-out rituals—the ethnographic impulse generally fails to deliver either cultural depth or force of character. While The Emerald Forest shows many tribal rites of passage—puberty, courtship, death—Boorman also plays a glossy, stylized jungle game, most obscenely demonstrated in his evil cannibalistic Fierce People, whose African-styled makeup and dark skin color contrast with the paler hue of his attractive heroes, the Invisible People.

Because these movies are uncomfortable with Indian agency, even natives with lots of lines seem extras, their conversation heavy with mysticism and short on information or plain humanity. The very stupid film Medicine Man pisses on its own powerful underlying idea—that the forest and its people should be preserved as a pharmacopoeia of undiscovered medicine—by treating the tribal shaman like a fool. Supposedly, the man sees Sean Connery as a rival medicine man, flees when he gives a kid some Alka-Seltzer, and later refuses to direct Connery to the cancer-eradicating plant. What would you do if you were the shaman, an inheritor of the ancient wisdom of jungle healing? Would you tell a snotty white man with a Hollywood ponytail where the magic plant grows?

Speaking of magic plants, it should be mentioned that rainforest movies are perhaps the only mainstream movie sub-genre that does not demonize drugs. Psychedelic episodes pop up in these movies not only because the rainforest has copious amounts of hallucinogens, but because these plants represent the jungle’s power to transform even paleface lamebrains. It’s only after taking tripster snuff that the forest developer/patriarch in Emerald Forest responds to the Indians’ plight (in his vision he’s a jaguar who attacks a caterpillar). When the human logger Zak gets shrunk by the faerie’s magic spell in FernGully, he’s tripping, pure and simple, and emerges from the experience as an eco-warrior. Even if drug-free movies, everyone’s always flying around, choppers and tail-draggers and high-flying birds.

The greatest stoned moment fuses flight and self-transformation. In At Play, Tom Berenger is a long-haired cynical scrounge with Native American blood. Disgusted with himself for having almost bombed the Niaruna Indian tribe as a ticket out of the jungle, he guzzles a bottle of ayahuasca and takes off in his barnstormer. He soars through the gorgeous Amazon dawn, “at play in the fields of the lord,” before parachuting near the Niaruna. He enters the village naked, gets coated with paint and goes native, embodying the language and ritual that Aidan Quinn can only notate. Though Berenger’s Indian blood gives him a bit of an edge, the episode points out that when it comes to interfacing with the pagan other, psychedelics are at least as effective as dictionaries.

But the hardass finale of At Play suggests that both Quinn and Berenger are deluded. The missionary gets killed by a “converted” Indian as he attempts to warn the village of an attack, and Berenger decimates his tribe after catching a cold from Daryl Hannah’s lips. In the old days, in eco-disaster flicks like The Swarm, Naked Jungle, or even the more recent anachronistic Arachnophobia, South America was the source of horrific ecological mutations that invaded America, fueled by racist anxieties no more subtle than John Belushi’s killer bee. Now, we infect them, physically, culturally, just by the desire for contact. Even Herzog said that he divided his camp between Euros and natives because he didn’t want to “contaminate” the Indians.

What sets FernGully apart from this mythological flu is that with its faerie circles, spells, wise crones and Pans, the cartoon stokes the fires of the nature worship lingering in the kiddie-corners of Western culture. Realizing that the battle is for hearts as well as for minds, FernGully does not so much explain nature as re-enchant it. “There are worlds within worlds,” the old witch Magi Lune tells the heroine Crysta, and FernGully seduces us with them: dark and sparkling, wet and emerald green, hidden and high, we swoop through them. It doesn’t take a Deadhead to figure out what’s going on here, especially given all the mushrooms everywhere.

Even in FernGully‘s strong doses, this sort of pagan pixie dust is fairly routine in cartoons. But rather than just linger in never-never land, FernGully plugs those animistic desires into the ecological space of the rainforest. Like Ted Turner’s eco-cartoon Captain Planet, FernGully then maps the Manichean moral struggles implicit in the Disney tradition onto the ecology/industry divide. Nature—here or abroad—is magical and good; while the great machine of industry is not only demonically destructive but inhuman. After a magic seed of light enters his third eye, the dopey human Zak is born again as a rainbow warrior, armed not with data but with the unshakable soul of an activist. As politics it’s Luddite, but as spiritual eco-propaganda, it kicks like a kiddie Hearts and Minds.

Besides, FernGully gets a handful of points for being the first feature shown to the U.N. general assembly (and their families). The venue was significant, because the kind of global systems of relationships that must be imagined in order for ecological thinking to take hold are vaguely implied in the United Nations. Far more is implied in June’s U.N.-sponsored eco-summit in Rio, as Brazil and its rainforest economies are already something of an allegory for environmentalism in an age that demarcates the painful absurdity of the nation-state as well as the underlying poverty that drives so much degradation. Bowing to green pressures both internal and international, Brazil and Venezuela together set 68,000 square miles of rainforest aside as reserves for the roughly 20,000 Yanomami Indians. Unfortunately, thousands of garimpeiros, generally poor Brazilian gold miners, were displaced by the enclosure and began foraging into Venezuela, cutting down trees, infecting Yanomami, and poisoning the soil with mercury. Venezuela responded by seriously militarizing its border, rounding up miners, bombing airstrips (including one named after the Hitler of eco-terrorists, Saddam Hussein), and even shooting down a plane. The Brazilians are also beefing up their military muscle. It’s as if Europe’s first mad dream of the rainforest—the search for El Dorado, so insanely represented by Herzog in Aguirre, the Wrath of God—is clinging to the land like bad karma.

So here we are, deep in the speckled shadows of the rainforest, a space that embodies Gaian ecology as well as the cultural, political, and economic ecologies that twist through nation-states like so many anacondas. We are cloaked beneath a canopy of consumer culture, which tells us we will always be safe, and that the forest goes on forever. But there are whispers of endings. They say you can climb a tree to see for yourself, but the perspective has a price. We remember that when the Cheech and Chong bus peeped through the leaves in FernGully, it’s like Chef getting off the boat in Apocalypse Now. When Sean Connery in Medicine Man and Crysta in FernGully break through the canopy, their exhilaration is our own dream of finally getting the “big picture” and it darkens just as quickly. There is black smoke on the horizon, and it’s coming this way. As the shaman in The Emerald Forest puts it, the edge of the world is getting closer.

Originally appeared in The Village Voice