The Sacred Wisdom of Bugs the Elder

To grapple with Ted Turner’s 24-hour cartoon network, you must address childhood, not because the classic cartoons on the channel are childish, but because beings a child is so cartoon. When you’re a kid, you’re tripping all the time. Objects warp, animals rule, and funny noises abound, while the speckled beasts of dream are always lurking under beds and popping out of closets. Though most of the classic animation kids imbibe from TV (Warner Bros., MGM) was initially developed for adults, toons—like sugar or spinning around wildly—have a more powerful effect on soft, prepubescent brain cells. Far from turning kids into vegetables, the phantom tollbooth of television is actually an ally, assuring them that the world really is as they perceive it: intensely animated.

And intensely violent. While the exact effect of cartoon violence is no easier to suss out than the Indo-European derivation of “Yabba-Dabba-Doo,” these fluid and kinetic ballets tell crucial tales about the endless war between desire and the world. With mayhem at once endlessly creative and repetitive as hell, Tom & Jerry lay down the golden rule of karma a lot better than the Bible, just as the Tasmanian Devil, Daffy Duck, and any number of Tex Avery’s trademark bulging eyeballs provide telling lessons about the id’s limitless font of hunger, fear, and shameless behavior. And Wile E. Coyote—Wile E. is the Ahab in all of us, his universe becoming more vengeful and bizarre in exact proportion to the extremity of his urges.

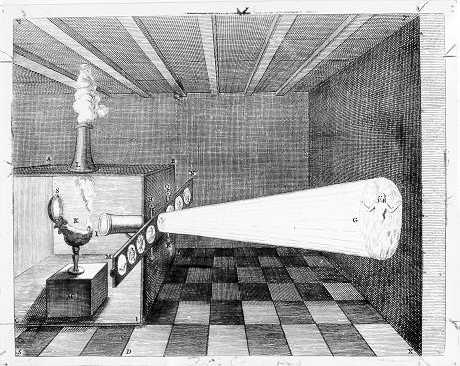

Nonetheless, projecting their own literalism onto the metaphoric jungle of the animated young mind, droves of parents have worried and complained about toon violence. The result is Saturday-morning shows not only lacking in bone-crushing fisticuffs and the brute-force physics of head-on collisions, but the transgressive power such events embody. What the Ralph Naders of the imagination don’t recognize and the kids intuitively do is that a pummeled Popeye or a lacerated Daffy are just vehicles for cartoons’ true objects of loving satire: time and space, mass and energy. In the hands of wizards like Tex Avery and Chuck Jones, the laws of physics are both powerfully real (a frying pan is less pliable than your face) and an incomplete description of the universe (you can stand on air, but only if you don’t realize you’re doing it).

Matter is always magical in cartoons. When Christians complain about the paganism in action-adventure shows—JC being the only true Master of the Universe—they’re not totally off the wall. Like comic books, these shows are defiantly pantheistic—be it Birdman, who draws his power from the Egyptian sun-god Ra, or Aquaman, lord of the seas. As an evil green ice creature says in an episode of Space Ghost recently aired on the Cartoon Network, “whoever controls the elements controls the universe.” Few ceremonial magicians would disagree.

But while the connections between cartoons and the magic of fairyland are pretty obvious, folks forget about the other traditions toons keep alive. Cartoons may be, as Foghorn Leghorn would say, “as subtle as a hand grenade in a barrel of oatmeal,” but they’re about as close to formal art appreciation as most of us get. Watching the backgrounds of Merrie Melodies mutate over the years, and tracking those increasingly stylized lines as they migrated through Mr. Magoo and The Jetsons into the abstract backgrounds of The Pink Panther, I absorbed the development of modernism by having it etched into my retinas. Parents may not have noticed, but Bugs and friends were a veritable young person’s guide to the arts: Elmer Fudd’s asides to the camera taught me how to recognize the met-boundaries of media, while puzzling images of bobby-soxers screaming “Frankie!!” in front of this swarthy wraith introduced me to cultural history. And where did we first encounter the grandeur of Wagner or the playfulness of Mozart? As Elaine said to Jerry recently on Seinfeld, “All your knowledge of high culture comes from Bugs Bunny cartoons.”

More than anything else on TV, classic animation carries the torch of physical comedy passed on by vaudeville and the silents, and it’s from these working-class and immigrant roots that cartoons draw much of their earthiness and anti-authoritarianism (I’m not talking about Disney here because Disney isn’t funny). Political truths abound: Bread lines and the urban down-and-out populate Max Fleischer’s early Popeyes; Yosemite Sam told crusty truths about the American white male that Bonanza would never dare reveal; and Yogi Bear gave me a praxis of mooching and sloth long before I read Bob Black’s underground tract The Abolition of Work. And cross-dressing Bugs produced enough anarchist pranks to fill volumes of Re/Search—and he did it all without getting pierced.

***

Growing up as a dial-flipper, there comes a day when you finally stop and actually watch one of those long and boring movies where adults talk and argue and kiss. You expect coconuts to fall on their heads, but it doesn’t happen. Then you realize you’re watching your future destiny, and from that moment on, cartoons become the only channel back. Even if your tastes change to anime, Bakshi, and the various tournées, you can never grow tired of the classics. That’s why about 40 per cent of cable cartoon watchers are grown-ups. If it weren’t for them (us?), Ted Turner would never have launched his network.

For all their weaknesses, narrowcasting ventures such as MTV, CNN, and the Weather Channel address the essential facets of the human condition: comedy, tragedy, song, trade, news of the realm, nature divination. The Cartoon Network and the recently launched Sci-Fi Channel argue for drugs and prophecy, for an expansion of cable consciousness.

Not that the Cartoon Network rules. Ted Turner’s cartoon holdings are the greatest in the world—Warner Bros., MGM, Paramount, and the vast vaults of Hanna-Barbera, who essentially ruled the world of made-for-TV toons. But much of this stuff is already in circulation, and the Network has a long way to go before it can claim to by animation’s hall of fame. Though even an hour of Adam Ant is better than the stuck-in-the-’80s New York art-school drool that for the most part clouds MTV’s Liquid Television, that doesn’t make up for the lack of The Bullwinkle Show, Speed Racer, Fat Albert, Astro Boy, Heckle and Jeckle, Dick Tracy, Superman, Mighty Mouse, Felix the Cat, The Pink Panther, or Mr. Magoo. And though the Network is showing some original Popeyes from the ’30s and ’40s, it doesn’t do enough genuflecting before Popeye animator Max Fleischer. As a recent A&E special demonstrated, Fleischer was without a doubt America’s most underrated popular animation genius. He beat out Disney on sound, he was gritty and insanely surreal, and to my eye he was the true father of R. Crumb—and hence, to much of the ’60s underground. But the Network doesn’t give spinach-man his own block, they’ve yet to show any of Fleischer’s even more brilliant Betty Boops, and, most unforgivably, they colorize the toons.

For all its classic movie studio animation, the Cartoon Network will be made or broken on the power of its Hanna-Barbera holdings. William Hanna and Joseph Barbera gained fame as the Sam Peckinpahs of MGM, turning out righteously violent Tom & Jerrys and winning lots of Oscars. But seeing the tube looming on the horizon, H-B started their own studio and began cranking out cheap material for TV in 1957. Gearing their tunes to kids rather than adults, they helped establish a market they would lord over into the ’80s. Emphasizing clean lines, straight-ahead angles, and cookie-cutter figures, they perfected low-budget techniques of limited animation (the reason so many H-B characters wear neckties is that it disguises the fact that only their heads are being animated). True, one of the greatest cartoons of all time, The Bullwinkle Show, was animated like shit, and H-B did create many funny characters; but for classic animation fans like Leonard Maltin, H-B might as well be Satan. And no wonder: If you watch Looney Tunes for an afternoon and then go outside, the world starts to pulsate and glow. But after a few hours of Quickdraw McGraw or Pebbles and Bamm Bamm, the world goes 2-D.

Which is why the real treasures the Network has unearthed from the H-B vaults may be the bristling action-adventure shows that reigned briefly in the mid-’60s. Clearly feeding off the voluptuous lines and mutant exaggerations of Marvel Comics, these toons ruled until parental complaints thinned down their ranks (and their blows) dramatically. Johnny Quest is a bit too Boy’s Life for me, but Mightor, The Herculoids, Birdman, and the fabulous Space Ghost (who possesses the most masterful patriarchal vocal chords of all time) are all treasures, with loopy creatures, rupturing volcanoes, weird trees, ’60s soundtracks, and, best of all, excellent violence.

This is not to deny the archetypal punch of Shaggy and Scooby, Huckleberry Hound, or the patently mad Hong Kong Phooey. And The Flintstones, the greatest crossover toon/sitcom before The Simpsons, deserve their page right out of history. But any attempt to lionize Hanna-Barbera comic characters beyond the undeniable pleasures of nostalgia, camp, and some good jokes is doomed to fail, because the spoofs are too puffy, the action too bland. As a bleak commentary on a world glutted with hard-sell jingles and novel appliances, The Jetsons is fine, but I’d rather watch a reel of Jay Ward Cap’n Crunch ads and take visual pleasure in the contradictions of toon shills.

The great TV animation of today goes beyond Hanna-Barbera’s low-tech cutouts. Ren & Stimpy, The Simpsons, Batman, Beetlejuice, Rugrats, MTV promos, and Liquid TV‘s “Aeon Flux” are all elastic or hyperstylized enough to function as drugs. Good toons warp the eye. They melt the hard edges of external reality into the gooier, ghostlike forms of the mind, a necessarily ironic dialectic excellently staged by a Yogi Bear episode I caught recently. Yogi, Boo Boo, and Ranger Smith stumble onto a secret military rocket launch in Jellystone (Hanna-Barbera love missiles). Of course, someone accidentally pulls a lever and the trio take off. “We’re in outer space!” Ranger Smith cries out as the warped logic of cartoons smashes his asphalt reality to rubble. “Well, sir,” a wise and bemused Yogi replies, “how doe we get back to inner space?”

Originally appeared in The Village Voice