West Coast Festival Culture

The following is adapted from the introduction to Tribal Revival, a new collection of photographs by Kyer Wiltshire, who has been shooting the neotribal festival culture of the West Coast for many years. I contributed texts throughout the richly designed book, which covers everything from garb to hooping to “prayerformances.”

In the summer of 2006, I had the good fortune to attend a large and boisterous gathering of spirit mediums in the benighted land of Burma. These mediums, who channel dead heroes and courtesans known as the nats, play a vital role in Burmese life, and for centuries they and their followers have been gathering annually at a village called Taungbyon, which lies just outside the now grimy and hectic city of Mandalay.

My companion and I left our hotel early to beat the crowds. Despite the early hour, over-stuffed taxis and trucks piled high with revelers already lined the route, their touts crying “Taungbyon! Taungbyon!” to attract more passengers. The road became thick with vehicles, begging cripples, bicyclists, families on foot. Almost everyone radiated an air of expectant, electric glee. We were still miles away from the town itself and what would turn out to be one of the most madcap celebrations of music, dance, rum, and the gods I have ever experienced. Nonetheless, an almost animal instinct fluttered up and down my spine, a wordless buzz that I recognized from a youth spent at Grateful Dead shows. It felt like the onset of a crush, or of a potent concoction. Something strange and special was at hand: festival.

This is the first thing you learn about the festival: to get there, you must leave here. You must, in other words, cross over, out of the ordinary world. Maybe you haul your tent to a glade in the middle of nowhere, and maybe you just hand some guy your ticket. But either way, you must cross a threshold. Without even noticing it, your normal body armor starts to slip away, as you instinctively recognize that the strangers around you are not quite so strange anymore, for even if they look strange, which could easily be the case, they are no longer judging you in the same way that people in the mundane world do. They are more likely to be friends you just haven’t met yet, fellow conspirators of joy.

The anthropologist Victor Turner famously used the word liminal to describe the passageway between the known and the unknown, the path that takes you to a nomadic territory that lies in-betwixt and in-between. Turner was interested in traditional rites of passage, those tribal ceremonies that guide participants through the process of social transformation—from childhood to adulthood, say, or from novice to shaman. Such rites are important inspirations for today’s neotribalists as well, both consciously and not. For though the festival rarely marks its participants with the obvious cuts and tattoos of a puberty rite, it does hold out the potential for real change, and this potential lies in the liminal: the deeply felt sense that the normal rules are suspended or warped, that a possible world is emerging, and that a new self can rise to greet it.

Every summer, tens of thousands of participants descend upon dozens of festivals and gatherings, great and small, that occur on the West Coast of North America: Shambhala, Oracle, Moontribe, Lightning in a Bottle. The names of these clans and crews are legion: hippies, ravers, pagans, crusties, free spirits, burners, seekers, travelers, eco-warriors. They gather together to dance, to escape, to hold ritual, and to craft a visionary culture based on community, creative self-expression, and a celebratory earth wisdom. Labels are always dangerous, but an honest name for the scene is neotribal. These are the new tribes, recreating and reinventing patterns of organic culture that are inspired by the premodern past but designed for a high-tech planet hurtling through a period of unprecedented global change.

Tribal Revival is both an introduction to the neotribal scene and an expression of its creative spirit. For six years running, Santa Cruz photographer Kyer Wiltshire has been devoting his summers to the West Coast festival circuit, traveling from classic countercultural gatherings like the Oregon Country Faire to more madcap and new-fangled ones like Burning Man, from colorful fantasy pageants like Faerieworlds to cutting-edge outdoor raves like Symbiosis. For a photographer, these gatherings are an embarrassment of riches. In festival culture, everyone is part of the picture—physical arts like poi and hooping are widely practiced, crafters make and sell art and ritual craft, and people treat fashion as an invocation and a performance. Everyone, in fact, is performing—not posing so much as actively participating in a collective game whose goal is beauty, wonder and transport.

Festivals can be a wild time, but for many participants, the festival is also a vital space of cultural invention. Within the environs of the gathering, half sacred and half imagined, another possible world appears. Despite the variety of festivals and clans, certain values come to the fore: community over consumerism, the power of the feminine, the wisdom of consciousness exploration, and the ethical call to develop a hands-on harmony with the earth. Some of these values grow out of countercultural movements generations old, and others are modeled on the folkways of other times and places—sometimes with respect, and sometimes with a hasty hunger. Like all ideals, neotribal values are rarely realized in full, and are more complex and contradictory than they initially appear. That said, the West Coast’s tribal fusion must be seen as a conscious and deeply creative bid to craft an intentional culture through the vehicles of shared imagination, group work, and the collective joy of the dance. It is an explicit attempt to recover an ancient and even shamanic pulse in the midst of a technological civilization shuddering at the limits of its capacity.

People have gathered in ritual celebrations throughout recorded history, and no doubt back through the depths of prehistory as well. At the same time, and despite the tremendous differences in human cultures, anthropologists recognize a shared language of the festival. People wear special attire, sometimes donning masks or fancy headgear, and sometimes painting their bodies. They drink and eat and dance, often with great exuberance and for hours or even days on end. Intoxicants are taken, if they have them, and maybe the spirits show up and join in the dance. Emile Durkheim, who believed that religion was fundamentally a social process, called the energy raised by such gatherings “collective effervescence.” And though this powerful group buzz is invariably dedicated to the gods of earth and sky, it often generates its energies through the more secular strategies of a party. These entwined goals are key to the modern neotribal festival culture, whose exuberance bubbles up in the space between sacred and profane, ritual and fete, ceremony and celebration.

The festival creates a liberated reality that’s always in flux, a community of play with its own rules and codes, but also with a willingness to suspend rules and codes. When the festival is really working, people are able to slip outside of established social roles and habits of behavior, and to act from deeper and more singular desires—in other words, to grow more autonomous. The festival has its own forms of conformity of course, its own cliques and fashion fascism. Autonomy always dances with the ways we construct and belong in community, until those communities themselves become more open and free.

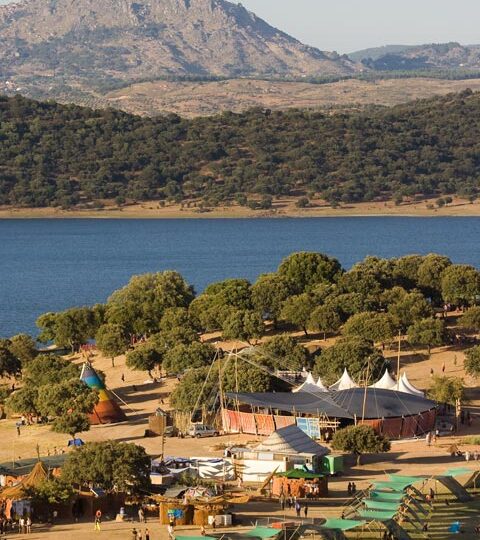

What’s most important for the festival is that the liminal quality of being in-betwixt and in-between becomes, for a spell, just the way things are. This can only happen when you marry a special kind of place with a special kind of time. The place is a village, roughly, or a nomad camp, lying on the edge of wilderness, even if the wilderness is just a line of trees or a parking lot. The layout of the festival grounds becomes a map of a possible world, with places for food, for trade, for workshops, tarot readings, art galleries. These places are colorful, fanciful, and surprising. They invite interaction and imagination. Names and points of reference evolve—not like the crisp grids of Google Maps, but more like the imaginary kingdoms that kids discover, and make, in their backyards or local parks.

Even more important than the unique space of the festival is its unique sense of time. Historically, most large festivals were linked to specific times of the year—the celestial dance of sun and moon, the rhythms of agriculture, the annual celebration of saints’ days or miracles. Today’s West Coast festivals are largely decoupled from traditional holidays or growing seasons (with the exception of a certain fall harvest). But by happening annually, which most of them do, festivals still create a deep sense of repetition and return. And when these different festivals are laid end to end from spring to fall, they string together a season, allowing the truly devoted (or the cleverly entrepreneurial) to travel the circuit continuously like the nomads of old.

There is another kind of time at the festival, one that takes us far beyond the prison of the calendar. This is the internal and sometimes magical sense of time experienced by participants. Instead of the objective regularity of the clock, with its repetitive grind of getting and spending, the festival stirs up a round, spontaneous, and luxuriant kind of time, sometimes restless but deeply free. The night especially can seem “timeless,” which does not mean that it is static, but only that it does not strive. The flow of encounters, of music and dance and conversation and food and drink, is sufficient unto itself, and so feels perfectly full.

Beneath this easy flow of time lies an even more profound pulse, one that I suspect most deep festival goers have experienced but that can still come on with a bit of a shock. I first tasted it in 1991, at the annual national Rainbow Gathering, which that year took place in Green Mountain National Forest. Following the silent peace meditation that traditionally takes up the morning of the 4th of July, an immense iridescent halo surrounded the sun in the blue skies above, and the crowd, and me, erupted with roaring hippie glee. Two stilt-walkers were blowing wild melodies on their horns, the drums clattered with unusual coherence, and someone lifted some peculiar idol aloft above the crowd. At that moment I knew, with almost unbearable conviction, that this exact moment had occurred before, that it echoed back through a thousand years of a thousand dusty stomps, and that all festivals were really just one festival, eternally recurring.

This feeling itself, I would come to learn, is an ancient one, and in it lies the seed of renewal. In his book The Eternal Return, the historian of religion Mircea Eliade described how certain rituals allow mythic time to erupt inside mundane history. In particular, Eliade talked about annual tribal ceremonies that stage the recreation of the cosmos. The idea, which is found throughout primal societies, is that by ritually returning to the chaos at the beginning of things, and then reenacting the emergence of our ordered world, the cosmos itself is renewed. Such ceremonies give us an insight into the deep impulses of the festival culture, within whose electronic noise and psychedelic chaos stir new forms of living and being together on this planet. The cutting edge festivals today are green and sustainable, with workshops on alternative fuel and carbon footprints rounding out the music and dance. Even more vitally, the infrastructure of the festival itself is becoming an experiment in right planetary living. This isn’t just global warming window dressing. This represents an intuition, welling up from primal memory perhaps, that the festival culture is a foundation of world renewal.

As a culture of the earth, the neotribal scene also sink its physical roots into the environment it happens to call home. The festival culture depicted in Tribal Revival draws much of its strength and inspiration from sublime power, variety, and beauty of the West Coast, which is why so many festivals plant themselves as far away from strip malls and parking lots as they can get. At the same time, neotribal culture reflects the realities of today’s globalized world, and is by no means limited to the West Coast. Neotribal festivals take place across the planet, creating a borderless network of cultural collaboration that has been spread and amplified by the same forces that are shrinking the globe for everyone else: mass communications, open markets, air travel, the online glut of sounds and sights and information. Today there are intense and vibrant neotribal scenes in Portugal, Brazil, Japan, India, Australia.

That said, there is something special about the West Coast and its particular fusion of fabricated traditions, spiritual hedonism, earth mysteries, deep beats, and edge culture. That uniqueness lies partly in the land, but it also lies in the unusually deep history of West Coast counterculture—a new-fangled North American tradition of heathen hedonism whose ineffable combination of exotic drama, earthy communion, and feral joy reaches back generations.

Adapted from the Introduction to Tribal Revival: West Coast Festival Culture