Dollhouse by Josh Whedon

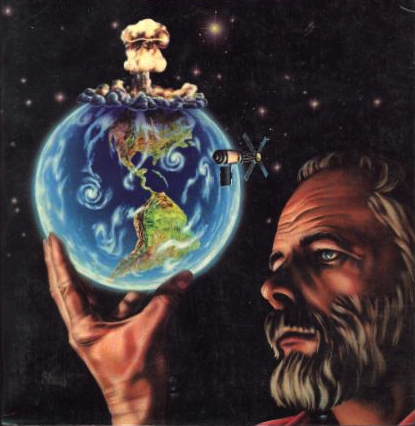

At its best, science-fiction TV satisfies our desire for escapist pop while also holding up a mirror to the zeitgeist, and especially to those deep fears and desires that elude the strategies of more conventional and realistic narratives. Battlestar Galactica, with its dark meditations on prophecy, war, and Cylon identity, is the shining recent example, but seemingly cornier fare can also provide candy-coated conundrums that bear rumination, and that almost sneak up on you with their significance. Dollhouse, a Fox TV show created by Josh Whedon—the cult-show-breeding mastermind behind Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, and the too-briefly-seen Serenity—is a glossy, jiggly, fisticuffs entertainment marked by many of the Whedon moves that made Buffy such a success: playful banter, accessible smarts, and a pleasing air of unreality. At the same time, Dollhouse manages to sink its sexy teeth into some of the core anxieties—and possibilities—of our neurological century.

The show, whose first season has just been released on DVD and which has been renewed for a second season despite mediocre ratings, centers on an illegal and quasi-mythical organization in Los Angeles that uses a fantastic neurological technology to provide programmable human “dolls” to wealthy clients for any number of tasks: sex, companionship, criminal deeds. Between assignments, the dolls—whose original selves have contractually agreed to offload their personalities and serve five-year terms of servitude before getting their selves back—live like contented lobotomy patients in the “dollhouse,” an underground facility that resembles an Ayurvedic spa, Santa Monica-style. A rogue cop is hunting the organization, which is also experiencing its own technical difficulties—most notably the pesky tendency of some dolls to grow towards self-awareness, and occasionally explode with festivals of bat-shit mayhem.

On one level, Dollhouse is just the sort of goofy, cleavage-baring thriller you might expect to see on Fox on a Friday night. Hotties and motorcycles abound, edits are slick and fast, and the requisite chase scenes and bone-crunching ninja brawls are often executed in high heels, for which the show has a considerable fetish. Despite the intelligence and wit of many episodes, the narrative flow often feels more like a roller-coasters than an organic story, with abrupt and needless twists and turns that derive less from plot or character needs than the compulsion to yank the audience around. The acting is so-so throughout, with few of the actors rising to the challenge of embodying characters who are not really “characters” at all, but flesh-bots who oscillate between innocuous zombiedom and a revolving door of one-shot personalities.

Despite the show’s glaze of artificial popcorn butter—or perhaps, given the loop-d-loop logic of sensationalist popular culture, precisely because of its disarming layer of cheese—Dollhouse takes a reasonably meaty bite out of one of the more ominous and potentially liberating conundrums of 21st century life: the thoroughly constructed nature of human identity. The show frames this conundrum in terms of neuroscience and the pervasive pop metaphor of the mind as a programmable input-output device. Original personalities are “wiped” and stored on cartridges that resemble old 8-track tapes; other “imprints” are not only shuffled between the dolls but remixed into the perfect blend of characteristics for any given job. The show’s ambivalence about such “posthuman” technologies is captured by the character who does all the wiping and remixing: a smug, immature, and charmingly nerdish wetware genius named Topher Brink, whose simultaneously dopey and snarky incarnation by the actor Fran Kranz reflects the weird mix of arrogance and creative exuberance that inform so much manipulative neuroscience.

For a science-fiction thriller, there is not much emphasis on gadgetry. In one episode, the doll Echo, played by Buffy vet Eliza Dushku, is implanted with a “brain camera” that turns her into a remote surveillance device that allows the ATF to spy on the creepy religious cult she has been programmed to infiltrate (paradoxically—or perhaps allegorically—the device temporarily blinds her). But overall, Dollhouse is much less concerned about posthuman technology than it is about current social reality, or at least about how the late capitalist media culture that saturates our lives will transform through posthuman technology into a dizzying scramble of identity and desire.

That’s why Dollhouse can be read most basically as an ironic reflection of Hollywood itself, and especially the peculiar fate of actors living in LA. When not on assignment, the dolls, who are uniformly fit and attractive, spend their time doing yoga, swimming, sleeping, and eating 5 star food—presumably with vegan and raw options. “It’s important to exercise,” they murmur like Stepford wives. “I try to be my best.” This almost literally mindless maintenance of happy leisure—the ideal of SoCal’s hedonic “good life”—is then contrasted with the caricatured and often highly skilled roles these hard-body blank slates are episodically compelled to perform. The dollhouse can be seen as a Hollywood house of mirrors. In one show, we even glimpse the operation’s enormous costume room, a museum of fabricated identities that would be far more familiar to the actors on the show than to the vast majority of the punters watching the thing on TV.

On a deeper level, the business of the dollhouse—which one staff member sardonically describes as being “pimps and killers, but in a philanthropic way”—simply literalizes aspects of human power relationships that all of us are already familiar with in the mundane, not-quite-SciFi world that we already live in, and that the show itself often self-consciously references. Lovers use one another to sustain fantasies of dominance and submission, cult leaders enslave believers, military organizations treat soldiers as pawns, and even the most successful pop music diva is, as one character proclaims, “a factory girl.” All of us are dolls sometimes, and dollhouse engineers other times. Cleverly, Dollhouse incarnates this fundamental split between masters and slaves in the panopticon-inspired architecture of the dollhouse set itself, which places the employees who run the show on a balcony that looks down onto the dolls flexing their muscles or sleeping below. The space has an open, airy feel, with few locked doors, and this deceptive informality disguises an invisible architecture of control.

The uncanniness of invisible controls systems—whether in fictions of real life—helps motivate the paranoia that runs through the show. This stretches from the “gigantic multipronged conspiracy” of the international dollhouse organization itself—captured in one episode in the classic image of a wall covered with an octopus of documents, thumbtacks, and linking strings—to the fact that, in a BSG-like twist, we don’t always know which new characters we meet are actually dolls on assignment. Occasionally, these paradoxes take us into pure Philip K. Dick territory, particularly towards the end of the first season, when—spoiler alert—the cop pursuing the organization not only discovers that his lover is a doll, but watches her concocted personality get momentarily over-ridden by a more mysterious persona whose covert messages seemingly come from an unknown moll inside the organization.

Shadowy international conspiracies are the bread-and-butter of thrillers these days, but the undertow of suspicion that runs through Dollhouse ultimately turns on a premise that hits pretty close to home: the possibility that you yourself, dear TV fan, is more of a construct than you suppose. In one episode, a number of random people on the street are asked for their opinions about the dollhouse, which many discount as an urban legend. One complains that the organization, if it exists, takes away “everything that makes you more than a cluster of neurons.” But isn’t this the big question: what if we are just a cluster of neurons? And what does that possibility do to our understanding of morality and choice, fantasy and personality?

While Dollhouse mostly hints at the darker dimension of the neuron cluster, it also hints at some of the upside—not least of which is the functional immortality that might come with replicating that pattern of neurons, a revolutionary possibility that the show flirts with but, lamely, only barely explores. Many of the missions the dolls undertake also heal far more than they harm, and there are hints as well that the organization itself is not as nefarious as it first appears. Even the dolls are not totally mindless slaves—as the season progresses, a few begin to exhibit behaviors that go beyond their programs, some of which reflect deeply hard-wired traces of their original personalities and more interesting ones that suggest budding forms of self-consciousness and moral agency.

In one episode, the doll Echo is hired out as an art thief, and an encounter with a Picasso painting whose cubist portraiture she interprets as signs of a broken self. But Picasso’s fractured perspectives could equally be seen as an attempt to expand beyond the conventional self and its “single vision” into a wider embrace and affirmation of the many identities that potentially flow through us—a flow that may soon become more of a tsunami.