A Visionary Field Guide

Mushrooms are all about appearances. They emerge in the dark of night or the blink of an eye, and sometimes disappear just as quickly. Now you see them, now you don’t. No wonder the ancients thought they were germinated by thunderbolts: they don’t seem to grow out of the ground so much as to pop out of thin air. And now we know that the mushrooms that do show up above the surface are themselves just transient representatives of a more lasting organism: the branching tangle of multi-cellular fungal threads that lies hidden beneath the soil. Under certain conditions of temperature and moisture, this internet of mycelium—sometimes vast, sometimes ancient—sends up fruiting bodies like periscopes in order to distribute reproductive spores. The mushroom, then, is already an icon of itself, appearing in our visible world of fields and forests like an avatar of some deeper, subtler spirit.

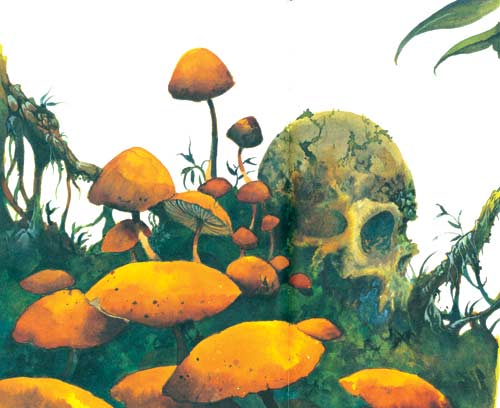

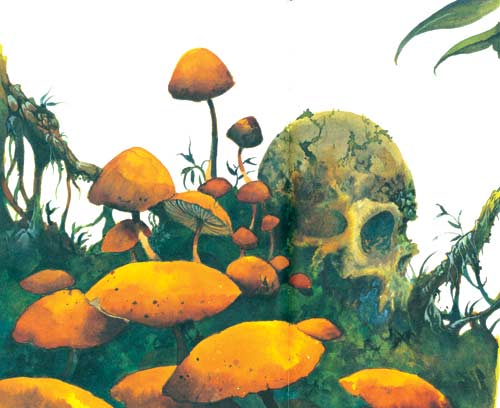

The appearance of the mushroom bodies themselves also resemble nothing else on earth, even though these shapes so often remind us of other things: hats and gnomes, umbrellas and cocks, or furniture for toads. Goofy and exotic, elfin and obscene, mushrooms are caricatures of themselves. Their colors can be vivid and strange: blue-blacks and purples and rusty sunset blazes that seem more like the work of fin-de-siècle bohemian artistes than the cheery sign painters who give birds and flowers their bright and happy hues. Some mushrooms even glow in the dark.

Growing out of rot or turd, in damp caves or along dead tree stumps, mushrooms appear in worlds that lie between life and death, animal and plant. Is it any wonder that our ancestors, making their way through the enchanted landscapes of life before science, associated mushrooms with the uncanny, with mischief and sorcery, with spirit transport and immortality? This occult legacy is still inscribed in the common names of so many species: Magecap, Witches Hat, Destroying Angel, Devil’s Urn, Jack-O-Lantern. Or consider the dozens of mushroom species whose fruiting bodies form circles or arcs on meadows and the forest floor. Can you fault the old ones for calling these designs “fairy rings”—ronds de sorciers in French, hexenringe in German—or for claiming that they mark the circle dances of pixies or hags? Even the Japanese call the fly agaric beni-tengu-take (“scarlet tengu mushroom”), after the tengu—Japan’s mythical bird-like trickster imps—who are said to get drunk from eating them.

Mushrooms are all about appearances, and appearances deceive. Even as the ancient Taoist sages wandered through their misty pine mountains hunting for the Marvelous Fungus that grants eternal life, many other mushrooms can—and do—kill. In English we find a traditional linguistic divide between mushrooms (edible) and toadstools (deadly), but this distinction, like most black-and-white moral schemes, does not hold. The mushroom is fundamentally undecidable. Experts still confuse tasty and poisonous specimens, while fungal classification itself remains a notoriously hairy and fractious scientific problem. “The more you know them, the less sure you feel about identifying them,” said the composer John Cage, an ardent mycophile. “Its useless to pretend to know mushrooms. They escape your erudition.” Embodying both elixir and toxin, salve and bane, the mushroom may be biology’s purest example of what Plato called a pharmakon—a term, or a substance, that can mean both poison and medicine.

Somewhere between immortality and death, poison and medicine, lies the realm of visions. Given the mushroom kingdom’s enchanted profile in folklore, is it any wonder that within its alkaloidal pharmacy there exist a handful of molecules that shift and magnify the human mind? Over a hundred species of mushroom are known or suspected to contain psilocybin and/or its near relatives psilocin, baeocystin, and nor-baeocystin—the main psychoactive ingredients in the “shrooms” that are now found and gobbled across the planet. A smaller set of Amanitas—the most famous being the red-coated, pearl-spotted A. muscaria, the most caricatured of all mushrooms—contain muscimol and ibotenic acid, which are also powerful if more tricksy hallucinogens. Other, weirder species lurk in the wings, half-grokked blends of toxin and drug.

Mushrooms are all about appearances, and the visions that come with a few dried grams of shrooms are nothing if not a stream of appearances. At low doses, the visible world of rocks and clouds takes on a mirthful incandescence that blooms, on the inner screen of the eyelids, into mandalas, mosaic patterns, and other abstract convolutions. At higher doses the mushroom seems to act like a portal into other dimensions. As waves of powerful emotions—awe, bliss, terror, hilarity—bathe the mammal body, the bemushroomed person become what mycologist R. Gordon Wasson, echoing Emerson, famously called a “disembodied eye.” Cyclopean palaces and blinking UFOs may rise out of lost junglescapes, while insect lords and almond-eyed goddesses play hide-and-seek behind shimmering veils of alien hieroglyphs. One’s mind becomes the stage for an apocalyptic mystery play, whose final, flirting curtain promises a revelation of such cosmic import that it threatens to unravel the very texture of time and self.

Given such jaw-dropping phantasmagoria, it is understandable that some students of the mushroom believe that in the fungus they have stumbled across the hidden origins of human religion. Perhaps the most celebrated of these was Wasson himself, a Wall Street banker who, in a 1957 edition of Life magazine, revealed the existence of a “magic mushroom” cult practiced by peasant healers in the remote mountains of Oaxaca. Given the great deal of evidence we have for pre-Columbian use of Psilocybe mushrooms in Mesoamerica, Wasson reasonably believed that he had discovered the smoldering embers of an ancient tradition. Wasson went on to argue that psychedelic fungi contributed the secret sauce for soma, the mystical brew lovingly described in the Vedas of India, as well as for the kykeon guzzled during the ancient mystery rites of Eleusis.

Wasson was hardly alone. In 1970, John Allegro published The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, which argued that the origins of Christianity were fungal as well, a secret encoded in the Eucharist. Druids and Vikings were also speculated by some to be magic mushroom eaters, an argument that went down well in a counter-culture striving to ground its own hallucinogenic explorations in deep history. In the early 1990s, the scintillating psychedelic bard Terence McKenna picked up the thread and wove an even larger tale. As the rave scene sparked a new wave of mushroom gobbling around the globe, McKenna argued that the mushroom’s semiotic rocket-ride kick-started language itself, and that human consciousness can be traced to the first ancestor who decided to munch some of the cow-pie companions that popped up on the Serengeti plains. In other words, mankind is mushroomkind.

But appearances can deceive. Despite the fact that Psilocybe spores carpet-bombed wide swaths of our planet millennia ago, there is little hard evidence for psychedelic mushroom use in traditional societies—even among groups that consume other mind-expanding plants and brews. Along with Mesoamerica, where royal weddings were capped with mushroom-fueled dance parties, the only other bulls-eye is Siberia, where shamans (and ordinary folks) consumed Amanita muscaria, the non-psilocybin-containing fungus whose psychoactive alkaloids were also passed around through the quaffing of urine. In Europe, there is scant suggestion of mushroom use, despite the ubiquity of several species. Solidly documented cases of probable Psilocybe intoxication begin in the eighteenth century, and they suggest that these accidental shroomers discovered nothing particularly cosmic in their trips—although some did get the giggles.

Nonetheless, a number of authors insist that a hidden mushroom cult of fungal gnosis, rooted in Neolithic shamanism, has been passed down secretly. Given our theme here, what’s most interesting about the evidence they marshal is how much of it depends on the appearance of mushroom-like images. As far as the Neolithic past goes, McKenna was particularly fond of a rock-art image from Tassili, Algeria, which depicts a wizardly character with a horned bee-shaped head and a body covered with some suggestive protuberances. Looking toward the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Clark Heinrich points to mushroom-shaped anomalies drawn from alchemical texts, illuminated manuscripts, and bronze panels from medieval cathedrals. Giorgio Samorini has offered similar speculations about the occasional “mushroom trees” found in early Christian art. Even the modern commercial images of Santa Claus—a magical figure in red and white clothes who flies through the air and lives in the frozen north—has been interpreted as residue of Siberia’s Amanita shamanism.

Yet those who are looking for mushrooms may simply be more inclined to find them. Images deceive. The shapes on the Tassili figure may be fattened arrowheads, or the sort of abstract designs that permeate rock art around the world. Medieval iconologists identify the spindly mushroom tree on the oft-mentioned bronze panel from Hildesheim as a stylized ficus. For true believers, the fragmentary nature of this evidence simply confirms the sneakiness of the cult. Either way, there is a great irony in taking mushroom shapes found in art literally, as unambiguous evidence for the existence of psychedelic magico-religious rituals along the lines of the ones Wasson found in Oaxaca. The message that the mushroom delivers to the eye of the beholder may suggest another story: that appearances themselves are a trickster, a glamour, a phantasm. Now you see it, now you don’t.

**

There is another way to capture the ambiguous appearance of the mushroom, and that is simply to illustrate them as accurately as possible. This is the tradition of natural science, and as far as mushrooms are concerned it goes back at least to a Renaissance botanist named Clusius, who illustrated and described a number of Hungarian mushroom groups in his 1601 monograph Fungorum in Pannoniis Observatorum Brevis Historia. Images as well as words were always key in these texts, and the crude wood-block engravings in Clusius’ book were based on gorgeous watercolors by an unknown hand. Over a century later, Pier Antonio Micheli published his exhaustive Nova Plantarum Genera; seventy-three plates accompanied the book, in which Micheli described the mushroom’s spore-happy reproductive cycle for the first time. In English, James Sowerby published three volumes (plus a supplement) of his Coloured figures of English fungi or mushrooms around the turn of the eighteenth century, while the Frenchman Émile Boudier weighed in a hundred years later with the lithographs for his massive Icones Mycologicae. In all these botanical studies, science is intertwined with art, and therefore with imagination, since even the most exacting quest for visual accuracy is compelled by the nature of the mushroom to delineate the weird and wonderful.

Psychedelic species regularly pop up in these collections, especially the colorful fly agaric, while Sowerby became the first to warn about the intoxicating properties of Psilocybe semilanceata, also known today as Liberty Caps. But proper psychedelic field guides did not begin to appear until the early 1970s, when intrepid North American mushroom geeks started turning the expanded consciousness crowd on to the fact that cousins of Mexico’s legendary magic mushrooms grew on home turf. The images and information that accompanied these early efforts was often inaccurate, and as the field guides improved, they tended to back up their data with photographic literalism rather than artistic illustration. While Wasson’s Life article was accompanied by Roger Heim’s glowing watercolors of various Psilocybe species, and charming drawings packed Richard Evans Schultes’ highly-illustrated 1976 A Golden Guide to Hallucinogenic Plants, the era of scientific mushroom art was beginning to wane. When Paul Stamets published his definitive Psilocybe Mushrooms & Their Allies in 1978, it identified specific species only through full-color photographs.

The seventies were also the decade that the mushroom became established as a central visual icon of the counterculture. Rock art posters by Rick Griffin and Stanley Mouse included the little critters, as did underground comics by Vaughn Bode and flyers for shows (like San Fernando Valley’s Magic Mushroom club). One notably delightful fungal fantasy appeared in the gatefold of the Allman Brothers’ 1972 double album Eat a Peach. Pathetically small in the CD reissues and nonexistent in iTunes, the image unfurls as an enchanted but down-home landscape of humanoids happily sharing their space with dozens of bejeweled mushrooms in various shapes and sizes—a giddy comic-book otherworld that simultaneously references Bosch, Mexican mural art, and the album covers of Mati Klarwein, not to mention the millions of stoned pen-and-ink doodles that were being cranked out in home-rooms across the land. Twenty years later, when rave music resurrected a psychedelic culture of trance dance and inner-eyelid imagery, mushroom iconography exploded once again, becoming an underground logo of transpersonal consciousness that popped up on party fliers, CD covers, and t-shirts.

On the one hand, these countercultural images are simply the latest iteration of the mushroom’s perennial association with mystery and enchantment. This is the same visual tradition that placed Lewis Carroll’s smoking caterpillar on a mushroom, that packed toadstools into Victorian fairy paintings, and that drove the dancing Amanitas in Disney’s Fantasia. But countercultural shroom images are more than storybook icons—they also symbolize the biological host, the actual organic vehicle of the very same visual consciousness that gives so many of these images their wobbly, organic edge. Form becomes content becomes form. Just look at the beautiful line drawings that the ethnobotanist Kat Harrison created to accompany Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower’s Guide, the path-breaking 1976 underground handbook of mushroom cultivation written pseudonymously by Terence McKenna and his brother Dennis. Harrison’s images are charming and impish, but they are also sensitive and accurate—a naturalist’s response to the seemingly supernatural gifts of mushroom consciousness, a mind state where science and imagination became allies united on the plane of appearances.

Arik Moonhawk Roper’s Mushroom Magic is another manifestation of that alliance. On the one hand, the book you hold resembles a typical botanical guide. All the species named and pictured are the real deal, and they are all packed to the gills with some manner of psychoactive alkaloids. At the same time, Roper has allowed the spirit of the mushroom to alter and enhance his illustrations of their bodies. Colors are intensified into hallucinations, while various lines and shapes—the brims of the caps, the flare of the stems—have been exaggerated. Roper’s aim is not to turn mushrooms into caricatures but to reveal their character, to blend the inner and outer worlds. His mushrooms reveal themselves as much for what they do as for what they are. So don’t attempt to use Mushroom Magic as a traditional field guide—unless the pastures you are exploring are the fields of perception, of mind, of spirit.

Roper is the ideal supernaturalist for the task. (And Moonhawk is his given middle name, by the way.) A native New Yorker, born in 1973, Roper trained at the School of Visual Arts before going freelance as an illustrator and graphic designer. He established his name creating strange and evocative LP and CD covers for a bands like High on Fire and Sleep, who are known for dark and gnarly witchery that, like Roper’s visions, pull you in and under. Roper has worked on poster design, animation, and a t-shirt or two, but his work remains devoted to a singular vision of meaty psychedelic otherworlds and their spectral inhabitants. With Mushroom Magic, Roper pushes the conventions of fantasy illustration towards an extreme of mulchy and daemonic pop. One senses the influence of early seventies fantasy, poster, and comic book illustration—of Vaughn Bode, Ralph Bakshi’s Wizards, Corbin, Roger Dean, and Heavy Metal magazine. But this ambiance is only a gateway into deeper and older currents of the imagination. The nimbus of nostalgia that hovers around his work is really a longing for the enchanted world of nature itself. Through Roper’s magic images, this ancient fairyscape—whose invisible spores lie everywhere—begins to germinate again, reappearing before your very eyes.