I had a delightful synchronicity go down recently, and I want to tell the tale. Last December, I went to a week-long meditation retreat hosted at the Mount Madonna Center, a spiritual yoga community I really should have included in my 2006 book The Visionary State, an architectural tour of California’s spiritual and religious landscape. Mount Madonna was founded in the early 1980s by Baba Hari Das, an Indian guru and proponent of Ayurveda and hatha yoga who had relocated to the States the previous decade. Hari Das was a student of the great Neem Karoli Baba, the giggling, lounging saint whose famous Western devotees included the famous Ram Dass (who talks about Hari Das in his classic Be Here Now), the wildman Bhagavan Das, the Buddhist teacher Surya Das, and the mystic pop stars Krishna Das and Jai Uttal, the latter of whom seems to have broken ranks with the whole Das thing.

Baba Hari Das, who died in 2018, took a vow of silence in the 1950s and stuck to it. Alongside his many books, he communicated by marking up a small slate chalkboard now included in an informal shrine nestled in Mount Madonna’s dining room. In the early 2000s, the guru oversaw the construction of the Sankaṭ Mochan Hanuman Temple, which is dedicated to South Asia’s exuberant monkey-man god. It’s a lovely place, at once playful and old school, open to the elements and bedecked with carpets. A charming waterfall feature stands nearby, topped with the bull Nandi; the benches that surround the small Ganesha shrine at the foot of the waterfall are flanked by large cobra statues, their open mouths hovering at eye level as you sit, ready to spit. Every morning, Hanuman is awakened with chants and bells, and every night he is put to bed in similar measure.

Despite the meditation retreat’s busy schedule and secular sensibility, many of us wound up spending a goodly amount of time in the temple, chanting, receiving aarti and prasad, and basically hanging out with the Hanuman vibe. During one afternoon talk, the retreat leader Michael Taft — another co-conspiritor at the Alembic — reflected on the god, who was the central deity in the Tantric Hindu tradition that he pursued obsessively for many years in both India and America. An archetype of the loving devotee and tireless servant of God, Hanuman is also, as Michael emphasized, a simian superhero, a kind of macro Mighty Mouse who can change shape, carry mountains, and, as son of the Wind, fly faster than a speeding bullet.

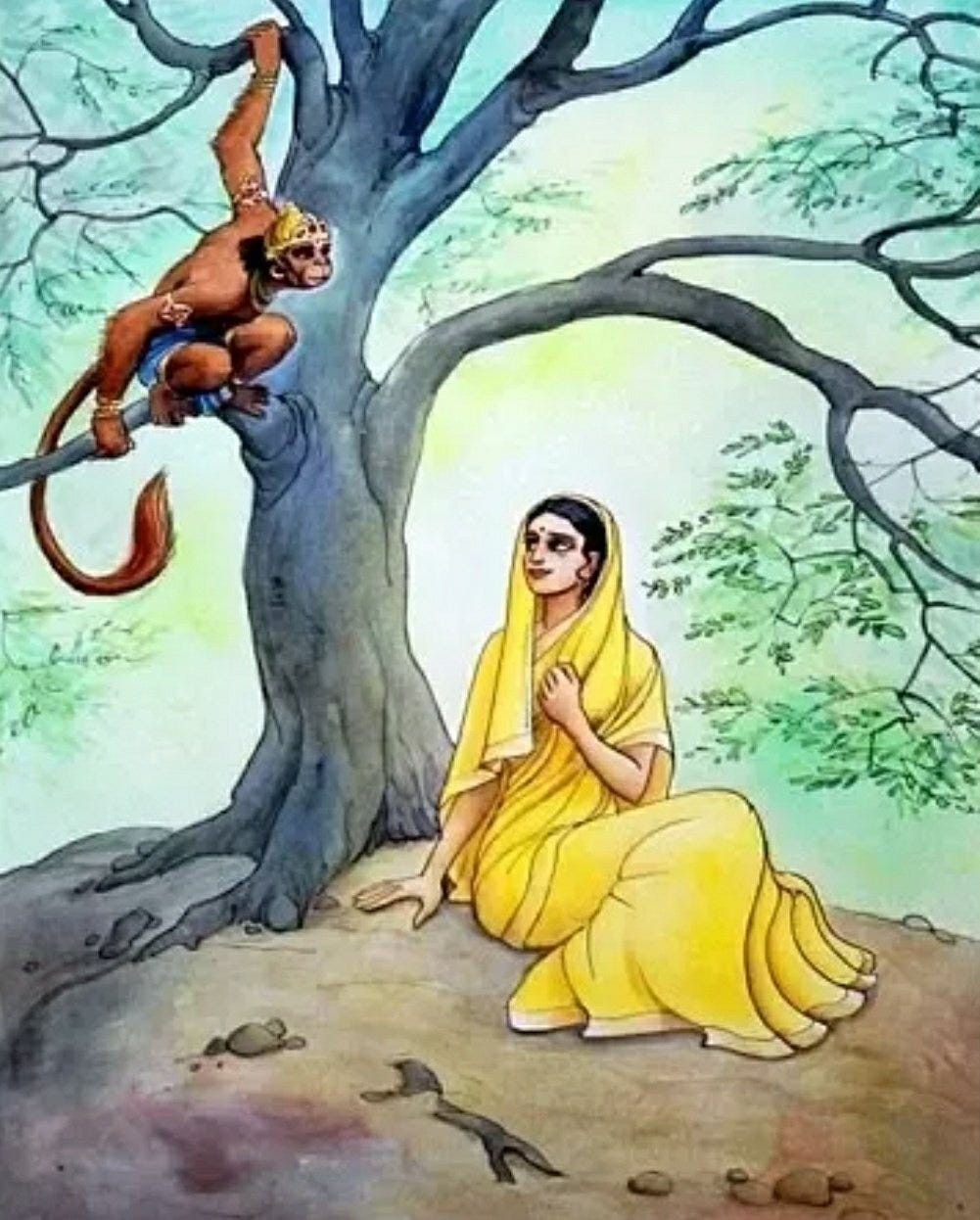

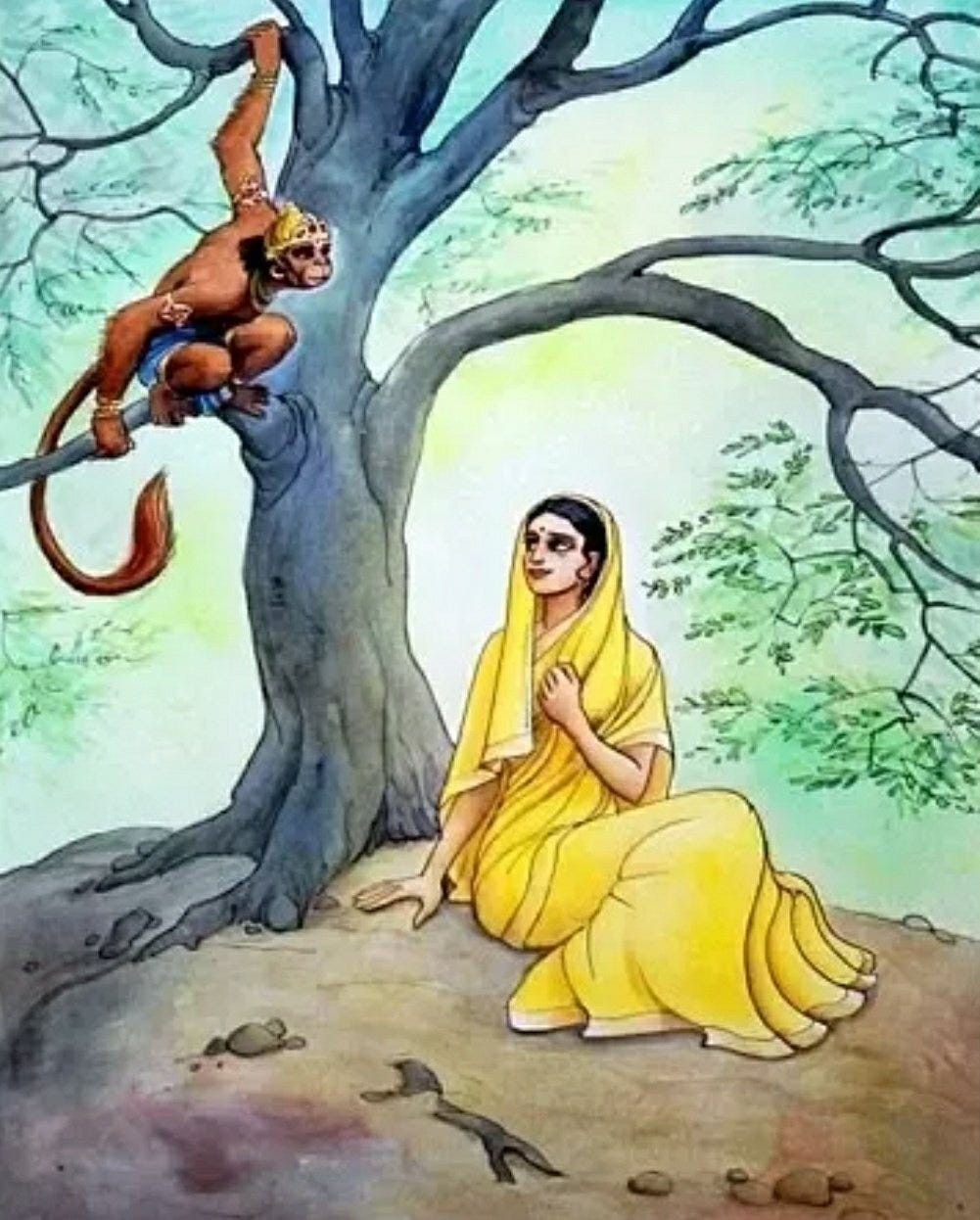

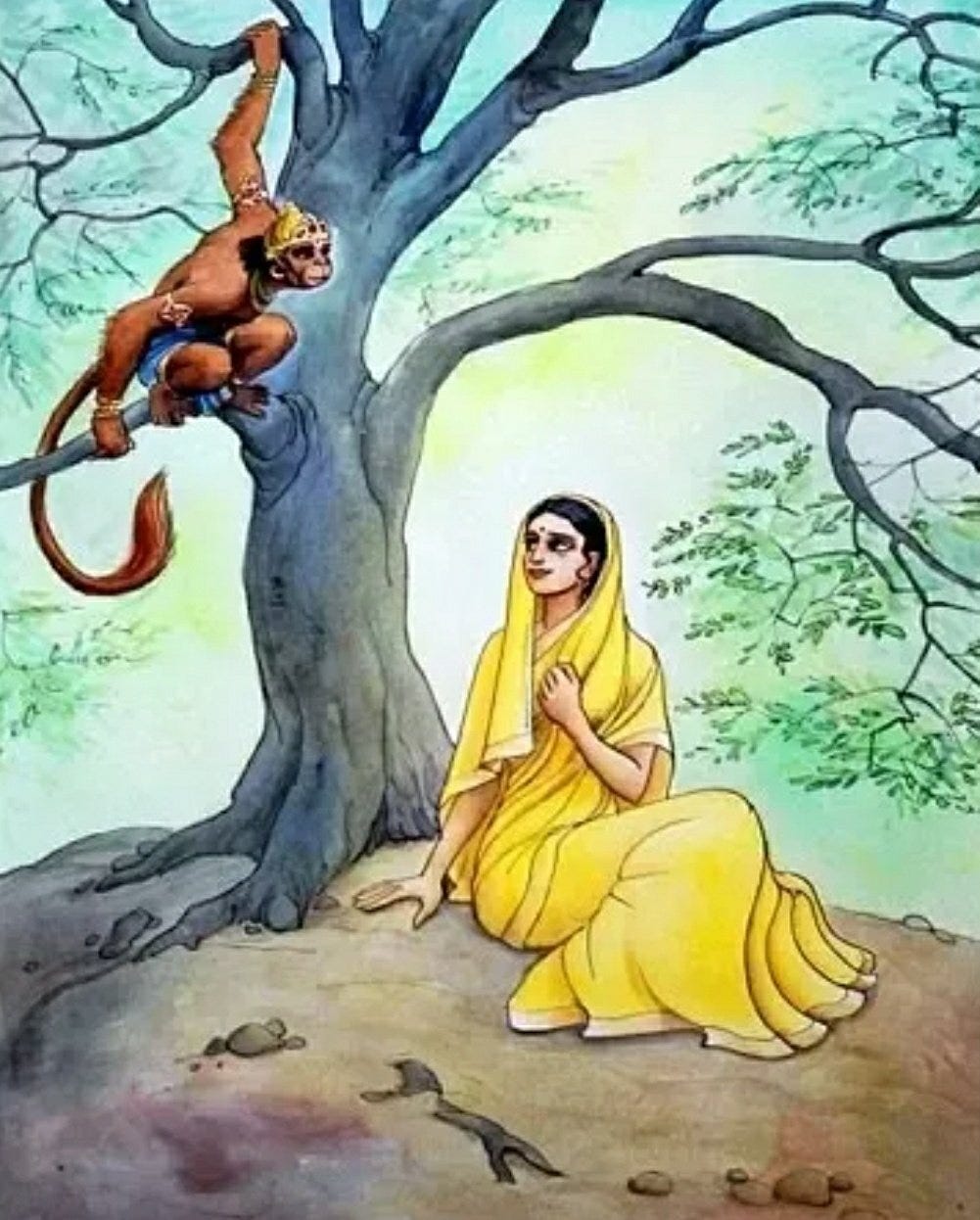

Michael focused on Hanuman’s exploits in the Sundara Kanda, the “beautiful chapter” of Valmiki’s classic Ramayana. About as central to Hindu culture as anything, the Ramayana tells the famous tale of the lordly mortal Rama and his wife Sita, who is abducted by the demon Ravana, a multi-headed rakshasa king, and eventually rescued by her noble husband and Hanuman’s army of monkeys. In the Sundara Kanda, Hanuman flies over the sea to Ravana’s island kingdom of Lanka to find Sita. Michael drew our attention to a specific incident in the chapter, when Hanuman, now shrunk down smaller than a cat, finally discovers Sita in a fabulous garden alongside Ravana’s palace. Surrounded by rakshasi, demon women who urge her to submit to Ravana’s desires, Sita is so sad she is considering suicide.

Hidden in the trees, Hanuman makes his presence known to Sita, not by introducing himself, but by whispering the story of the Ramayana, the same story we are also reading (or hearing). Intrigued, Sita looks up to glimpse the monkey in the trees, but wrestles, in a way common to Indian metaphysics and folklore alike, with the problem of illusion. Is this little monkey an evil dream, or a hallucination, or a concrete reality? Despite Hanuman’s true speech, she comes to believe that he is actually a magical snare conjured by the cruel Ravana. To dampen her doubts, Hanuman shows her the ring that Rama had given him for just such an occasion. Sita is overjoyed, knowing that she has been found at last and sure that she will be rescued by Rama soon.

A few weeks after the retreat I found myself in the basement of City Lights bookstore in North Beach. I wandered over to their small but excellent mythology section, looking for a Ramayana. Michael had recommended the William Buck version, which is not a proper scholarly translation — Buck knew little Sanskrit — but a colorful retelling popular among old hippie seekers as well as Michael’s fellow Western tantrikas. I didn’t find that edition, but I did come across Robert Goldman’s complete English translation, a massive 960-page scholarly tome. I picked up this doorstep, quickly scanned a page towards the end to get a sense of the basic readability of the typeface, and then opened the book at a random page towards the middle and began to read in earnest. And the page I opened to described the exact moment in the garden when Sita first glimpses Hanuman after hearing his voice through the leaves.

Looking sideways, up, and down, she spied at last the inconceivably wise son of the wind god and minister of the lord of the monkeys. He looked like the rising sun.

A radiant image, that, and one whose rays had just zapped me right in the eye, lighting up that basement room in North Beach with a serendipitous flash of Impossible communication.

In his wonderful book You Must Change Your Life, which deeply influenced how I think about religion, Peter Sloterdijk describes a moment in modern spirituality that he ties to an emerging “message ontology.” His primal scene here is Rilke’s confrontation with the headless torso of Apollo, an encounter that catalyzes the famous line that Sloterdijk lifted for his book. In this encounter, the broken statue of a past God is still able to speak to the poet; “the god in the stone constitutes a thing-construct that is still on air.” In this instance, even though the moment of immersion in tradition has passed, “being itself is understood as having more power to speak and transmit, and more potent authority, than God, the ruling idol of religions.”

This is what still gives books a kind of magical potential. Over the decades I’ve had a number of striking book synchronicities, events I remember and categorize separately from intentional bibliomancy or the sort of “random access” reading one performs with the I Ching. A few of these literary synchros have involved — surprise, surprise — the work of Philip K. Dick, whose novels and stories also include all manner of living books and I Ching analogs. Before delivering my first public lecture, in 1990, on “The Postmodern Gnosis of Philip K. Dick,” I had prepared pages and pages of notes. Five minutes before the talk was set to begin, though, I realized I had neglected to include a short and sweet definition of Gnosticism. In anxious, last-minute desperation, I grabbed my dog-eared paperback copy of Dick’s Valis and, opening the book to a random page, fell immediately upon:

This is Gnosticism. In Gnosticism, man belongs with God against the world and the creator of the world (both of which are crazy, whether they realize it or not).

In my book — heh heh — these sorts of coincidences help us to to recognize something true about synchronicity in general: it always has a semiotic component, and therefore can be diagrammed as a kind of message. Even when the uncanny juxtaposition that makes us laugh or freak out takes place outside of language, it depends on objects that behave with the slipperiness of signs — a word, a pun, a symbol, a glyph. Because they literally “take place,” emerging in theatrically charged locations of space-time, these signs are also signals, though the signals themselves are peculiarly layered.

There is the rebus-like message scrawled by the event itself, the coincidence that lifts its elements ineluctably out of ordinary causality and into a new meaningful arrangement. At the same time there is a secondary or “meta” announcement: the message that such uncanny signals are possible, and that some heretofore unseen dimension of communication exists, at least momentarily. And yet, while the first level gives you more information than you were looking for, the second level remains curiously empty. A plate of shrimp might be the message, but the sender, let alone the meaning, remains obscure.

With book synchros, the first level of content is right there before your eyes, like PKD’s apposite definition of Gnosticism, which makes it easy for you to read the coincidence as a message. But the meta-message is still up for grabs. Something was guiding my hand as I randomly opened the book, and you are welcome to call it “chance” if that helps you keep it all together. In any case, the nature and purpose of such a guide is, even if you believe in it, necessarily occluded — a classic PKD word — by the nature of the signalling system itself. Synchronicities conjoin furtive signs that both elicit and refuse sense. That is their pleasure and their curse.

But here’s where it gets trippy. In the case of both the PKD and the Ramayana quotations, the duplicitous duplex signal of synchronicity is twisted into the material itself. In PKD’s Valis world of Gnostic communications, the true God can only contact the human soul by penetrating the crazy world in disguise, and effectively jamming the broadcast signals that keep us in the dark of conventional reality. The Gnostic signal pierces the world of ordinary causality exactly the way that, say, a randomly opened page gives a perfect answer to your immediate question.

In the semi-gnostic situation depicted in the Sundara Kanda, Sita is imprisoned in a lovely but ultimately bleak garden ruled by horny demons. When she hears a liberating signal, its source disguised in the trees, she initially doubts a divine invasion is at hand. It’s just my head projecting patterns into a meaningless void, she thinks, or worse, a demonic ruse. She can’t accept Hanuman any more than my rationality can accept the possibility that randomly accessing this precise scene out of hundreds of possible pages is a meaningful glimpse of some other order of being. Synchronicities take you to the edge, but no further; the message is received but the source hidden. Beyond the uncanny crackle of the signal you have to make a leap — into faith, perhaps, or maybe paranoid pareidolia.

Sita overcomes her doubts, and takes a step toward true encounter and ultimately liberation. (The physical ring, it’s crucial to note, makes all the difference.) Myself, I was not about to start believing that the Ramayana was talking to me. That sort of literalism is the trap of myth, a trap not unrelated to the fundamentalism that concretizes religious narratives into convictions worth killing for. Here it’s crucial to recall the fact that Valmiki tells us that Rama was born in Ayodhya, whose Babri Mosque was destroyed by a Hindu nationalist mob in 1992, triggering horrible communal violence throughout the subcontinent. Modi was already part of the Ram Mandir (Temple) movement in those years, and recently oversaw the consecration of a new Hindu temple at the site just in time for elections. This is the same geographic literalism that has transformed so many West Bank settlers into vicious maniacs, a militant fire rooted in the unwillingness to read the multiple meanings and ambiguous layers of sacred scripture — the galvanizing but still open signs that proper message ontology unleashes in our direction.

For my part I just started thinking more about Hanuman, a character I’ve had some uncanny dealings with in the past — another story — but whom I have not attended to much for years. Now the monkey-god and his mantras have become part of my meditations. I also tracked down that William Buck Ramayana, which once was an undergraduate staple and so now can be had for a dime a highlighter-marred dozen. It’s an absolutely wonderful book: evocative, playful, phantasmagoric, manic. Buck accurately called his work a “retelling” rather than a translation, but though he compressed the tale a lot, he didn’t smooth it out into a YA novel or a streamlined narrative. There are awkward sutures in the storytelling, curious interpolations, dizzy compressions of time and space, references that hang in the void. Like Evangeline Walton’s delicious rendering of the Welsh Mabinogi, published in full about the time Buck’s Ramayana hit the shelves, it draws from the humanistic pleasures and modern tang of contemporary literary fantasy while retaining the liminal weirdness of myth.

Here for example, is a passage that follows Hanuman as he cruises through Ravana’s demon city of Lanka.

Hanuman saw demons who looked wise and powerful even when drunk and asleep with wine, with women, or with their arms round their beloved bags of gold. He saw army officers with coppery lines of sandalpaste on their bodies, talking and waving their strong arms, stretching tough bows and looking disdainfully at maps and beating their chests and sending out orders — Hurry up! Wait! He saw violent, swift demons who never slept, lying in the dark rolling their dismal staring eyes and wearing earrings of charred bone, all alone in the dead of night. He saw courtesans entertaining the rich; by joyous smiles and long slow side-glances of their eyes they trapped all hearts in loveliness and glamor and made all life a pleasure. He saw young new-married wives with their husbands, held by bashfulness and bliss both at once; and girls sad for separation from lovers dear to their souls, weeping heartbroken. And over all the wind chimes and little temple bells, the hum of mantras being chanted grew louder as the night went on, the very sound of the power of Lanka, filling the air.

I compared this passage to Goldman’s translation, and while most of the elements come from the original, the passages there lack Buck’s pulse and slightly feverish fabulosity. In compressing the narrative, he rendered its colors denser, and more magnetic, especially for modern readers.

Buck was also happy to excise stuff he didn’t like — particularly the notorious self-immolation scene at the end of the narrative, when Sita, the victim of a hometown whisper campaign questioning her fidelity, proves her chastity to Rama by stepping into the sati fire. Buck just cuts that shit right out. Today’s militant defenders of Hindu tradition, perhaps relying on the post-colonial tools favored by so many nationalists and populists these days, would likely attack Buck for appropriating and willfully distorting his non-European source. But here it’s good to remember that literally hundreds of versions of the Ramayana exist in Asia. (For more on these various Ramayani, Melvyn Bragg is your man.) Many of these parallel narratives appear to be similarly troubled by the whole wife-burning proof-test thing, which some scholars believe is a later interpolation anyway. There are versions that just drop the whole incident, while others pull the Gnostic docetism card: the Sita who goes to Lanka and then steps into the flames is actually a “Maya Sita,” an illusion crafted by the god Agni to protect the real woman. Traditions are always appropriating and regurgitating themselves, particularly in the Indian subcontinent. The fact that Buck’s retelling shines is not some white triumph but a testament to the propulsive creativity of the Ramayana itself, one of those living stories that will ride Earthlings unto doomsday, a tale strong enough to possess and inspire an American sahib.

I was also pleased to discover that Buck was a Burning Shore man, which somehow didn’t surprise me. Though born in Washington, D.C., in 1933, he was the scion of a wealthy and well-established Marin County family whose patriarch was the first rancher to refrigerate fruit for transport. Buck lived in Marin and later in Vacaville, where he is buried, and he also hung around Sausalito’s bohemian houseboat scene in the early 1950s. When he met his future wife Jane, she was married to the poet, painter, and media artist Gerd Stern, who lived in a repurposed Navy laundry barge not far from the Vallejo, a former ferry that soon housed Alan Watts (and did appear in The Visionary State). All sorts of characters swirling around Buck — Harry Partch, Allen Ginsberg, Kenneth Rexroth, Philip Lamantia. The lovely illustrations for Buck’s two Hindu books (he also “retold” the Mahabharata) come from the hand of Shirley Triest, a pacifist and anarchist who was friends with Jane, and who co-founded the San Francisco Artists and Writers Union.

After running off with Jane, who was considerably older than Buck, they wound up in Nevada, where Buck stumbled across a 19th-century translation of the Bhagavad Gita in a state library in Carson City in 1955. He fell in love with Hindu epic, started to goof around with Sanskrit, and used his considerable funds to insure that a proposed eleven-volume Indian publication of the Mahabharata in English saw the light of day. When he started his own work, Buck never claimed to be translating anything.

My method in writing both Mahabharata and Ramayana was to begin with a literal translation from which to extract the story, and then to tell that story in an interesting way which would preserve the spirit and flavor of the original.

Buck had already returned to California by this point, where he bought a share of Anchor Steam brewery, whose beer Jane was partial to, and moved to Bolinas, already lousy with poets. He wrote, traveled to Asia, banged on kettle drums long through the night. He also seemed to have lost his mind, becoming what his step-daughter described in an extraordinary bohemian oral history as “very far out.” He was institutionalized for a time, and died not long afterwards under weird circumstances, which may have involved a knock on the head. William Buck was only 36 years old, but had still managed to stitch himself into the eternal Tale.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. I have started up paid subscriptions again, though for the moment will not be offering any subscriber-only content. You get what you get. You can also support the publication by forwarding Burning Shore to friends and colleagues, or by dropping an appreciation in my Tip Jar.