Ghost Dancing

One passageway into the sometimes nebulous topic of psychogeography is to remember that landscape is always haunted. Ghosts cling to the folds and vessels of earth and architecture—it is houses that we say are haunted, not texts or minds or flowing rivers. I make no claims as to what exactly these spectres are, whether metaphysical entities or traces of human consciousness or narratives that shape perception. But many of us have encountered land features and structures that are so layered with story and image that they seem to grow enchanted, or at least superimposed—pregnant with absence, with memories that seem to flit invisibly but substantially before you, making space into place.

Few landscapes are as haunted as battlefields, which are supreme sites of psychogeography. Here scores of personal psyches glimpsed their last snapshots of life on earth, and no doubt the vision of some homely shrub or rancid gutter achieved, for some in those last seconds, an incandescent splendor under the sign of the total passing of things. Such light lingers. That is, perhaps, why ghosts are so often associated with particular sites, because the historical flow of those beings, despite their inevitable terminal dates, must somehow continue, even if that continuation is only the afterimage of an unraveled thread, like the blast of air that hurtles forward when a tree falls. But battlefields also gain psychogeographical density because terrain is of such supreme importance in warfare. The need to attack and defend, to see and not be seen, makes the most banal hillock or field of gorse intensely significant—its morphology and sightlines, its coloring and texture, literally a matter of life or death. The choreography of battle magnifies the flows and affordances of landscape more than any other human activity, ritualizing and narrating it, feeding it with the dark sacrifice of blood.

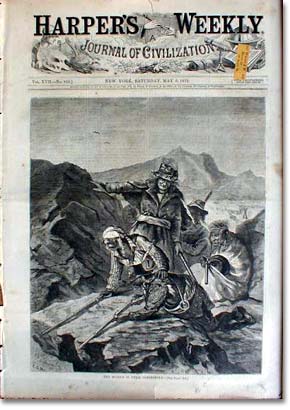

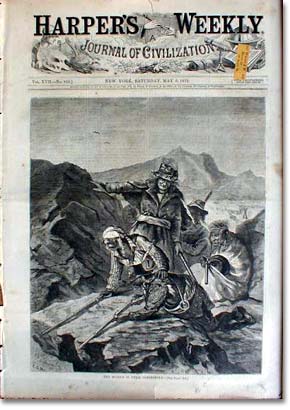

Such were the thoughts flitting about my head when I visited the historical sites at Lava Beds National Monument, which saw the only major Indian war in California’s history, and the only Indian war where a U.S. army general lost his life. (Custer was a general of the volunteer force.) The Modoc War was only one episode in the twenty odd years of intense engagements in the West, as the military forces of the restored Union found new purpose in the vexed territories. Of all these encounters, including the Battle of Little Bighorn, the Modoc War is to my mind the most fascinating and the most poetically resonant. It was the Vietnam of the era, with a well-armed imperialist army first cut down and then bogged down by a small tribe of locals who fought tenaciously and, perhaps most importantly, knew the lay of the land. Throughout the encounter, the Indians used the bizarre and brutal landscape of the lava beds to their own remarkable advantage, holing up inside a natural redoubt known as Captain Jack’s Stronghold, named after the Modoc’s charismatic and ambivalent leader, whose Modoc name was Kintpuash. Killing scores of soldiers in a handful of clashes, and losing only one man, the Modocs held off the army for almost half a year, until they were forced from the Stronghold and, after one more bloody Indian victory, collapsed before the Civil War general Jefferson Davis and his superior numbers. Captain Jack was later captured after being betrayed, and was hung.

The story of the hostilities and their principal players is worthy of Shakespeare, and though Delmer Davies made one OK Western about the war in the 1950s (Drumbeat, with Charles Bronson as Captain Jack), it blows my mind that the Modoc War has not been turned into a film, or at least is not better known. The tale is too intricate to go into here—my favorite source is Arthur Quinn’s excellent Hell With the Fire Out, whose movie-worthy dialogue is drawn from primary sources—but it moves me because features that deeply resonant tale of essentially good men drawn, seemingly inexorably, into the dark karmic machinery of violence. Meacham, the Indian agent, was a thoughtful man who was friends with many of the Modocs, but was nearly slaughtered by them when the Indians assassinated General Canby and a missionary army officer during peace negotiations—an act which turned public sentiment solidly against the Modocs and their legitimate grievances. Mirroring Meacham was Captain Jack, who did not want to fight the whites, and believed it would lead to the tribe’s destruction. But the hot-heads in his band, some of whom slaughtered innocent settlers, forced him into the corner of honor, compelling him to see the fight through to the end. What is Shakespeare-worthy is the fact that some of these very same hot-heads betrayed Jack to the Army, and did not hang.

From the American perspective, the initial encounters were absurd in the bleak sense of the term, a Vietnamish mire marked by tactical errors, dense fog, communication fuck-ups, and ignorance. And much of their challenge lay with the challenging landscape, and especially the natural fortifications afforded by the Stronghold, a craggy and viscous maze of passageways, caves, crenellations, natural firing positions, and defensive walls immediately south of Tule Lake. Today the Stronghold is a well-maintained historical site, and though a fire raged through the spot last August, we were able to visit it on a guided tour. The place is powerful and profound, alive with ghosts, and I was not surprised to hear from our guide that remnants of the Modoc return here every summer for vision quests. Here the Modocs lived and fought with their families at their side, and would have continued to maintain the siege until the army blocked off their access to the waters of the lake and forced a retreat into the high lands. While the army would attack Civil War-style, approaching in a line and building their own battlements, the individual Modocs—well-armed with repeating rifles, many taken from the dead—took advantage of the natural flows and gaps of this savage landscape. Check out the difference between these two positions.

Despite the hard-ass murder of Canby during peace negotiations, the noble and complex character of Captain Jack is no sepia-toned romance. The same cannot quite be said for the tribe’s shaman, known as Curley Headed Doctor, who thoroughly supported the hostilities. The Doctor had power, claiming that his rituals and objects had raised the dense fog that turned the first assault on the stronghold into a disaster, and would continue to protect every single Modoc warrior—an assertion that held true for quite a spell. Given that the figure of the shaman has now attained such a bloated cultural power, it is important to offer up a nasty bad-ass like Curley Headed Doctor as a reminder that these guys could play dark politics like everyone else. What makes the Doctor particularly interesting though is that he was not simply defending the “old ways.” Instead, he was inspired by a new apocalyptic vision of spectral transformation that, over the next twenty years, would grow into the powerful Ghost Dance movement. Though usually associated with the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1891, the roots of the movement lay further west, and much earlier, in the Paiute country that lay along the California/Nevada border. The various influences on the movement are, of course, complex, but the Modoc War is perhaps the first time that the Ghost Dance’s spectral chiliasm made history.

At the heart of the Ghost Dance was the circle dance, a night long shuffle trance that called the ancestors, who were expected to return and unite with the living and somehow participate in the magical destruction of whitey and the paradise that would follow. Today you can still see a ritual space inside the Stronghold where the Doctor reportedly led the trance dances. How much the site itself has been doctored is unclear, but from the psychogeographical point of view, it hardly matters—this dusty lava wheel is itself the endless transtemporal circle we are always entering when we stumble into the jagged gap between landscape and history, mind and matter, ghosts and granite. As I stood before the dancing master’s killing ground, amidst the elegant chaos of the lava flow, beside a chipper forest service guide from New Jersey and a bunch of oldsters navigating the rocky path, it suddenly dawned on me that we are the ghosts.

Previously: Lava Beds