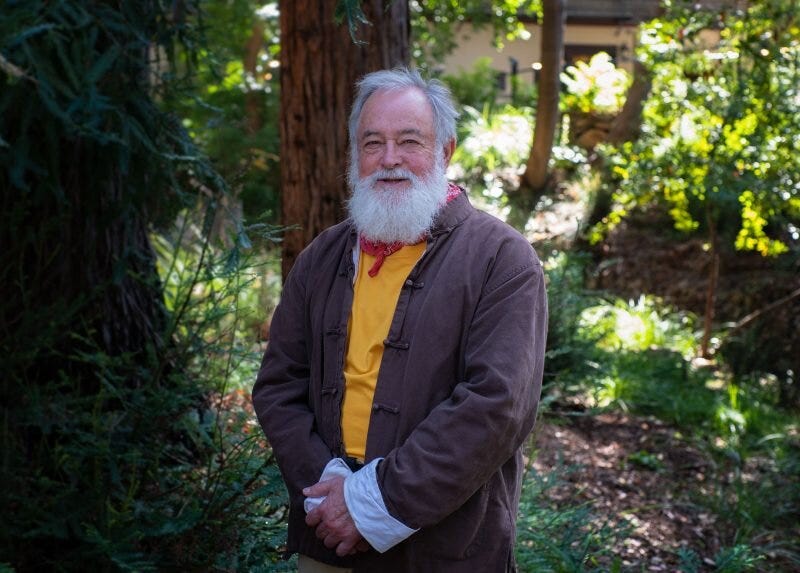

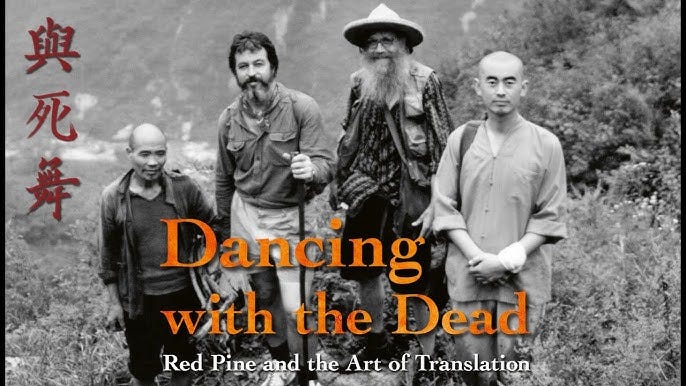

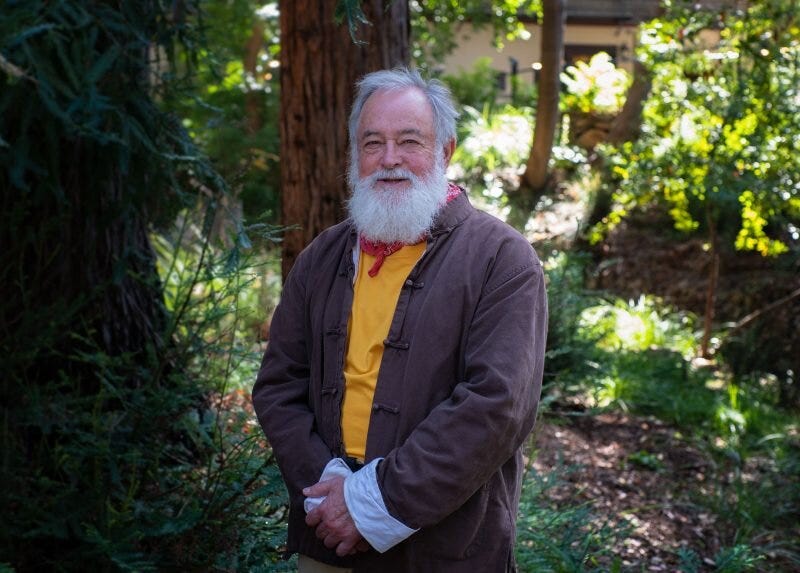

Fooled you! Dancing with the Dead, a new documentary by the filmmaker Ward Serrill, is not actually about the wharf rats, spinners, and syncopated Deadheads who shook their bones to Jerry and the band over the years. Instead, it’s about Bill Porter, aka Red Pine, an American translator of traditional Chinese poetry and dharma, as well as a sometimes travel writer. The doc title describes the almost shamanic character of translation, as Porter explains it, a kind of haunted tango through time and tongue based not on swapping out words from one language to another, but on the careful footwork required to get into the grok behind the words.

I have known Bill for a long time, though we haven’t communicated much recently. The last time I called him I was reading a book from another translator who argued for the Taoist roots of Zen (in Chinese, Chan) concepts and words. This is a very attractive idea to many American Zen practitioners, since classic Taoism is so funky and anti-authoritarian. The argument seemed fishy to me, so I got Bill on the phone. He hadn’t read the book, but said that the practice traditions of Taoism were totally different from the monastic forms that nurtured Buddhism in China. “The invention of tofu and soy sauce had more to do with the establishment of Chinese Buddhism than Taoism.” I couldn’t see him through the phone, but I could tell he was running a gentle grin.

We first met in 2001. Jennifer and I were going to visit the Holy Land that fall, but 9/11 scared us away, and we were scrambling around for an alternative. At that point, I was practicing Zen at Green Gulch Farms, and I met a friendly guy named Andy Ferguson during one sesshin. Andy had recently published a wonderful collection called Zen’s Chinese Heritage, which collates the raw proto-koan tales and aphoristic teachings of the Chinese Chan masters that form the backbone of Zen’s literary tradition. Unlike a lot of Zennies, Andy was down-to-earth and without airs. He actually spoke Chinese, and had been practicing and doing business in the country since the ’70s. He let me know that he was leading a Tricycle magazine tour of Chan temples in China that November, accompanied by the Zen teacher Enkyo Pat O’Hara. Clearly it was meant to be, since Jennifer and I had both started sitting zazen with Pat (as we called her) in the small Greenwich Village apartment she called home while teaching media at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts.

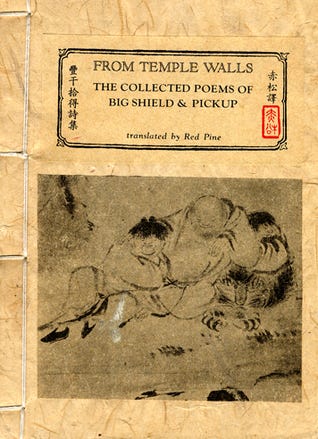

Bill Porter wasn’t part of the tour package but he joined us at the last minute, flying in from his home base in Port Townsend, where he has lived for decades. Bill and Andy had adventured together in the Chinese boonies, hunting down ruined Chan temples and remote religious practitioners. Quests like these had given Bill the subject of one of his most famous and remarkable books, Road to Heaven: Encounters with Chinese Hermits. Sometime in the 1980s, a high-ranking Buddhist priest in Beijing told him that the millennia-long tradition of Chinese hermits was over. Bill didn’t really believe the guy and traveled to the Zhongnan mountains in 1989 to see what he could see. What he found were practitioners young and old, Buddhist and Taoist, taking to the mountains for simple, hard, and solitary practice. Road to Heaven is a great book, and it was a sleeper hit in China; along with a Chinese-language radio show Porter recorded in Taiwan based on his mainland travels, the book gave Red Pine a modicum of fame in China, one that was supercharged a few years ago when Road to Heaven was name-dropped in Ode to Joy, a mega-popular TV show. In Dancing with the Dead, Bill explains that, as someone who happily helped feed his family with food stamps for many years, he was pleased to finally up the quality of his bourbon.

The bus tour was a blast. We traveled to some remarkable places — the Great Wall in the snow, the dizzying Mt. Lu, and a quiet valley monastery where Dongshan founded the Caodong school that Dogen took to Japan as Soto Zen. It is a blessing to pass your feet over the loam of your own practice, which was probably why Thich Nhat Hanh and his crew were also wandering the orchards there. We also visited a few temples associated with Huineng, the legendary Sixth Ancestor whose withered body we glimpsed behind glass. And we hauled our way up Yunmen mountain to Dajue Temple, which had been reconstructed extensively by the remarkable Zen master Empty Cloud in the twentieth century. The place still felt classic, perhaps because of the deep earth wisdom radiating from an ancient ginkgo tree near the temple grounds, one of the most powerful Ents I have had the honor to meet. As we drove into the temple, I looked out the bus window, and the wind blowing through the bamboo forest briefly blew open a gate in my mind, and the trees started swaying in an ordered chaos of pure appearance, their shimmering dance no longer coupled to the usual assumption that something as concrete and abiding as “bamboo trees” lurked behind the flicker.

Choosing to spend a few weeks with twenty-odd Buddhists on a Tricycle magazine tour was, admittedly, a bit of a dice roll. I was already growing a bit tired of American Buddhism at this point, a fatigue that would shortly bounce me out of formal practice for many years. Luckily, our group was not only devoid of snobs or jerks, but included a surprising number of good-humored characters who hunkered down at the back of the bus cracking jokes. It wasn’t all laughs though. For convenience’s sake, we stayed for a few nights in a huge hotel in Nanchang, a city dense with polluted fog and locals who eyed us with suspicion as we poked around the shops (including a convenience store where I purchased my first and only bag of Lonely God potato twists — a gnostic nibble I kept for years on my slacker shrine). Then it dawned on us: the vast sloping atrium of our hotel resounded with the cries of Chinese infants, many of whom we saw in the arms of anxious young Western couples. Nanching, it turned out, was a node in the vast international adoption system that, en masse and in your face (and ears), seemed to us all like a rather grim racket.

One of the finest things about the trip was meeting and spending time with Bill Porter. Dancing with the Dead captures the pith of it: Bill is a twinkly-eyed, adventurous, earthy character devoid of pretense but possessed of a salty and self-reliant Beat charm. He also is a serious tea-head. While I had already tasted proper Chinese tea a few times before, Bill occasionally dragged a handful of us into tea shops to sample the wares, initiating me into the warm and informal pleasures of traditional gongfu, whose artful but casual deployment of uncontained hot water and multiple rinses is worlds away from the uptight if beautiful kabuki theater of Japanese chado. For this tea-head, whose best mornings begin with dank puerh or wild red teas gongfu stylee, Bill’s tea transmission was as potent as any dharma download I got on the trip. In fact, I’d say they were indistinguishable.

One evening, when the tour group was staying in Shaoguan, Andy and Bill invited Jennifer and me to go off with them on an unscheduled hunt for a temple where Huineng supposedly preached his famous Platform Sutra (which Bill subsequently translated for a priceless volume that includes some marvelous and illuminating Red Pine commentary). The temple was being renovated, but after some banging around, we discovered that the abbot was home, and we were invited in. The youngish man was watching some Hong Kong chopsocky show on TV, a pack of Dunhills on a nearby table. He served us all some tea, which was clean and strong and almost telepathic. Most of the conversation was in Chinese, but I did manage to get Bill to translate a psychonaut’s query for the abbot: “How does the mind we have drinking this tea relate to the mind we find in zazen?” The fellow shrugged. “Same thing.”

Dancing with the Dead is animated by a good deal of Bill Porter magic, his twinkly eyes, his dharma bum spunk, his frank and informal turning words. It also tells his tale, which I didn’t know much of, and it’s a good one. Porter’s father was a bank robber who made a small fortune in the hotel business after doing time for a Michigan job. He moved to Los Angeles, where Bill was born to wealth and privilege and serious dysfunction (his father later went bankrupt). Young Bill attended the elite Black-Foxe Military Institute, and spent a lot of time in the Idaho wilderness with cowboy types. He enrolled in university, flunked out, got drafted, went AWOL, got away with it. He eventually found himself studying Chinese and anthropology in New York City, where, after reading Alan Watts, he first tasted the “watermelon Zen” of the local Chinese teacher Shou-Yeh. He dropped out and moved to Taiwan, where he lived in mountains and monasteries, scraped by, wrote poetry, fell in love, smuggled, made chap-books of his translations, and deepened his poetic dharma.

Stylistically, Dancing with the Dead is a solid if unremarkable documentary, and features a number of now familiar features: talking heads, a linear biography — including course-setting childhood trauma — and a number of animation sequences, some of which are nourishing and some of which are silly. We meet some of Bill’s travel cronies, and see him delicately fondle a fourteenth-century manuscript of Stonehouse — a key poet for Red Pine — in the Taipei Central Library. Serrill’s best decision was how to treat the Chinese poetry. Early on, Porter makes the point that poetry in China was traditionally sung, so when individual poems are featured in the doc, we see the English translations on screen while the poems themselves are beautifully and hauntingly voiced by Spring Cheng, a Chinese-American musician.

Interspersed throughout Dancing With the Dead are beautiful clips of a 71-year-old Porter clambering around Chinese mountains talking to hermits. This stuff, it turns out, is from another Red Pine documentary, this one made by a Chinese crew and released in 2015. Available on YouTube as Hermits, the film tracks Porter as he returns to the same Zhongnan mountains he explored for Road to Heaven. He discovers a few traces of his old acquaintances, including a nun who apparently achieved imperishable flesh after passing on. Porter talks with a number of younger practitioners, both Buddhist and Taoist, almost all of whom recognize him. Hermits shows a different Bill Porter than the fellow in Dancing with the Dead: the jokes and mischief take a backseat to a respectful, quiet curiosity. This is Red Pine at work, then, rather than performing “Red Pine.” He mostly asks practical questions of the hermits: how often do they go to town, what they grow, how they deal with tourists, what their daily practice is.

A lot of licensed clips from Hermits appear in Dancing, but folks are definitely encouraged to watch the Chinese film, not just for a fuller picture of Bill Porter, but as a case study in the aesthetic and spiritual range of contemporary documentary making and editing. Hermits has a pretty different vibe. The film is slow, calm, full of long takes, two-shots, and images suspended between poetry and verité — ragged prayer flags, a single leaf of grass pulsing in a stream, fancy modern lanterns. The film is also devoid of camera movement, close-ups, narration, or titles. One monk compares the pace of life in the mountains to the slow motion in film, a slow motion we experience watching Hermits, but not, it must be said, Dancing with the Dead, which proceeds at a much more conventional and accessible pace.

In a remarkable document on IMDB called “13 Commandments”, the three directors of Hermits — Shiping He, Peng Fu, and Chengyu Zhou — explain how painstaking the film-making process was, and not just because it took over three years and 14 trips to the mountains (with Porter himself only present for a brief time). In concert with the willful privation of the hermits they met, the filmmakers also chose to take on many aesthetic and practical constraints themselves. This is just a selection:

1. Zen. Everything moves except the camera position. The dynamic state of men, wind, water, birds, grass and trees contrasts with the static state of the camera. No zoom shots, no pans and tilts, no dolly or crane shots. The balance of composition is pursued, with the steady scenes to reveal inner peace and quietness.

2. Humility. For shooting the hermits, cameramen should adopt only low angle and the static camera position. The camera should be no higher than the cameramen’s heads when they are shooting on their knees. Try to avoid the disrespectful high angle shots, and while shooting the conversations between Bill Porter and the hermits, cameramen should step back or leave the scene once the camera is set and rolling.

8. Silence. There may be awkward situations when the hermits refuse to let the crew in, or are not willing to talk with them, which, however, lead to precious scenes that definitely need to be captured. Moreover, the film let such shots last, in order to brew interesting and profound impression.

10. Vitality. The film does not peruse intentional vitality so as to get rid of the tediousness. In fact, the spontaneous self-mockery and movement are of vivid eastern wisdom and humor. Besides, Bill Porter’s body language is vivid enough.

13. Fast. After going into the mountain, the filming team are forbidden to have alcoholic drinks, meats, scallion, or garlic.

Despite the craggy Zen that results from all this, we see the red dust of the real world lean in. The hermits all complain about tourists and hikers, occasional cars and airplanes cruise by, and massive cities glitter in the near distance at dusk. Some hermits speak to the precipitous decline of the vocation itself, even the internal possibilities of perseverance and discipline and voluntary hardship. But the draw of the ancient way is, for all of that, still compelling, a vision voiced by the ninth-century hermit poet Shih-te (Pickup) in an early Bill Porter translation:

I live in a place without limits

surrounded by effortless truth

sometimes I climb Nirvana Peak

or play in Sandalwood Temple

but most of the time I relax

and speak of neither profit nor fame

even if the sea became a mulberry grove

it wouldn’t mean much to me

Upcoming Events

• I announced this event in my last mailing, but Covid got the better of my co-presenter, so now you get to hear about it again. On Sunday, October 13, starting at 2 pm, I will host Sense Gates: Sound, the first in an occasional series of Sense Gates workshops on sensory awareness at the Berkeley Alembic. For this gathering, I will be joined by the musician and mad field recordist Sam Plattner, and we will focus on the contemplative and aesthetic practice of listening — to sounds, to music, to the environment, to the Void. I’ll start out talking about sacred sound in world mystical traditions, including the extraordinary teachings in the Surangama Sutra. We will link these practices to more experimental and aesthetic approaches to “deep listening,” which will be keyed to a variety of manipulated soundscapes, drones, and musical tracks drawn from the spiritual avant-garde. NOTE: the first hour or so of the workshop, including my introductory talk and a few exercises, will be available for remote streamers.

At 7 pm, after a dinner break, Sam will present Hidden Vistas, an extended sound collage of subsurface field recordings that reveal the otherwise inaccessible resonances and rhythms residing within our urban environments and infrastructure. All of the source material was recorded with geophones, and has been composed, in both manipulated and raw forms, into a sixty-minute sequence exposing the inner vibrational lives of the components of our built environment at all scales, from massive suspension bridges to washing machines. A Sense Gates: Sound ticket gets you in for free, or you can attend the concert separately.

Appearances

• OK, now I know you have had enough of Blotter, but I still had to share the piece about me and the book by Michelle Lhooq, my favorite contemporary drug journalist, who I am happy to say is blowing up (see her recent piece on mainstream wellness shrooming in the Los Angeles Times). For her Double Blind interview (which first appeared on her priceless Substack Rave New World), Michelle interviewed me about some of my favorite blotters from the book.

• Sam Stern is the archivist and podcaster for the Esalen Institute. As a recent outing at the Berkeley Alembic proved, he also drops a mean lecture (he will be back at the Alembic in the New Year). During a recent visit to Big Sur, I was able to sit down with Sam and record this episode of Voices of Esalen. In addition to some Blotter talk, we managed to get into topics like Terence McKenna, John C. Lilly, Dick Price, madness, Stan Grof, the Spiritual Emergence Network, prep-school Deadheads, the Village Voice, and “cannabis thinking.” It’s a good ’un.

Readership Survey

I want to move towards posting more than once a month but I won’t always be able to do longer essays. I am also considering subscriber-only content. I have around three hundred paid subscribers and I would like to more actively honor that support. But what would folks like to see? Relevant archive articles plus new comments? Short best-of lists? Monthly subscriber-only Zoom AMA meet-ups? Shorter essays or reviews? If you have any strong opinions or requests, please let me know at asktheburningshore@gmail.com.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. If you want to support my work, you are encouraged to consider a paid subscription. You can also support the publication by forwarding Burning Shore to friends and colleagues, or by dropping an appreciation in my Tip Jar.