Translated by Nick Hoff

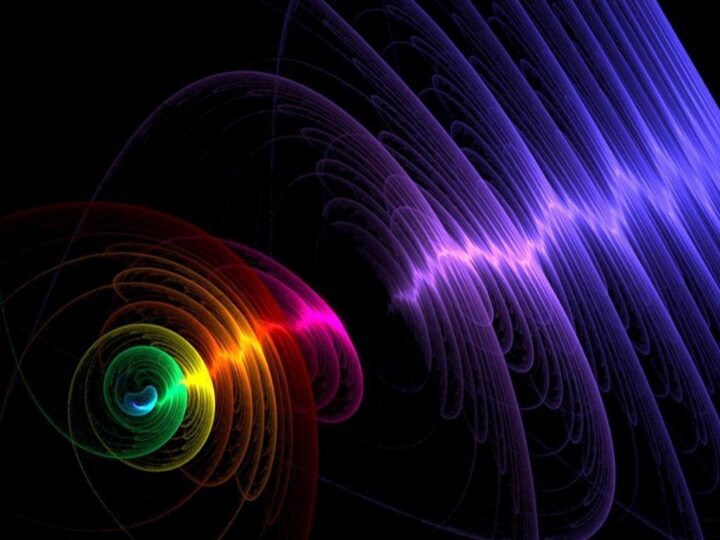

This morning, as I sat on my zafu for a half hour of still and incensed spacetime, I felt a rush of radiance infuse my being, as if my mind had just turned the corner into a momentary clearing of the inner dreck. It took but a moment to realize that it was simply the sun burning through a cloud and bouncing its light against the blank wall my window faces, rays that in turn warmed my half-closed eyelids. A few moments later, the clouds moved in again, cooling my spirit. I saw in that moment how immediately responsive the fluxes of body and mind can be to the dance of climate, at least in the permeable space of meditation. I also realized something way more cool: it was a little fluffy cloud day.

We don’t usually get troops of cumulus clouds in San Francisco, whose skies are generally either grey or blank cerulean blue. (The earthbound fluctuations of fog are another story, licking and skirting the many folds of this hilly city, invading like marauders of mist at sundown and slowly dissipating as the slightly warmer nights fall.) In the early afternoon, I was able to carve out the time for a half hour walk through the lower Haight, with the puff balls drifting listlessly in the near heavens immediately above. As in the morning, the light around me smoothly but suddenly waxed and waned, a quick analog slide between light and shadow, between different registers of a day.

Only this time, the flux took me within, reminding me suddenly of a dream image from two nights before, when J and I experimented with a marvelous oneirogen, a bitter dream-inducing brew called Dreamtime Somalixir made by the wise and trippy spagyrists who run Al-Kemi in Oregon. On that first night, the solution seemed to work wonders on me, usually a hard headed non-dreamer. The most vivid of the fragments that shimmered around me upon waking found me stumbling down a forest path in dusk’s deepening shade. I was shod only in white sweat socks, and as the light dwindled and the damp chill grew I felt an urgent call to return to the safety of the well-lit town above. But I continued plunging into the gloom, until I made a turn to the side and stumbled down into a radiant meadow. The sun was shining, full and warm, and I realized I still had some glorious moments to savor in the late light of day.

And so the weather moves across and penetrates the boundary that usually brackets within and without. But there was another breeze drifting through my walk, and which had perhaps had set the whole dance in motion in the first place: the poems of Friedrich Hölderlin that I have been reading and rereading this last week. I have known about Hölderlin since I studied Romantic poetry and German philosophy in college, but never got around to reading him, partly because he has a rep for being unduly tough on translators. Now Wesleyan University Press has released a new translation by Nick Hoff of the poet’s odes and elegies, metered forms that are less famous than his later free verse (which I guess has received its best treatment in English by Richard Sieburth), but which get some major high fives on the back jacket from the likes of Harold Bloom and Werner Herzog.

What amazing stuff! Fresh, uncanny, and yet nourishing and somehow deeply familiar, at least to this too-late Romantic. With his heart broken at thirty and his mind broken five years later, Hölderlin is a founding archetype as well as bard of the Romantic sensibility. Here he is around the year 1800, mooning over his mistress, Susette Gontard, the wife of his employer:

For they who lend us fire from heaven,

The gods, they grant us holy sorrow too—

So be it. I seem to be a son

Of Earth; made to love, to suffer.

In his introduction, Hoff argues that what makes Hölderlin so readable today is the modernity of his recognition that, as the poet expresses in many elegies, the gods are gone and we are left belated in a disenchanted world, with only our alternately joyous and broken hearts to serve as a half-assed portal back to an ensouled earth. That’s fine as far as it goes. Despite his earnest and even sometimes “naive” lack of irony, Hölderlin reads like one of us. Many of his verses conjured up Rilke, for instance, that great grandchild of Hölderlin, and another sacred modern. Read the following lines, and you can almost see Rilke leaning in over the verse, ghosting it from the future:

But friend, we come too late. It’s true the gods live,

But they live above us in another world.

They move without end and it seems to matter little

To them if we live, that’s how much the gods want to spare us.

For a weak vessel is not always able to hold them,

Man can only bear heavenly fullness at times.

Life becomes then a dream of them.

But while I buy Hoff’s argument in spirit, I can still feel the hot breath of the old gods moving through the less than weak vessels of these poets. No disenchanted trace about it, these guys are touched by spirit, Hölderlin and Rilke both. Rilke’s angelology is incandescent and at times terrifying; I continue to read him as I read Rumi or Lao-tse or the nameless author of the Gnostic tractate “Thunder, Perfect Mind.” And Hölderlin’s paganism, so influenced by that peculiar German idolatry of the Greeks, has what I can only call the authenticity of simplicity. Rather than the tortured sublimity of craggy cliffs and windswept mountain peaks I had for some reason expected to dominate his songs of the Earth, what shines in so many of these odes is a more clean and clear (and Attic) expression of natural forces, especially of sun and air, Apollo and Aether.

Which brings me back to the magic shimmy of the sun and cloud today, for as those fluxes took me back and forth across my skin, from dreamtime to daytime, they also brought me back to Hölderlin, and my stroll through the lower Haight flowed into the walk he wrote of in “The Walk in the Country.” His stroll begins on a gloomy day occasionally laced by sun, who floods the day with his evanescent prize of a joyful heart and an inspired mind, which are, in some sense, all the traces of the actual gods we need.

And therefore I hope, when we start our walk,

And our tongues have been loosened, and the word

Is found and hearts opened, and exalted thoughts spring

From drunken brows, I hope that, together with ours,

The flower of heaven will bloom, and the wide-open

View will open to him who shines down.