The Space Between

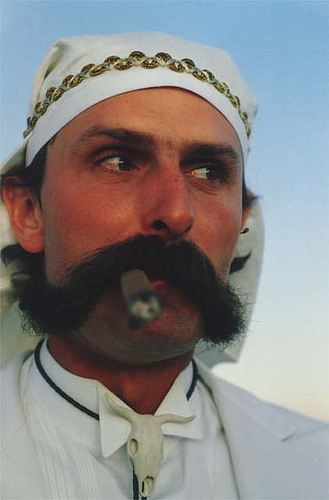

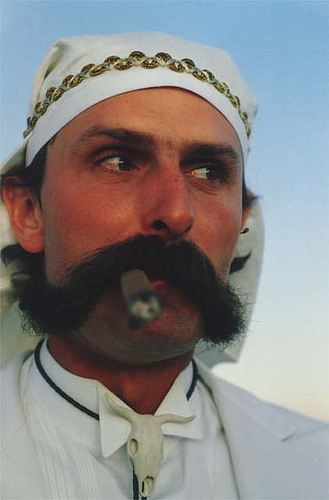

John Law is a tradesman and a prankster and a congenial mustachioed fellow who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. His most famous legacy to date has been Burning Man, an event he co-founded and helped shape as much as anyone, and whose transport to the Black Rock Desert in 1990 he helped facilitate. But Law turned his back on the dusty Mad Max hoedown in 1996 after disagreeing with Larry Harvey about the direction of the event. His last act was to take a spectacular leap from a burning structure during the climax of that year’s Helco shenanigans.

Talk to Law, and he would rather you consider a more varied litany of cultural institutions he has participated and sometimes driven over his thirty-plus years in the Bay: The Suicide Club, Survival Research Laboratories, Seemen, Cacophony Society, Circus Rikidulous, Laughing Squid. These are pretty obscure names to the world at large, but they represent the cream of the crop of the Bay Area’s unique brand of brash punk-ass surrealist prankster collectives. These groups, carrying forward the dada psychedelia of the original Pranksters as well as media-arts clowns like Ant Farm or the Residents, responded to an absurd world by intensifying the absurdity—a hands-on performance art of reality monkey-wrenching that was far too joyful and sarcastic to tolerate the pretense of manifestos or intellectual faddishness.

The Suicide Club, a group which Law joined as a wee transplant in 1977, was perhaps the most notorious of these institutions. Named for a Robert Louis Stevenson story that features a London club whose lot-drawing members come up with clever ways to dispatch their fellow suicides, the adventurer group performed scores of pranks that pushed beyond the boundaries of the law—as well as the psychological comfort zone of its members. Besides practicing Situationist-style détournement on billboards, and spelunking sewers, the group infiltrated the Moonies and the American Nazi Party, and staged manifestations like Clowns on the Bus, in which a series of seemingly unrelated clowns board the Geary bus pretending to go to work.

After Law joined, the Suicide Club also started scaling some of the Bay’s extraordinary bridges, a practice that Law had dabbled in since he was a kid growing up in the midwest, and that later became a raging obsession. He has climbed every bridge in New York City, but still holds the Golden Gate Bridge—the tallest suspension bridge on the planet—as his great and abiding love. Law’s bridge obsession, along with Law’s taste for the weird and his unpretentious straight-shooting vibe, animates The Space Between, a recent collection of three short stories.

Though I dearly hope Law gets around to a proper history of the Suicide Club, here he instead has opted to combine a few of his bridge experiences and obsessions with, of all things, the genre of classic fantasy and horror. The first time me Law, years ago, we talked about Clark Ashton Smith, George Sterling, The Manuscript Found in Saragossa and Melmoth the Wanderer. Law loves Arthur Machen as well, and Machen’s ghost especially lies heavy on the three stories in the volume, in which eerie and nightmarish events intrude on various true-to-life bridge adventures. (A lengthy epilogue includes an unvarnished account of a narrow escape from the authorities following a Golden Gate climb.)

The stories don’t quite possess the narrative propulsion they might, but Law’s combination of adventure memoire and the macabre is fascinating, and he does a great job with atmosphere, and description, both imaginal and realistic. No resident of San Francisco—which Law rightly characterizes as a “gorgeous but provincial city [that] always overestimated its own importance in the scheme of American power, art, and commerce”—can not admire the author’s comparison of its chilly wind and fog to old navigation maps where the “grimacing puffed face of the north wind god” blows frigid blasts along the edge of recently charted seas.

But Law saves his most loving descriptions for the bridges themselves, which he claims are “of all man-made structures, the most sublime:”

All bridges symbolize and embody the concept of movement, travel and at its most compelling the idea of the quest, the search for the grail or simply, the greener grass of the other side. And the icing on the cake for those brave and industrious enough…is the fact that most 20th century bridges, whether arch, cantilever, or suspension type are, in their most basic and elemental manifestation, giant jungle gyms meant for us human chimps to clamber and swing upon. The poetic among the high steel workers live this fact.

And so, evidently, does John Law, a great California poet of the deed.