My journey into the arms of Amma the hugging saint

The amount of “skeptical” hostility directed towards this (IMO) very balanced piece was a stark lesson in the limitations of writing about religious culture in anxiously secular publications.

The Mata Amritanandamayi Center is a cluster of gardens, ponds and institutional buildings nestled in the dry and rolling hills of Castro Valley, a rural area that lies about an hour east of San Francisco. For most of the year, it serves as the sleepy North American outpost for the empire of good works that surround the superstar Indian guru it’s named after, who is best known as Amma. But twice a year, the Mother herself sweeps through, and the place is transformed. For a couple of weeks, thousands of devotees come to sing and meditate and stand in Disneyland-worthy lines to receive Amma’s signature blessing: a great big bear hug.

I show up a little after noon, and Amma has already been at it for hours. Scores of devotees wait in line, while hundreds more mill about the center’s large meeting hall. Charitable booths lie on one side of the space, with a well-stuffed shop of clothes, books and geegaws on the other. Roughly two-thirds of the folks are white, with the rest largely South Asian; like Amma, most are wearing white. The hugging saint herself, a full-bodied woman as brown as the Virgin of Guadalupe, is plopped down in a comfy, low-key thronelike thing at the foot of the large stage that lies at the far end of the hall. Amma is embracing her flock, many of whom believe that she is literally a goddess.

Years of spiritual tourism have taught me that the magic often lies with the devotees rather than the object of devotion, and the scene before me is deeply charming — the spiritual equivalent of comfort food, like a sweet rice pudding scented with rose water. The endless flow of huggees are first asked to kneel, remove any glasses, and mop up their sweaty brows with a Kleenex before being guided into the enveloping embrace of the Mother. After half a minute or so, the devotees are plucked out of Amma’s arms, and the guru hands them flower petals, sacred ashes or maybe a foil-wrapped Hershey’s kiss.

While I am waiting for an audience with Amma herself, I speak with Swami Dayamrita, the orange-robed manager of the Castro Valley ashram. We stand crammed together just to the side of Amma’s nest. A sober, no-nonsense fellow, Dayamrita hails from the southern Indian state of Kerala, where Amma was born to a Dalit fisherman’s family in 1954 and where her principal Indian ashram now lies. Kerala is a traditional center of tantra and goddess worship, but it is also a progressive and well-educated state with a strong, if waning, left-wing culture. As a young man, Dayamrita was an atheist and a filmmaker, and he decided to shoot a damning exposé about his region’s most famous god-person.

While following Amma about he witnessed an event that has since become central to Amma lore. When her village ashram was just starting out, a local leper came in for a hug. Amma embraced him and, in her mad compassion, licked his sores and sucked the pus out of his wounds, which she then covered with sacred ash. “That changed my whole life,” the swami says. “Poor or sick, it doesn’t matter, she embraces them. Shingles, chicken pox, infectious diseases — she does not get them. Only love is exchanged.” Dayamrita gets a call on his cell and departs. Then another fellow in orange robes squeezes through, his hippie glasses and windblown black hair calling to mind a mid-’70s Jerry Garcia. He is Swami Amritaswarupananda Puri, aka “Big Swami,” Amma’s most senior disciple and her main translator, and he collects my questions with an amusingly world-weary, businesslike air.

I ask Amma what she’s doing with all this hugging stuff. Big Swami puts the question into Malayalam for his guru, who is in the midst of double-hugging two Indian teens wearing Izod shirts. Amma launches into her response immediately, with twinkling eyes and a toothy, infectious smile. As she speaks I realize that, Kali or not, she is definitely a firecracker.

“What’s happening here cannot be described,” she says. “It is true communion, pure love that flows, flows like a river. It is pure subjective experience. It’s like somebody trying to explain about drumming. You cannot explain with words. In order to really understand, you have to play a drum or listen to it. It’s a direct experience, a real meeting between hearts. It’s like looking in a mirror and cleaning your face.”

The guru-speak continues. “I’m trying to awaken true motherhood in people, in men and women, because that is lacking in today’s world. Today there are two types of poverty. The first is a lack of basic necessities. The second is a lack of love and compassion. As far as I am concerned, the second is more important because if there is love and compassion then the first kind can be taken care of.”

Though she’ll play the role of the divine Goddess, Amma’s own vibe is informal, earthy and rather spunky. The shoulders on her plain white sari are smudged with the sweat and tears of thousands of strangers, but she seems completely comfortable soaking up the effluence of emotions and desires swimming her way.

“Today people are willing to die for religion, but no one lives in the central truth of religion,” she goes on. “Religion is just the outer shell. The fruit is spirituality. People look at the outer shell and don’t realize the spiritual essence. Spirituality is not different from a worldly life. Spirituality shows how to lead a happy life in the world, to minimize problems and maximize happiness. It is like an instruction manual. What is wrong if you get more happiness from spirituality than worldly pleasures?”

It’s a great question, one that today’s increasingly arrogant atheists have yet to answer. If humans are nothing more than neurologically programmed DNA machines, why not run sacred applications that bring happiness and meaning and active compassion? I start to ask another question, but Big Swami is through. “OK, that’s all,” he says and departs.

Then it’s my turn for some subjective experience. I’m a Californian, so I’m down with hugs, but it is rare to meet a master. As a VIP for the day, I get an E ticket that enables me to skip the hours-long line. I feel kind of lame about taking cuts, and I have a sneaking suspicion that the wait, as is so often the case in this world of desire, amplifies the fun. But there I am, a minute later, headlocked by a perfumed lady who maybe, just maybe, is the mother of the universe.

She rubs my back with her hand as she mumbles into my right ear, a string of syllables I first take to be some esoteric mantra but that gradually reveal themselves to be the homeliest of addresses: “Darling, darling, darling, darling…” I receive no shivering blasts of shakti, the feminine energy cultivated by yogis and sought by devotees. But a warm, childlike nostalgia seeps into my heart, and I have some vague sense of being in the middle of the ocean at night. Then I’m back in the light of the day with a smiling Indian lady handing me a chocolate. I almost immediately reach for my pad to take notes, but Rob Sidon, Amma’s press person, sees me and suggests I “turn off my computer.” So I do.

Innocuous and intimate, the hug is a brilliant gesture for a reputed saint to make — a cosmic download about compassion and connection delivered in a package that’s about as challenging and exotic as a Hershey’s kiss. Amma is not the only one to have embraced the activist power of the hug — last year, Juan Mann’s “Free Hugs” campaign rode the viral spread of a YouTube video into the hearts of millions, while peace organizers recently staged a “Jerusalem Hug” that surrounded the walls of the benighted old city with thousands of people holding hands.

But Amma hugs on a truly global scale, exhibiting a spiritual athleticism that boggles the mind. As the loudspeakers that surround the main meeting hall of the M.A. Center are happy to announce, Amma has hugged more than 26 million people. During her massive 50th birthday celebration in 2003, which was inaugurated by the Indian President Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, Amma cranked through a stadium full of devotees for 21 hours straight while a scoreboard racked up numbers well into the five figures.

Though all this can be seen as some kind of bizarre mass performance art, Amma’s trademark gesture is also a brilliant and quietly subversive transformation of traditional South Asian worship. Hindus, and especially followers of the devotional path of bhakti, have long placed a special emphasis on being in the physical presence of holy beings, whether living saints or revered icons or sacred mountains and rivers. This practice of presence is called “darshan,” and is usually considered a visual or visionary experience (the word means “sight”). But after having a number of powerful goddess visions of her own in the 1970s, a young Amma broke the fourth wall of darshan and started physically embracing those who came to her for succor, spiritual or otherwise.

In India, where traditional mores limit physical contact between women and strangers, Amma’s embrace also announced a liberating and almost feminist activism. As well it should. Amma’s mission, the Mata Amritanandamayi Math, is now one of India’s major humanitarian non-governmental organizations. In the late 1990s, the Math was already the second largest Indian recipient of foreign contributions, totaling $11 million, and her organization has grown dramatically since then. Though its books are closed, materials provided by the Math trumpet scores of large and successful feats, including mass housing projects, disaster relief, food programs, schools, a university and hospitals, one of which is the best research hospital in southern India. The Math contributed $46 million to souls weathering the after-effects of the Southeast Asian tsunami, while the American M.A. Center gave a million bucks to the Bush-Clinton Katrina Fund. While the university and hospital services are not generally free, and the extent of good works may certainly be exaggerated, Amma’s mission has developed the international reputation of actually delivering the goods, and tons of folks have had their lives materially transformed by the organization.

Of course, with abundance comes power, and power means politics. Amma’s flock certainly includes individuals and organizations associated with right-wing Hindu nationalism, or Hindutva. Many Hindutva ministers of state are Amma devotees, including former Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee, and her ranks swell with members of the RSS and VHP, nationalist organizations that have been accused of, among other things, helping foment the bloody Gujarat riots in 2002. These are complex issues, of course, and Amma is the very opposite of fascist demagogue. But many of the liberal Westerners lining up for their hug have no understanding of how their guru plays in reactionary or “fundamentalist” circles in a modern India with a large Muslim population. And the global managers of her brand are perfectly happy to keep it that way.

And Amma is a brand; her organization has a cute registered trademark, good P.R., a snappy slogan (“Embrace the world”), a TV station and an ad campaign that recently plastered the Mother’s mug on billboards and buses across the world. The video shown before her evening gathering at the M.A. Center was essentially an infomercial, though its sentiment was no more manipulative than your average junk letter from the Sierra Club or Amnesty International. What’s amazing, however, is that this juggernaut is sustained by Amma’s own personal example of ceaseless and exhausting activity; even cynics cannot doubt her industry. Eating and resting little, giving out thousands of hugs a day for most of the year, Amma is moving at a supernatural pace.

Amma’s example also creates a culture of self-abnegating service, as followers are encouraged not only to hand over cash, but to sacrifice themselves on the altar of volunteer labor. This is great news for the NGO’s bean counters, but not always so great for the young devotees who are offering “seva,” or service. One ex-devotee, who is wary enough of the organization that she asked me to simply call her Lakshmi, describes the Amma scene as a competitive, back-biting and self-righteous culture where volunteers are encouraged to work beyond the point of exhaustion in order to please Mother. “There is a very strong focus on selfless service,” she wrote in an e-mail. “However, much of the ‘selfless service’ in the West involves assisting people who have enough money to pay for retreats so that there is no paid labor during these programs.” Lakshmi left the organization partly because she “realized that seva might be short for slave labor.”

Another reason that Lakshmi and others have soured on the Amma scene is the growing materialism that feeds the empire. A good quarter of the meditation hall at the M.A. Center, for example, was given over to the Amma Shop, where volunteers in bright orange safety vests oversee a brisk trade in books, mugs, jewelry, clothes, calendars, decals, CDs, unguents, oils and Ayurvedic medicines. Photography and videotaping are forbidden in the hall, but devotees can buy DVDs and photographs of Amma; in some she looks like Queen Latifah. Many objects are advertised as having been blessed — touched — by Amma; I heard one story of a woman who offered a priceless heirloom to Amma, only to see it reappear hours later in the shop. But the most incredible commodity fetishes are the handmade Amma dolls, which were being lugged around by a surprisingly large number of adult women in the hall. These cute and pudgy figures fetched a decent price — $180 for the Cabbage Patch-size ones — and they could be accessorized with colorful silk outfits (blessed by Amma, natch) associated with Durga, Kali and other goddesses.

As a fan of alt-dolls and vinyl figures, I’d have to say the Amma dolls are pretty cool. But for some observers of the spiritual scene, they incarnate nothing so much as spiritual infantilism. Jody Radzik, a 48-year-old graphic designer who writes the muckraking and funny Guruphiliac blog, calls Amma a “space mommy,” which he defines as a guru who fulfills “the function of a cosmic parent for insecure, self-loathing devotees.” A “spiritually informed skeptic,” Radzik nonetheless considers himself a devotee of Kali and a follower of Vedanta, the non-dualist summa of Hindu thought. “Vivekananda described Vedanta very simply. Everyone is God. That means that a single person can’t be more god than any other person. Gurus like Amma pay lip service to the Vedanta while also presenting themselves as special beings who wield magic powers because of their divinity. But self-realization is the opposite of magic — it’s the most mundane thing in their world. It’s always right there right on the end of your nose. These gurus have people looking everywhere but the tip of their nose.”

Amma herself seems to wear her robes lightly; she is a cheery woman of little education who makes no divine claims and carries an air of good-humored humility. But the lore that surrounds her — much of which derives directly from her tight-knit group of core disciples — is redolent with the miraculous. Many devotees, East and West, believe that Amma’s divine shakti can give them children, or fix their marriages, or make them money. One of the first Amma videos that comes up on YouTube shows a reenactment of a young Amma miraculously transforming water into pudding. No one less than Big Swami narrates the clip.

The guru game has many levels. Devotion to divine beings can certainly generate something like miracles in people’s hearts and lives — even if that devotion is nothing more than a placebo effect conjured through a kind of sacred theater. To do their job, gurus must take on all manner of popular projections, but the great teachers also create situations that open up to deeper truths. “Amma’s ability to meet people exactly where they’re at is actually a profound statement of nondualism,” says Greg Wendt, a longtime devotee who lives in a plush Hindufied bachelor pad in Santa Monica, Calif. “It’s really the long view of recognizing people’s journey, and not trying to give people the whole enchilada all the time. Amma has said on a number of occasions, ‘Why teach people Vedanta when all they want is something to eat?'”

Wendt was initially turned off by people “mommy-izing” Amma, but he has since come around. “The whole guru yoga thing is to meditate on the form of your teacher. That’s a core teaching of tantric Buddhism and tantric Hinduism.” From that perspective, Wendt says, even the dolls make sense. “If Amma’s really embodying that path, then she’s not going to stop people from their bhakti ways. There’s a doll there, and you can buy it if you want. She doesn’t care.”

As a successful investment advisor specializing in sustainable and socially responsible capitalism, Wendt has no problems with Amma’s marketing and fundraising machine. Wendt was staying at the Math in Kerala when the tsunami destroyed scores of fishing villages nearby, and he worked on the temporary structures while Amma went toe-to-toe with local officials jockeying for part of the disaster relief pie. Wendt has also been around big-time guru scenes that were far more rapacious. “I don’t even notice that Amma is asking for money,” he says. “But her flow is far more abundant. She’s taking money from crazy housewives and giving it to widows and disaster victims in India. These Westerners are actually having dramatic benefits in their lives, and they in turn are actually housing and feeding the people in India who need it. What a great compassionate way to take from the rich and give to the poor. Even if it were shallow and false, it’s still beautiful.”

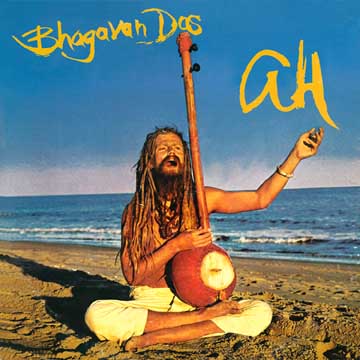

Every guru needs his or her rock stars, and Amma seems to attract guitar gods. The first that came to my attention is J Mascis, the guitarist and singer for Dinosaur Jr., the awesome indie-rock band from the 1980s and ’90s that recently completed a reunion tour. Despite his long hair and transcendent slashing solos, the younger Mascis was the polar opposite of the starry-eyed peak experience junkies that fell for Eastern gurus during the golden age of rock. I profiled him a couple of times, and the impression I had already gleaned from his songs — that he was a mopey and kind of disconnected guy — seemed right on the money. This was no bliss bunny.

Last year, around the time that his album with the Black Sabbath-style hard-rock band Witch came out, Mascis released “J + Friends Sing + Chant for AMMA.” An excellent collection of American neo-kirtans, the record blends Mascis’ whiney indie drawl with dholek and Sanskrit and the occasional monster lead. Unlike the neo-kirtans you might hear in yoga class — those slick call-and-response hymns to Krishna with the funky bass lines and electronic twaddle — Mascis’ god songs sound like the yearning product of, well, a mopey and kind of disconnected guy, “nursing wounds that never end.” I hear you, J: Sometimes only a space momma will do.

Amma’s other fret-board devotee also happens to be the most remarkable person I met during my long day at the M.A. Center. Jason Becker is, or was, what they call a shredder — a master of technically ferocious superfast neoclassical heavy metal guitar. As a young player, Becker had the honor of replacing Steve Vai in David Lee Roth’s band. But Becker soon came down with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis — aka Lou Gehrig’s disease — and his sweep-picking days were done. These days his body is a withered husk strapped down, gaunt head and all, to an elaborate reclined wheelchair replete with tubes and respirators. The 37-year-old Becker cannot speak, but converses using a system of eye movements developed by his father and interpreted by his helper Marilyn, who, like him, is robed in white.

Becker has been following Amma for years, and stickers of her cover the contraption, which is scattered with sacred ash. “She’s always new and inspiring,” he explains. “Love never gets boring.” Becker mentions Amma on his CDs (he continues to compose by computer), and occasionally metal-heads show up at Amma gatherings, curious to check out the guru of their guru. Becker’s forthcoming collection will feature an Indian-inspired tune with Sanskrit and Mayalam lyrics, as well as shred guitar supplied by Joe Satriani.

We chat for a spell about God and guitars, and I cannot relate the peace and impish friendliness that came through this man, who was essentially confined, like all of us, I suppose, to a corpse. I ask him what the best thing was about getting the disease. “That’s easy,” he says. “I got to know God closer, and I got to meet Amma.” He pauses. “I guess I might also be more mature too, but Marilyn would probably disagree.” He laughed with his eyes.

I am reminded of those laughing eyes a few hours later, when Amma once again takes the stage. The curtains part, and she is sitting in an elaborate throne beneath a parasol bedecked with flowers. The plain white sari is gone, replaced with crimson robes, carnations and a crown. This is Devi Bhava, a popular ceremony where Amma visibly performs the presence of the Goddess. The devotees are lined up to the sides of the stage, the front lines of a battalion of devotees whose assault on this plump fisherwoman would last all night. As they surge toward Amma, her face blooms into a radiant, unrestrained glee, and for a spell she looks much less like a cosmic matriarch than a great big kid.