May the Astral Plane be Reborn in Cyberspace

Mark Pesce is in all ways wired. Intensely animated and severely caffeinated, with a shaved scalp and thick black glasses, he looks every bit the hip Bay Area technonerd. Having worked in communications for more than a decade, Pesce read William Gibson’s breathtaking description of cyberspace as a call to arms, and he’s spent the last handful of years bringing Neuromancer‘s consensual hallucination to life — concocting network technologies, inventing virtual reality gadgets, tweaking the World Wide Web. Long driven to hypermedia environments, the MIT dropout has now designed a way to “perceptualize the Internet” by transforming the Web into a three-dimensional realm navigable by our budding virtual bodies.

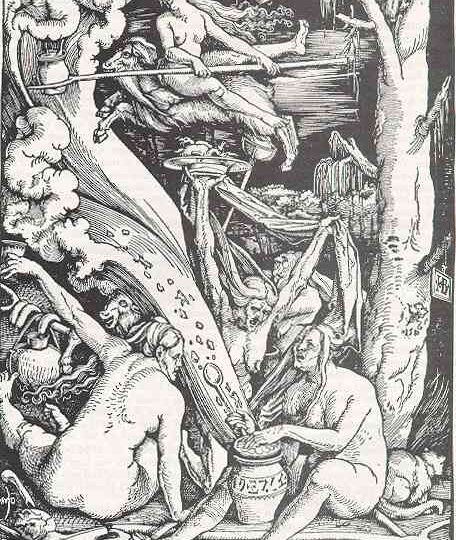

Pesce is also a technopagan, a participant in a small but vital subculture of digital savants who keep one foot in the emerging technosphere and one foot in the wild and woolly world of Paganism. Several decades old, Paganism is an anarchic, earthy, celebratory spiritual movement that attempts to reboot the magic, myths, and gods of Europe’s pre-Christian people. Pagans come in many flavors — goddess-worshippers, ceremonial magicians, witches, Radical Fairies. Though hard figures are difficult to find, estimates generally peg their numbers in the US at 100,000 to 300,000. They are almost exclusively white folks drawn from bohemian and middle-class enclaves.

A startling number of Pagans work and play in technical fields, as sysops, computer programmers, and network engineers. On the surface, technopagans like Pesce embody quite a contradiction: they are Dionysian nature worshippers who embrace the Apollonian artifice of logical machines. But Pagans are also magic users, and they know that the Western magical tradition has more to give a Wired world than the occasional product name or the background material for yet another hack-and-slash game. Magic is the science of the imagination, the art of engineering consciousness and discovering the virtual forces that connect the body-mind with the physical world. And technopagans suspect that these occult Old Ways can provide some handy tools and tactics in our dizzying digital environment of intelligent agents, visual databases, and online MUDs and MOOs.

“Both cyberspace and magical space are purely manifest in the imagination,” Pesce says as he sips java at a creperie in San Francisco’s Mission district. “Both spaces are entirely constructed by your thoughts and beliefs.”

In a sense, humanity has always lived within imaginative interfaces — at least from the moment the first Paleolithic grunt looked at a mountain or a beast and saw a god peering back. Over the millennia, alchemists, Kabbalists, and esoteric Christians developed a rich storehouse of mental tools, visual dataspaces, and virtual maps. It’s no accident that these “hermetic” arts are named for Hermes, the Greek trickster god of messages and information. One clearly relevant hermetic technique is the art of memory, first used by ancient orators and rediscovered by magicians and Jesuits during the Renaissance. In this mnemonic technique, you construct a clearly defined building within your imagination and then place information behind an array of colorful symbolic icons — by then “walking through” your interior world, you can recover a storehouse of knowledge.

The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus gives perhaps the most famous hermetic maxim: “As above, so below.” According to this ancient Egyptian notion, the cosmos is a vast and resonating web of living symbolic correspondences between humans and earth and heaven. And as Pesce points out, this maxim also points to a dynamite way to manipulate data space. “You can manipulate a whole bunch of things with one symbol, dragging in a whole idea space with one icon. It’s like a nice compression algorithm.”

***

Besides whatever technical inspiration they can draw from magical lore, technopagans are driven by an even more basic desire: to honor technology as part of the circle of human life, a life that for Pagans is already divine. Pagans refuse to draw sharp boundaries between the sacred and the profane, and their religion is a frank celebration of the total flux of experience: sex, death, comic books, compilers. Even the goofier rites of technopaganism (and there are plenty) represent a passionate attempt to influence the course of our digital future – and human evolution. “Computers are simply mirrors,” Pesce says. “There’s nothing in them that we didn’t put there. If computers are viewed as evil and dehumanizing, then we made them that way. I think computers can be as sacred as we are, because they can embody our communication with each other and with the entities — the divine parts of ourselves – that we invoke in that space.”

If you hang around the San Francisco Bay area or the Internet fringe for long, you’ll hear loads of loopy talk about computers and consciousness. Because the issues of interface design, network psychology, and virtual reality are so open-ended and novel, the people who hack this conceptual edge often sound as much like science fiction acidheads as they do sober programmers. In this vague realm of gurus and visionaries, technopagan ideas about “myth” and “magic” often signify dangerously murky waters.

But Pesce is no snake-vapor salesperson or glib New Ager. Sure, he spends his time practicing kundalini yoga, boning up on Aleister Crowley’s Thelemic magic, and tapping away at his book Understanding Media: The End of Man, which argues that magic will play a key role in combating the virulent information memes and pathological virtual worlds that will plague the coming cyberworld. But he’s also the creator of VRML, a technical standard for creating navigable, hyperlinked 3-D spaces on the World Wide Web. VRML has been endorsed by Silicon Graphics, Netscape, Digital, NEC, and other Net behemoths, and Pesce’s collaborator, Tony Parisi at Intervista Software, will soon release a 3-D graphical Web browser called WorldView, which will add a crucial spatial dimension to the Web’s tangled 2-D hyperspace of home pages, links, and endless URLs. As Pesce’s technomagical children, WorldView and VRML may well end up catalyzing the next phase of online mutation: the construction of a true, straight-out-of-Neuromancer cyberspace on the Internet.

WorldView first popped out of the ether four years ago, when Pesce was sitting around pondering a technical conundrum: How do you know what’s where in cyberspace? “In the physical world, if you want to know what’s behind you, you just turn around and look,” he explains. “In the virtual reality of cyberspace, you’d do the same thing. But what is the computing equipment involved in the network actually doing? How do I distribute that perceptualization so that all the components create it together and no one part is totally dominant?”

Then Pesce was struck with a vision. In his mind’s eye, he saw a web, and each part of the web reflected every other part. Like any good wirehead, he began to code his numinous flash into a software algorithm so his vision could come to life. “It turns out that the appropriate methodology is very close to the computer equivalent of holography, in which every part is a fragment that represents the greater whole.” Using a kind of a six-degrees-of-separation principle, Pesce invented a spatial cyberspace protocol for the Net.

It was only later that someone told him about the mythical net of Indra. According to Chinese Buddhist sages, the great Hindu god Indra holds in his possession a net stretching into infinity in all directions. A magnificent jewel is lodged in each eye of the net, and each jewel reflects the infinity of other jewels. “It’s weird to have a mystical experience that’s more a software algorithm than anything else,” Pesce says with a grin. “But Friedrich Kekul figured out the benzene ring when he dreamed of a snake eating its tail.”

Of course, Pesce was blown away when he first saw Mosaic, NCSA’s powerful World Wide Web browser. “I entered an epiphany I haven’t exited yet.” He saw the Web as the first emergent property of the Internet. “It’s displaying all the requisite qualities – it came on very suddenly, it happened everywhere simultaneously, and it’s self-organizing. I call that the Web eating the Net.” Driven by the dream of an online data-storage system that’s easy for humans to grok, Pesce created VRML, a “virtual reality markup language” that adds another dimension to the Web’s HTML, or hypertext markup language. Bringing in Rendermorphics Ltd.’s powerful but relatively undemanding Reality Lab rendering software, Pesce and fellow magician Parisi created WorldView, which hooks onto VRML the way Mosaic interfaces with HTML. As in virtual reality, WorldView gives you the ability to wander and poke about a graphic Web site from many angles.

Pesce now spreads the word of cyberspace in conference halls and boardrooms across the land. His evangelical zeal is no accident — raised a hard-core Catholic, and infected briefly with the mighty Pentecostal Christian meme in his early 20s, Pesce has long known the gnostic fire of passionate belief. But after moving to San Francisco from New England, the contradictions between Christian fundamentalism and his homosexuality became overwhelming. At the same time, odd synchronicities kept popping up in ways that Pesce could not explain rationally. Walking down the street one day, he just stopped in his tracks. “I thought, OK, I’m going to stop fighting it. I’m a witch.”

For Pesce, the Craft is nothing less than applied cybernetics. “It’s understanding how the information flow works in human beings and in the world around them, and then learning enough about that flow that you can start to move in it, and move it as well.” Now he’s trying to move that flow online. “Without the sacred there is no differentiation in space; everything is flat and gray. If we are about to enter cyberspace, the first thing we have to do is plant the divine in it.”

And so, a few days before Halloween, a small crowd of multimedia students, business folk, and Net neophytes wander into Joe’s Digital Diner, a technoculture performance space located in San Francisco’s Mission district. The audience has come to learn about the World Wide Web, but what they’re going to get is CyberSamhain, Mark Pesce’s digitally enhanced version of the ancient Celtic celebration of the dead known to the rest of us as Halloween. Of all of Paganism’s seasonal festivals, Samhain (pronounced “saw-when”) is the ripest time for magic. As most Pagans will tell you, it’s the time when the veils between the worlds of the living and the dead are thinnest. For Pesce, Samhain is the perfect time to ritually bless WorldView as a passageway between the meat world and the electronic shadow land of the Net.

Owen Rowley, a buzz-cut fortysomething with a skull-print tie and devilish red goatee, sits before a PC, picking though a Virtual Tarot CD-ROM. Rowley’s an elder in Pesce’s Silver Star witchcraft coven and a former systems administrator at Autodesk. He hands out business cards to the audience as people take in the room’s curious array of pumpkins, swords, and fetish-laded computer monitors. Rowley’s cards read: Get Out of HELL Free. “Never know when they might come in handy,” Rowley says with a wink and a grin.

To outsiders (or “mundanes,” as Pagans call them), the ritual world of Pagandom can seem like a strange combination of fairy-tale poetry, high-school theatrics, and a New Age Renaissance Faire. And tonight’s crowd does appear puzzled. Are these guys serious? Are they crazy? Is this art? Pagans are ultimately quite serious, but most practice their religion with a disarming humor and a willingly childlike sense of play; tonight’s technopagans are no different. The ritual drummer for the evening, a wiry, freelance PC maven, walked up to me holding the read-write arm of a 20-meg hard disk. “An ancient tool of sorcery,” he said in the same goofball tone you hear at comic-book conventions and college chemistry labs. Then he showed me a real magic tool, a beautiful piece of live wood he obtained from a tree shaman in Britain and which he called a “psychic screwdriver.”

With the audience temporarily shuttled next door for a World Wide Web demo, Pesce gathers the crew of mostly gay men into a circle. (As Rowley says, “in the San Francisco queer community, Paganism is the default religion.”) In his black sports coat, slacks, and red Converse sneakers, Pesce seems an unlikely mage. Then Rowley calls for a toast and whips out a Viking horn brimming with homemade full-moon mead.

“May the astral plane be reborn in cyberspace,” proclaims a tall sysop in a robe before sipping the heady honey wine.

“Plant the Net in the Earth,” says a freelance programmer, passing the horn to his left.

“And to Dr. Strange, who started it all,” Rowley says, toasting the Marvel Comics character before chuckling and draining the brew.

As the crowd shuffles back into the room, Pesce nervously scratches his head. “It’s time to take the training wheels off my wand,” he tells me as he prepares to cast this circle.

At once temple and laboratory, Pagan circles make room for magic and the gods in the midst of mundane space time. Using a combination of ceremonial performance, ritual objects, and imagination, Pagans carve out these tightly bounded zones in both physical and psychic space. Pagan rituals vary quite a bit, but the stage is often set by invoking the four elements that the ancients believed composed all matter. Often symbolized by colored candles or statues, these four “Watchtowers” stand like imaginary sentinels in the four cardinal directions of the circle.

But tonight’s Watchtowers are four 486 PCs networked through an Ethernet and linked to a SPARCstation with an Internet connection. Pesce is attempting to link old and new, and his setup points out the degree to which our society has replaced air, earth, fire, and water with silicon, plastic, wire, and glass. The four monitors face into the circle, glowing patiently in the subdued light. Each machine is running WorldView, and each screen shows a different angle on a virtual space that a crony of Pesce’s concocted with 3D Studio. The ritual circle mirrors the one that Pesce will create in the room: an ornate altar stands on a silver pentagram splayed like a magic carpet over the digital abyss; four multicolored polyhedrons representing the elements hover around the circle; a fifth element, a spiked and metallic “chaos sphere,” floats about like some ominous foe from Doom.

WorldView is an x-y-z-based coordinate system, and Pesce has planted this cozy virtual world at its very heart: coordinates 0,0,0. As Pesce explains to the crowd, the circle is navigable independently on each PC, and simultaneously available on the World Wide Web to anyone using WorldView. More standard Web browsers linked to the CyberSamhain site would also turn up the usual pages of text and images – in this case, invocations and various digital fetishes downloaded and hyperlinked by a handful of online Pagans scattered around the world.

Wearing a top hat, a bearded network administrator named James leads the crowd through mantras and grounding exercises. A storyteller tells a tale. Then, in walks the evening’s priestess, a Russian-born artist and exotic dancer named Marina Berlin. She’s buck-naked, her body painted with snakes and suns and flying eyes. “Back to the ’60s” whispers a silver-haired man to my left. Stepping lightly, Berlin traces a circle along the ground as she clangs two piercing Tibetan bells together 13 times.

With a loud, sonorous voice, Pesce races around the circle, formally casting and calling those resonant archetypes known as the gods. “Welcome Maiden, Mother, Crone,” he bellows in the sing-song rhymes common to Pagan chants. “To the North that is Your throne, / For we have set Your altar there, / Come to circle; now be here!”

How much Pagans believe in the lusty wine-swilling gods of yore is a complex question. Most Pagans embrace these entities with a combination of conviction and levity, superstition, psychology, and hard-core materialism. Some think the gods are as real as rocks, some remain skeptical atheists, some think the beings have no more or less actuality than Captain Kirk. Tonight’s technopagans aren’t taking anything too seriously, and after the spirits are assembled, Pesce announces the “the sacred bullshit hour” and hands the wand to his friend and mentor Rowley.

“Witchcraft evolved into the art of advertising,” Rowley begins. “In ancient times, they didn’t have TV — the venue was the ritual occurrence. Eight times a year, people would go to the top of the hill, to the festival spot, and there would be a party. They’d drink, dance in rings, and sing rhyming couplets.” Today’s Pagans attempt to recover that deep seasonal rhythm in the midst of a society that yokes all phenomenon to the manipulative control of man. “It’s about harmonizing with the tides of time, the emergent patterns of nature. It’s about learning how to surf.”

Samhain’s lesson is the inevitability of death in a world of flux, and so Rowley leads the assembled crowd through the Scapegoat Dance, a Celtic version of “London Bridge.” A roomful of geeks, technoyuppies, and multimedia converts circle around in the monitor glow, chanting and laughing and passing beneath a cloth that Rowley and Pesce dangle over their heads like the Reaper’s scythe.

As a longtime participant-observer in the Pagan community, I join in with pleasure. Trudging along, grasping some stranger’s sweaty shoulder, I’m reminded of those gung-ho futurists who claim that technology will free us from the body, from nature, even from death. I realize how unbalanced such desires are. From our first to final breath, we are woven into a world without which we are nothing, and our glittering electronic nets are not separate from that ancient webwork.

***

In 1985, when National Public Radio reporter and witch Margot Adler was revising Drawing Down the Moon, her great social history of American Paganism, she surveyed the Pagan community and discovered that an “amazingly” high percentage of folks drew their paychecks from technical fields and from the computer industry. Respondents gave many reasons for this curious affinity – everything from “computers are elementals in disguise” to the simple fact that the computer industry provided jobs for the kind of smart, iconoclastic, and experimental folk that Paganism attracts. Pagans like to do things — to make mead, to publish zines, to wield swords during gatherings of the Society for Creative Anachronism. And many like to hack code.

But if you dig deep enough, you find more intimate correspondences between computer culture and Paganism’s religion of the imagination. One link is science fiction and fantasy fandom, a world whose role playing, nerd humor, and mythic enthusiasm has bred many a Pagan. The Church of All Worlds, one of the more eclectic and long-lasting Pagan groups (and the first to start using the word pagan), began in 1961 when some undergrad libertarians got jazzed by the Martian religion described in Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land. Today, you can find occult books at science fiction conferences and Klingon rituals at Pagan gatherings.

Science fiction and fantasy also make up the archetypal hacker canon. Since at least the ’60s, countless code freaks and techies have enthusiastically participated in science fiction and fantasy fandom — it’s even leaked into their jokes and jargon (the “wizards” and “demons” of Unix are only one example). When these early hackers started building virtual worlds, it’s no accident they copped these realms from their favorite genres. Like software programs, the worlds of science fiction and fantasy “run” on stock elements and internally consistent rules. One of the first digital playgrounds was MIT’s early Space Wars, a rocket-ship shoot-’em-up. But the Stanford AI lab’s Adventure game lagged not far behind. A text-based analog of Dungeons & Dragons that anticipated today’s MUDs, Adventure shows how comfortably a magical metaphor of caverns, swords, and spells fit the program’s nested levels of coded puzzles.

Magic and Pagan gods fill the literature of cyberspace as well. Count Zero, the second of William Gibson’s canonical trilogy, follows the fragmentation of Neuromancer’s sentient artificial intelligence into the polytheistic pantheon of the Afro-Haitian loa — gods that Gibson said entered his own text with a certain serendipitous panache. “I was writing the second book and wasn’t getting off on it,” he told me a few years ago. “I just picked up a National Geographic and read something about voodoo, and thought, What the hell, I’ll just throw these things in and see what happens. Afterward, when I read up on voodoo more, I felt I’d been really lucky. The African religious impulse lends itself to a computer world much more than anything in the West. You cut deals with your favorite deity — it’s like those religions already are dealing with artificial intelligences.” One book Gibson read reproduced many Haitian veves, complex magical glyphs drawn with white flour on the ritual floor. “Those things look just like printed circuits,” he mused.

***

Gibson’s synchronicity makes a lot of sense to one online Pagan I know, a longtime LambdaMOOer who named herself “legba” after one of these loa. The West African trickster Legba was carried across the Atlantic by Yoruban slaves, and along with the rest of his spiritual kin, was fused with Catholic saints and other African spirits to create the pantheons of New World religions like Cuba’s Santera, Brazil’s Candombl, and Haiti’s Vodun (Voodoo). Like the Greek god Hermes, Legba rules messages and gateways and tricks, and as the lord of the crossroads, he is invoked at the onset of countless rituals that continue to be performed from So Paulo to Montreal.

As legba (who doesn’t capitalize her handle out of respect for the loa) told me, “I chose that name because it seemed appropriate for what MOOing allows — a way to be between the worlds, with language the means of interaction. Words shape everything there, and are, at the same time, little bits of light, pure ideas, packets in no-space transferring everywhere with incredible speed. If you regard magic in the literal sense of influencing the universe according to the will of the magician, then simply being on the MOO is magic. The Net is pure Legba space.”

Whether drawn from science fiction, spirituality, or TV, metaphors make cyberspace. Though Vernor Vinge’s True Names has received far less attention than Neuromancer, the novella explores the implications of cyberspace metaphors in one of the great visions of online VR. Rather than Gibson’s dazzling Cartesian videogame, Vinge imagined cyberspace as a low-bandwidth world of sprites, castles, and swamps that, like today’s MUDs, required the imaginative participation of the users. Anticipating crypto-anarchist obsessions, the novella’s heroic covens elude state control through encryption spells that cloak their doings and their “true names.”

Some of Vinge’s sorcerers argue that the magical imagery of covens and spells is just a more convenient way to manipulate encrypted dataspace than the rational and atomistic language of clients, files, and communications protocols. Regardless of magic’s efficacy, Vinge realized that its metaphors work curiously well. And as legendary science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke said in his 1962 Profiles of the Future, “new technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

But convenience and superstition alone do not explain the powerful resonance between hermetic magic and communications technology, a resonance that we find in history, not just in science fiction (see “Cryptomancy through the Ages,” page 132). Even if magic is only a metaphor, then we must remember how metaphoric computers have become. Interfaces and online avatars are working metaphors, while visualization techniques use hypothetical models and colorful imagery to squeeze information from raw data. And what is simulation but a metaphor so sharp we forget it’s a metaphor?

Then there are the images we project onto our computers. Already, many users treat their desktops as pesky, if powerful, sprites. As online agents, smart networks, and intelligent gizmos permeate the space of our everyday lives, these anthropomorphic habits will leave the Turing test in the dust. Some industry observers worry that all this popular response to computers mystifies our essentially dumb machines. But it’s too late. As computers blanket the world like digital kudzu, we surround ourselves with an animated webwork of complex, powerful, and unseen forces that even the “experts” can’t totally comprehend. Our technological environment may soon appear to be as strangely sentient as the caves, lakes, and forests in which the first magicians glimpsed the gods.

The alchemists, healers, and astrological astronomers of old did their science in the context of sacred imagination, a context that was stripped away by the Enlightenment’s emphasis on detached rationalism. Today, in the silicon crucible of computer culture, digital denizens are once again building bridges between logic and fantasy, math and myth, the inner and the outer worlds. Technopagans, for all their New Age kitsch and bohemian brouhaha, are taking the spiritual potential of this postmodern fusion seriously. As VR designer Brenda Laurel put it in an in e-mail interview, “Pagan spirituality on the Net combines the decentralizing force that characterizes the current stage in human development, the revitalizing power of spiritual practice, and the evolutionary potential of technology. Revitalizing our use of technology through spiritual practice is an excellent way to create more of those evolutionary contexts and to unleash the alchemical power of it all.”

***

These days, the Internet has replaced zines as the clearinghouse of contemporary heresy, and magicians are just one more thread in the Net’s rainbow fringe of anarchists, Extropians, conspiracy theorists, X-Files fans, and right-wing kooks. Combing through esoteric mailing lists and Usenet groups like alt.magick.chaos and soc.religion.eastern, I kept encountering someone called Tyagi Nagasiva and his voluminous, sharp, and contentious posts on everything from Sufism to Satanism. Tyagi posted so much to alt.magick.chaos that Simon, one of the group’s founders, created alt.magick.tyagi to divert the flow. He has edited a FAQ, compiled the Mage’s Guide to the Internet, and helped construct Divination Web, an occult MUD. Given his e-mail address — tyagi@houseofkaos.abyss.com — it almost seemed as if the guy lived online, like some oracular Unix demon or digital jinni.

After I initiated an online exchange, Tyagi agreed to an interview. “You could come here to the House of Kaos, or we could meet somewhere else if you’re more comfortable with that,” he e-mailed me. Visions of haunted shacks and dank, moldering basements danced in my head. I pictured Tyagi as a hefty and grizzled hermit with a scruffy beard and vaguely menacing eyes.

But the 33-year-old man who greeted me in the doorway of a modest San Jose tract home was friendly, thin, and clean-shaven. Homemade monk’s robes cloaked his tall frame, and the gaze from his black eyes was intense and unwavering. He gave me a welcoming hug, and then ushered me into his room.

It was like walking into a surrealist temple. Brightly colored paper covered the walls, which were pinned with raptor feathers and collages of Hindu posters and fantasy illustrations. Cards from the Secret Dakini Oracle were strung along the edge of the ceiling, along with hexagrams from the I Ching. To the north sits his altar. Along with the usual candles, herbs, and incense holders, Tyagi has added a bamboo flute, a water pipe stuffed with plants, and one of Jack Chick’s Christian comic-book tracts. The altar is dedicated to Kali, the dark and devouring Hindu goddess of destruction whose statue Tyagi occasionally anoints with his lover’s menstrual blood. Other figures include a Sorcerer’s Apprentice Mickey Mouse and a rainbow-haired troll. On the window sill lies the tail of Vlad the Impaler, a deceased cat. Near the altar sits a beat-up Apple II with a trackball that resembles a swirling blue crystal ball.

On one wall, Tyagi has posted the words Charity, Poverty, and Silence. They are reminders of monastic vows Tyagi took, vows with traditional names but his own, carefully worked out meanings. (Tyagi is an adopted name that means “one who renounces.”)

“I just stopped grabbing after things,” he said. “I made certain limitations and assertions on how I wanted to live and be in the world.” His job as a security guard gives him just enough cash for rent, food, and dial-up time.

“For a long time, I had the desire to find the truth at all costs, or die trying,” Tyagi said in a measured and quiet voice. After reading and deeply researching philosophy, mysticism, and the occult, Tyagi began cobbling together his own mythic structures, divination systems, and rituals — an eclectic spirituality well suited to the Net’s culture of complex interconnection. Like many technopagans, Tyagi paid his dues behind the eight-sided die, exploring role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons and Call of Cthulhu. He also delved heavily into chaos magic, a rather novel development on the occult fringe that’s well represented on the Net. Rather than work with traditional occult systems, chaos magicians either construct their own rules or throw them out altogether, spontaneously enacting rituals that break through fixed mental categories and evoke unknown — and often terrifying — entities and experiences.

“Using popular media is an important aspect of chaos magic,” Tyagi says as he scratches the furry neck of Eris, the Doggess of Discord. “Instead of rejecting media like many Pagans, we use them as magical tools.” He points out that Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth, the chaotic magical organization that surrounds the industrial band Psychick TV, would practice divination with televisions tuned to display snow. “Most Pagans would get online and say, Let’s get together somewhere and do a ritual. Chaos magicians would say, Let’s do the ritual online.”

After compiling his original Mage’s Guide to the Internet — an exhaustive directory of mailing lists, ftp sites, newsgroups, and MOOs — Tyagi hooked up with Moonchilde, also known as Joseph Traub, a god of an online MUSH devoted to Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern series, and created an occult MUD called Divination Web (telnet bill.math.uconn.edu 9393). Originally, DivWeb presented a virtual geography of spiritual systems: a great Kabbalistic Tree of Life stood in the center of a wheel whose various spokes mapped out different astrological signs and psychological states and linked up to other realms — Celtic, shamanic, Satanic. Down one path lay an amusement park devoted to religious heresy; another direction would send you down the river of the Egyptian afterlife. But Tyagi found the layout too structured, and now you just log into the Void.

These days, Tyagi cruises the Net from four to six hours a day during the week. “Being online is part of my practice. It’s kind of a hermit-like existence, like going into a cave. I’m not really connected to people. I’m just sending out messages and receiving them back.”

But for MOO-oriented magicians like Tyagi, the Net is more than a place of disembodied information. “Cyberspace is a different dimension of interaction. There’s a window between the person who’s typing and the person who finds himself in cyberspace,” Tyagi explains. “If you’re familiar enough with the tool, you can project yourself into that realm. For me, I start to associate myself with the words that I’m typing. It’s less like I’m putting letters onto a screen and more like there’s a description of an experience and I’m having it. It’s a wonderful new experiment in terms of magic and the occult, and it connects with a lot of experiments that have happened in the past.”

Like some MUD users, Tyagi finds that after logging heavy time in these online realms, he interacts with the offline world as if it were an object-oriented database. “Within the physical world, there are certain subsets that are MUDs — like a book. A book is a kind of MUD — you can get into it and move around. It’s a place to wander. So MUDs become a powerful metaphor to see in a personal sense how we interact with different messages. Real life is the fusion of the various MUDs. It’s where all of them intersect.”

For the Druids and hermetic scholars of old, the world was alive with intelligent messages: every star and stone was a signature; every beast and tree spoke its being. The cosmos was a living book where humans wandered as both readers and writers. The wise ones just read deeper, uncovering both mystical correspondences and the hands-on knowledge of experimental science.

To the thousands of network denizens who live inside MUDs and MOOs like DivWeb or LambdaMOO, this worldview is not as musty and quaint as it might seem to the rest of us. As text-based virtual worlds, MUDs are entirely constructed with language: the surface descriptions of objects, rooms, and bodies; the active script of speech and gesture; and the powerful hidden spells of programming code. Many MOOs are even devoted to specific fictional worlds, turning the works of Anne McCaffrey or J. R. R. Tolkien into living books.

For many VR designers and Net visionaries, MOOs are already fossils — primitive, low-bandwidth inklings of the great, simulated, sensory overloads of the future. But hard-core MOOers know how substantial and enchanting — not to mention addictive — their textual worlds can become, especially when they’re fired up with active imagination, eroticism, and performative speech.

All those elements are important in the conjurer’s art, but to explore just how much MOOs had to do with magic, I sought out my old friend legba, a longtime Pagan with a serious MOO habit. Because her usual haunt, LambdaMOO, had such heavy lag time, legba suggested we meet in Dhalgren MOO, a more intimate joint whose eerie imagery is lifted from Samuel Delaney’s post-apocalyptic science fiction masterpiece.

That’s how I wind up here on Dhalgren’s riverbank. Across the water, the wounded city of Bellona flickers as flames consume its rotten dock front. I step onto a steel suspension bridge, edging past smashed toll booths and a few abandoned cars, then pass through cracked city streets on my way to legba’s Crossroads. An old traffic light swings precariously. Along the desolate row of abandoned storefronts, I see the old Grocery Store, legba’s abode. Through the large and grimy plate glass window I can see an old sign that reads: Eggs, $15.95/dozen. The foreboding metal security grate is locked.

Legba pages me from wherever she currently is: “The next fun thing is figuring out how to get into the grocery store.”

Knowing legba’s sense of humor, I smash the window and scramble through the frame into the derelict shop. Dozens of flickering candles scatter shadows on the yellowing walls. I smell cheese and apples, and a sweet smoke that might be sage.

Legba hugs me. “Welcome!” I step back to take a look. Legba always wears borrowed bodies, and I never know what form or gender they’ll be. Now I see an assemblage: part human, part machine, part hallucination. Her mouth is lush, almost overripe against bone-white skin, and her smile reveals a row of iridescent, serrated teeth. She’s wearing a long black dress with one strap slipping off a bony, white shoulder. Folded across her narrow back is one long, black wing.

I’m still totally formless here, so legba urges me to describe my virtual flesh. I become an alien anthropologist, a tall, spindly Zeta Reticuli with enormous black eyes and a vaguely quizzical demeanor. I don a long purple robe and dangle a diamond vajra pedant around my scrawny neck. Gender neutral.

Legba offers me some canned peaches. Pulling out a laser drill, I cut through the can, sniff the contents, and then suck the peaches down in a flash through a silver straw.

Once again, I’m struck at how powerfully MOOs fuse writing and performance. Stretching forth a long, bony finger, I gently touch legba’s shoulder. She shivers.

“Do we bring our bodies into cyberspace?”

Legba does.

She doesn’t differentiate much anymore.

“How is this possible?” I ask. “Imagination? Astral plane? The word made flesh?”

“It’s more like flesh made word,” legba says. “Here your nerves are uttered. There’s a sense of skin on bone, of gaze and touch, of presence. It’s like those ancient spaces, yes, but without the separations between earth and heaven, man and angel.”

Like many of the truly creative Pagans I’ve met, legba is solitary, working without a coven or close ties to Paganism’s boisterous community. Despite her online presence and her interest in If, the West African system of divination, legba’s a pretty traditional witch; she completed a Craft apprenticeship with Pagans in Ann Arbor and studied folklore and mythology in Ireland. “But I was sort of born this way,” she says. “There was this voice that I always heard and followed. I got the name for it, for her, through reading the right thing at the right time. This was the mid- to late ’70s, and it was admittedly in the air again.

I went to Ireland looking for the goddess and became an atheist. Then she started looking out through my eyes. For me, it’s about knowing, seeing, being inside the sentience of existence, and walking in the connections.”

These connections remind me of the Crossroads legba has built here and on LambdaMOO. She nods. “For me, simultaneously being in VR and in RL [real life] is the crossroads.” Of course, the Crossroads is also the mythic abode of Legba, her namesake. “Legba’s the gateway,” she explains. “The way between worlds, the trickster, the phallus, and the maze. He’s words and their meanings, and limericks and puns, and elephant jokes and -”

She pauses. “Do you remember the AI in Count Zero who made those Cornell Boxes?” she asks. “The AI built incredible shadow boxes, assemblages of the scraps and bits and detritus of humanity, at random, but with a machine’s intentionality.” She catches her breath. “VR is that shadowbox. And Legba is,” she pauses, “that AI’s intentionality.”

But then she shrugs, shyly, refusing to make any questionable claims about online gods. “I’m just an atheist anarchist who does what they tell me to do,” she says, referring to what she calls the “contemporary holograms” of the gods. “It works is all.”

I asked her when she first realized that MOOs “worked.” She told me about the time her friend Bakunin showed her how to crawl inside a dishwasher, sit through the wash-and-rinse cycle, and come out all clean. She realized that in these virtual object-oriented spaces, things actually change their properties. “It’s like alchemy,” she said.

“The other experience was the first time I desired somebody, really desired them, without scent or body or touch or any of the usual clues, and they didn’t even know what gender I was for sure. The usual markers become meaningless.”

Like many MOOers, legba enjoys swapping genders and bodies and exploring net.sex. “Gender-fucking and morphing can be intensely magical. It’s a very, very easy way of shapechanging. One of the characteristics of shamans in many cultures is that they’re between genders, or doubly gendered. But more than that, morphing and net.sex can have an intensely and unsettling effect on the psyche, one that enables the ecstatic state from which Pagan magic is done.”

I reach out and gingerly poke one of her sharp teeth. “The electricity of nerves,” I say. “The power of language.”

She grins and closes her teeth on my finger, knife-point sharp, pressing just a little, but not enough to break the skin.

“It’s more than the power of language,” legba responds. “It’s embodiment, squishy and dizzying, all in hard and yielding words and the slippery spaces between them. It’s like fucking in language.”

“But,” I say, “jabbering in this textual realm is a far cry from what a lot of Pagans do — slamming a drum and dancing nude around a bonfire with horns on their heads.”

She grins, well aware of the paradox. As she explains, our culture already tries to rise above what Paganism finds most important (nature, earth, bodies, mother), and at first the disembodied freedom of cyberspace seems to lob us even further into artificial orbit.

“But the MOO isn’t really like a parallel universe or an alternate space,” legba says. “It’s another aspect of the real world. The false dichotomy is to think that cyberspace and our RL bodies are really separate. That the ‘astral’ is somewhere else, refined and better.”

I hear a call from the mother ship. “I must take my leave now.”

Legba grins as well and hugs me goodbye.

I try to smile, but it’s difficult because Gray aliens have such small mouths. So I bow, rub my vajra pendant, and wave. For the moment, my encounter with technopaganism is done. I’ve glimpsed no visions on my PowerBook, no demons on the MOO, and I have a tough time believing that the World Wide Web is the living mind of the Gaian Goddess. But even as I recall the phone lines, dial-up fees, and clacking keyboards that prop up my online experience, I can’t erase the eerie sense that even now some ancient page of prophecy, penned in a crabbed and shaky hand, is being fulfilled in silicon. And then I hit @quit, and disappear into thin electronic air.

This essay originally appeared in Wired