Klea McKenna’s The Butterfly Hunter

The smartest thing I did when I interviewed the mushroom bard Terence McKenna shortly before his death in 2000 was to ask this inveterate collector of exotica to tell me about his most precious objects. Here is what I wrote for the subsequent Wired profile:

An altar lies on top of a cabinet over which hangs a frightening old Tibetan tangka. With McKenna at my side, the altar’s objects are like icons in a computer game: Click and a story emerges. Click on the tangka and get a tale of art-dealing in Nepal. Click on the carved Mayan stones and hear about a smoking god who will arrive far in the future. Click on an earthen bowl and wind up in the stone age…Gamers know that the most interesting objects usually lie near the obvious ones, and indeed, the real prizes here lurk inside the narrow cabinet drawers: butterflies. Click on these hummingbird-sized beauties and you’ll be transported back 30 years to the remote islands of Indonesia, where McKenna dodged snakes and earthquakes in order to capture prize specimens for the butterfly otaku of Japan.

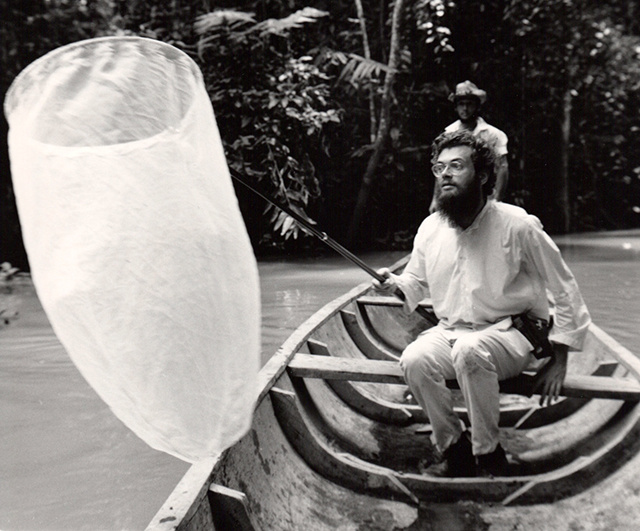

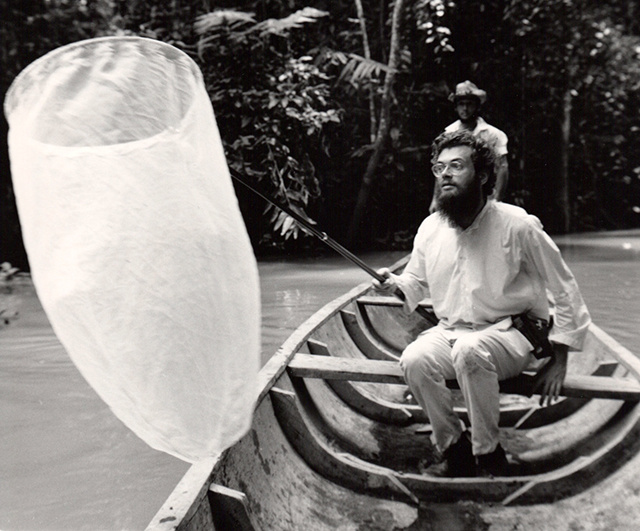

Though known for his witty and mesmerizing ruminations on psychedelics, consciousness, and the onrushing eschaton, McKenna probably considered himself a naturalist more than anything. He loved butterflies, and nursed a life-long obsession with Alfred Russel Wallace, the Victorian biologist, explorer, butterfly hunter, and Spiritualist who, independently of Darwin, came up with the theory of natural selection. As a young freak traveling the globe in the late Sixties, Terence was inevitably drawn to Indonesia, the same biologically riotous archipelago that inspired Wallace’s breakthrough. But McKenna had additional reasons to indulge his lepidopterist desires in these remote islands: a shipment of hashish he had sent to the states from India had been intercepted by the feds, and he was on the lam. In 1969, remote and unhippied Indonesia was a fine place to hide.

Decades later, McKenna shared his love of butterflies with his daughter Klea, the second of his two children. Following her father’s death, Klea wound up with the collection, which was nestled away in various jars, cigar boxes, and South American cookie tins that were in turn packed into an old enamel trunk held together with duck tape. The specimens that McKenna had shown me from the hundred or so that he had spread, pinned and mounted; the rest of his haul—2000 or so—were tucked away inside the various containers, neatly folded into triangular slips of paper marked with dates and place names. In addition to McKenna’s Indonesian scores, the collection also held a number of Amazonian specimens, including some rare and stunning glasswings. These McKenna collected when, still on the lam, he visited Columbia 1971 with his brother Dennis and staged the famously bizarre mushroom-munching “experiment at La Chorrera.”

When Klea—who is now a fine art photographer earning her MFA at the California College of the Arts—first began excavating the trunk in 2007, she discovered that none of the butterfly packets had been opened. As she unfolded the the specimens, she discovered something else: the pieces of paper had their own stories to tell. She photographed about a hundred or so of the specimens, along with their paper wrappings, and turned these images into The Butterfly Hunter, an interactive gallery show and now a gorgeous limited-edition signed artist book available—along with select images from the project—at her website. A remarkable visual meditation on time, loss, and the culture of nature, The Butterfly Hunter is also a fascinating engagement—intimate yet cool—with what Klea described to me as her father’s “fanatical romanticism.”

Klea grew up in the swirling penumbra of Terence’s peculiar shadow, and, like many children of famous and colorful folk, had to consciously define her own creative voice apart from her father’s world. In its first, gallery iteration, The Butterfly Hunter did not mention her father’s name, because she wanted the work to stand on its own merit. It is a mark of her courage that her book takes on Terence’s legacy, and a mark of her success that she does it with such candor and care. Using the violent word “hunter” rather than the somewhat white-washed “collector,” McKenna is well aware of the dark side of her father’s obsession, which she suggests, with good reason, partly grew out of his attempt to emulate his hero Wallace. At the same time, Klea’s fond curiosity with her strange and amazing father’s strange and amazing life radiates through the images.

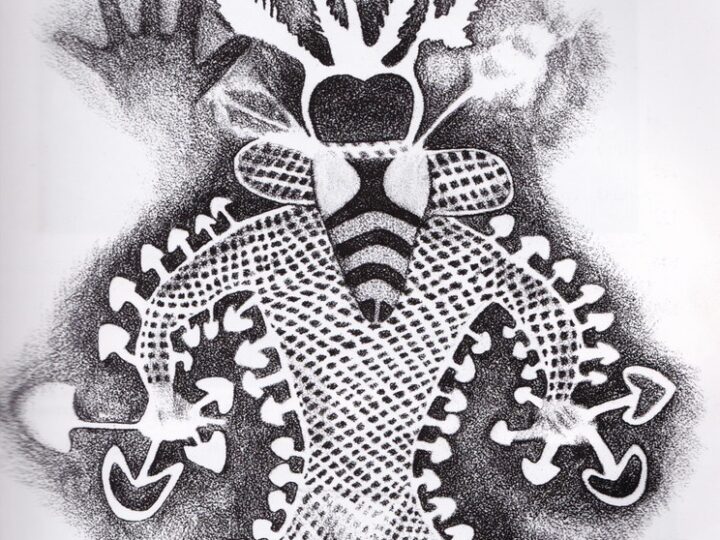

No less than the captured butterflies its photographs capture, The Butterfly Hunter is an artifact of wonder. Klea’s images have something of the clinical air of a biological study, though it is the faded wrappers themselves, rather than the much less faded butterflies themselves, that have been spread and “pinned” by the camera. Presented in chronological order, these wrappers are fragments of time and place: comic books, Arabic newspapers, bank statements, ads, and photos redolent of the complex politics of the early 70s—Kent State, nameless riots, Nixon. One of the most mysterious wrappers is an Indonesian newspaper text headed by the one word “Ada.” There is a chance it is an Indonesian review of Vladimir Nabokov’s 1969 novel, a great meditation on time. If it’s not, it might be just the sort of serendipity that Terence loved—Nabokov, who was one of his favorite authors, was a great lepidopterist as well.

For Terence McKenna fans, The Butterfly Hunter is a major treat. Along with an image of his old passport and an unpublished sketch he wrote called “The Butterfly Guru,” the book ends with a few priceless photos that Terence captioned, in third person, and sent to his mother during his time abroad. A number of the butterfly wrappers, which McKenna clearly chose for their content when he could, also speak to the esoterica that Terence would later make the meat of his word jams and writings. There are prints of Asian demons, illustrations of the human brain, and a number of papers that appear to be cut from carbon copies of his own type-written ruminations on Plotinus, Aldous Huxley, and McLuhan (“print, he is a cellular unit in a”). These represent fragments of the Joycean information theory that McKenna wrote about in his first, as yet unpublished manuscript; the fact that these thoughts are remediated here in such an artful manner would probably make the old freak say “Well, far out.”

All collections are ephemera in light of the void they attempt to keep at bay. McKenna’s other great collection—his library—was destroyed in a fire, just as Alfred Russel Wallace’s own four-year collection of Amazonian butterflies was lost when the ship transporting them back to England caught fire and sank. Klea acknowledges the transitory with images of empty wrappers and broken butterflies, but The Butterfly Hunter is still a monument of sorts to one of the more fascinating, courageous, and entertaining explorers of nature and mind in recent memory. But it is a fragile monument, as translucent as a glasswing, with all that empty light shining through.