A great book collection goes up in smoke

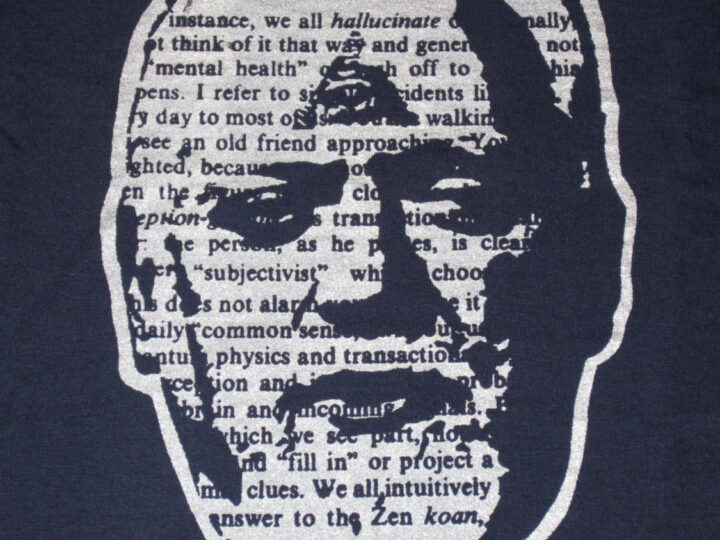

Last Wednesday, February 7, a 5-alarm blaze erupted in an old building in downtown Monterey. The fire started in a Quiznos sub shop, that exemplar of tasteful dining, and went on to thoroughly destroy a number of joints, including Goomba’s Italian restaurant, a Starbucks, and some storage offices belonging to Big Sur’s Esalen Institute—the launching point for the human potential movement. Esalen lost little of their own archives, the vast bulk of their books, photos, audio and videotapes residing elsewhere. Unfortunately, the institute was also using the offices to store the amazing library of Terence McKenna, the visionary psychedelic bard who passed away in 2000. The plan was to eventually install the books at Esalen, a place that Terence loved but which is not widely associated with scholarly pursuit. That plan will never be realized.

For those who knew Terence or enjoyed his library, the fire is a tragedy, and not simply because it consumed his private papers. Terence’s library reflected the multidimensional facets of his own mind: mysticism and history, drugs and dreams, science fiction and systems theory, natural history and art. Terence was a head who fed his head with books more than the drugs he became known for. I will never forget the sheepish look he gave me six months or so before his death, as he forked over a fistful of twenties for a copy of Empson’s Cult of the Peacock Angel, a rare book on the Yezidis that he bought from an esoteric book dealer I knew. It was a look that said, Please don’t tell my girlfriend.

Terence became a book-hound as a wee lad, and stumbled across amazing finds along his tangled way. One time, on the way to India, he came across a Theosophy library in the Seychelles that was closing its doors, and picked up its large collection of occult literature, all bound in red leather, for peanuts. The top floor of the home he built on the big island of Hawaii was designed partly to gather his thousands of volumes in one place. I visited there once towards the end of Terence’s life, to record his last formal interview. When he napped, I had the choice of poking through the library or exploring the gorgeous hideaways of Hawaii. I never left the lair.

Terence’s brother Dennis owns an index of Terence’s collection, which will at least give us an overview of his library—sorta like a playlist without the MP3s. But even this valuable document will not replace the body of knowledge itself—a body that had become, in the weird ways of the memetic world, a kind of second body for Terences fabulous and fascinating mind. No budding head will ever be able to poke through this collection again, with its faintly perfumed volumes on Chinese alchemy and butterflies and hash. And the world has one fewer 1659 folio of Isaac Casaubon’s A True and Faithful Relation of what passed between Dr. John Dee and some spirits, and one fewer old-school copy of Agrippa’s Three Books of Occult Philosophy, which Terence swapped for a pound or two of shrooms back in the day. The content of these books, at least, is reproducible; Terence, of course, was one-of-a-kind.