Esoteric Politics

Sometime around 1996, the psychedelic raconteur Terence McKenna set off to Europe with a small film crew in order to make a movie about a poignant and esoteric period of European history that the great scholar Frances Yates dubbed “the Rosicrucian Enlightenment.” The directors of the project, which did not go much beyond this initial jaunt, were Sheldon Rochlin and his wife Maxine, filmmakers and owners of Mystic Fire Video.

McKenna died in 2000 and Rochlin followed him two years later, seemingly consigning the hours of unused footage to the proverbial dustbin. But now Maxine’s son Morgan Harris, who was also on the shoot, has pieced together the fragmentary material into a reasonably cohesive work. While The Alchemical Dream falls short of the original aspirations of both McKenna and Rochlin, it is well worth a gander.

At the dawn of the 17th century, with the tension between Catholics and Protestants heating up, a small group of Protestant nobles, magicians, and reformers dedicated themselves to a vision of a new social order informed by alchemy, mysticism, and the progressive mysteries of the emerging Rosicrucian movement. Rallying around the young Frederick V, the Elector Palatine and brief “Winter King” of Bohemia, this network embraced, in McKenna’s words, “the myth of the alchemical marriage:” a moment when ideas, esoteric practices, and politics came together to change society. When this budding reformation movement was mercilessly defeated at the Battle of White Mountain in 1620, the Thirty Years War had begun, a nightmare of history from which Europe woke only to find itself utterly changed. In those bloody decades, Europe had become truly modern, with alchemy now relegated to the history of charlatanism and the metaphors of poetry.

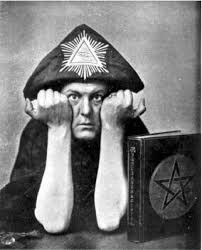

Adopting a tweedy, Alistair Cooke demeanor, McKenna tells this tale against the backdrop of his alchemical and cultural speculations, and the result is a rather satisfying romp through politics and the imagination, historical facts and occult romanticism. We hear about the visionary John Dee, the treacherous King James, and the mad Rudolph II, “the occult emperor, collector of dwarves and giants, patron of alchemy and astrology.” McKenna gives us readings from Milton, the hermetic Asclepius, and Edward Kelley’s diaries.

Though reasonably engaging, the flow of images is underwhelming, a mish mash of stock footage, static alchemical images, low-budget re-enactments a la the History Channel, and shots of Terence sitting in front of a fire or wandering around castles, though occasionally McKenna dons late Renaissance duds, including a ruff, and does the John Dee incarnation you always knew he had inside.

Towards the end of the 50-minute disc, McKenna visits an alchemical laboratory that still lurks in the bowels of the castle of Heidelburg, where Frederick briefly reigned. In a marvelous sequence, McKenna introduces us to concepts and lab equipment of alchemy (alembics, retorts, “the penguin”). In loosely Jungian terms, he characterizes the goal of alchemy as “the self that we are trying to recover…the light trapped in matter, the lux natura,…the universal medicine curing all ills, the answer. It is what everyone is looking for and no-one can find.”

Inevitably, psychedelic shamanism rears its feathered head. McKenna makes the claim that the alchemical imagination “appears to be the identical phenomenon” as the psychedelic rapture achieved through plant medicines—an intriguing but to my mind overly speculative association that depends on too many wobby assumptions and tends to sap the historical specificity of European alchemy and its own metaphors of kingship, androgyny, and transformation. Once psychedelics are mentioned, we leave the esoteric underbelly of Europe and once again enter into the now far more familiar world of jungle shamanism, which seemed a disappointing move away from a specifically European history and towards the shamanic romanticism that now dominates the New Age. That said, I was struck by McKenna’s assertion that psychedelic shamanism is a living alchemical tradition that “is not seeking the stone, but has found the stone.”

With this shamanic leap, it is clear that McKenna is on a more than historical mission with this film. At the very least, he is attempting to reframe a specific history as an overtone of the archaic past and the millennialist future. As was so often the case, McKenna seems both clear-eyed and dreamy in these speculations. He acknowledges that LSD and rock n roll were insufficient Rosicrucian triggers: “a failed alchemy instead of the dissolving and recrystalizing at a higher angelic level.” At the same time, he puts his money on the spirit of novelty and life, which he understands as an energy of dissent waged against materialism and the confines of the modern ego.

Particularly beautiful is his understanding of the alchemical gold as neither a material mineral or a merely psychological product, but as meaning itself, a reflection of the recognition that “meaning lies in the confrontation of contradiction, the coincidentia oppositorum, the rediscovery of the real ambiguity of being.” Though The Alchemical Dream does not escape its own less productive ambiguities, it still offers up a glimpse or two of that imaginal garden through the keyhole of historical time.