I am currently recovering from three very full days of the Chacruna Institute’s Religion and Psychedelics Forum. The event went amazingly well, with a high level of discourse from both panelists and chatting attendees, a diverse and ecumenical array of views unmarred by haters and trolls, and a lovely fusion of head and heart rare to find in such an abstract, draining thing as an online conference. I moderated a bunch of panels, interviewed Brian Muraresku, and, since I was involved with a lot of the programming, watched pretty much everything. When we make the recordings available, I will try and write more about the conference, but I do believe the Religion and Psychedelics Forum will stand as one of those rare Zoom (actually, Crowdcast) conferences that are worth returning to after the fact.

The timing was also perfect: psychedelics and religion is fresh and resonant right now, partly because the topic sidesteps the medicalizing and commercial rhetoric that has made the psychedelic scene both boring and aggravating. Obviously religion can be a huge problem, and future conversations will no doubt have plenty of challenges to wrestle with. But with psychedelic chaplaincy just starting to bloom, we are in a sweet spot, at once calming and intoxicating. The Forum reminded me just how wild, enchanted, and disruptive the psychedelic waters become when neuropsychology can open to phenomenology and mystery. Plus it was just wonderfully weird hearing mainline liberal Christians from the American South lovingly describing their trips.

As tools and teachers of the Beyond and the Outside (as well as the Here and Now), psychedelics inevitably open up the problem and power of the sacred, whether researchers are defining “mystical experience” or the daime drinkers of Barquinha are incorporating spirits of the dead or religious professionals, noting which way the wind is blowing, are moving into the psychedelic space as chaplains, guides, and ritual participants. I guarantee you will not see this groundswell reflected much in the next MAPS Psychedelic Science conference. In this sense, religion—rather than “spirituality,” which is far more easily absorbed into secular psychology, pop hedonism, and consumer wellness marketing plans—is the elephant in the psychedelic renaissance room.

But I want to talk about another elephant in that room: the elephant LSD-25. And I am not talking about poor Tusko, the Oklahoma pachyderm who was killed in 1962 after being injected with almost 300 milligrams of LSD by university researchers. What I am talking about is the fact that LSD’s cultural profile is curiously muted in today’s “psychedelic space”, though acid remains without question the single most influential and catalyzing psychedelic in the postwar world. Within the mediated mindscape of the day, acid is there, but not there, acknowledged but not exactly honored as the teacher and trickster and transformer it is.

Many of the more-or-less religious substances discussed at the conference were linked to sacred plants and fungi and the indigenous and mestizo peoples and religions that nurture that botanical knowledge. (Chacruna itself is named after the leaves in the ayahuasca brew). There was some discussion of ketamine, and LSD was mentioned on occasion, but its presence was most strongly felt in a panel I organized called “The Psychedelic Religion of the Counterculture.” This panel, which included Christian Greer talking about the psychedelic church movement of the ‘60s, Hog Farmer Maria Mangini on the rituals of acid (and nitrous oxide) communitas, and the amazing Nick Powers on Burning Man’s profane spirituality, was a good reminder that, in WEIRD societies—Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic—acid is at least as much of an ally or lineage or sacramental pact as anything else.

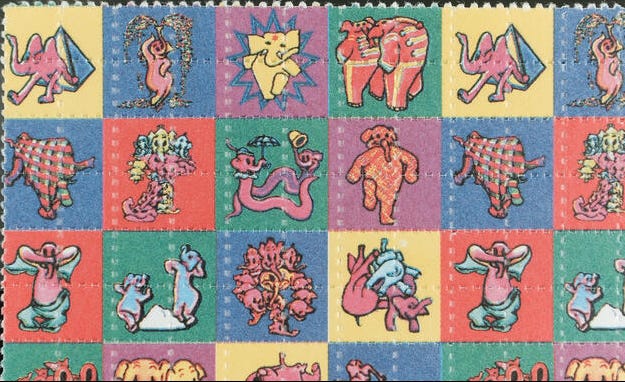

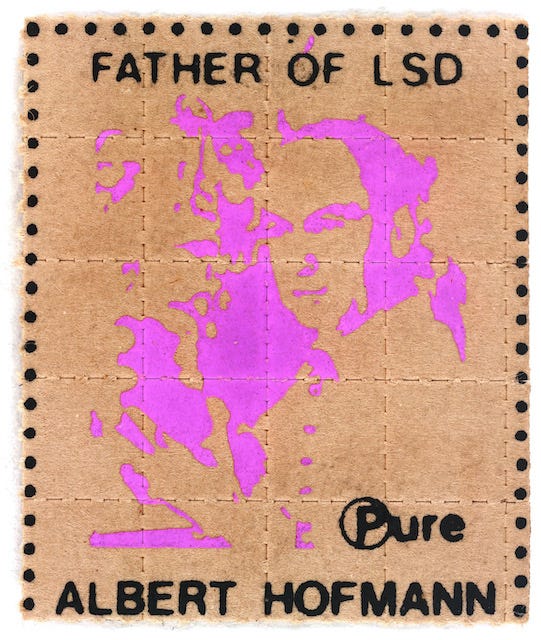

I am a child of this lineage. I first dropped a modestly dosed disco hit at the tender age of 13, on Halloween, and its signature qualities—limpid, electric, loopy, sublime—remain my entheogenic home base. The drug has also been on my mind a lot of late, since I have spent the last two years researching and writing about something that is now exceptionally rare, a largely undiscussed facet of the acid story. As Burning Shore readers already know, my latest book project takes on the history, art, and design of LSD blotter, a carrier medium almost uniquely associated with LSD and responsible for the bulk of the drug’s street distribution from the end of the 1970s to today.

In a way we know the story of acid, which can seem superficially settled, even rote, its signature events and colorful characters trotted out like clockwork in myriad online potted histories: Dr. Hofmann’s bike ride, MK-Ultra’s miseries, Michael Hollingshead’s mayo jar, Kesey’s Kool-Aid, Manson’s mind control, Jerry’s bone-dancing congregation. I largely ignored these stories along with discussions of acid ideology, except to the extent that it helps explain the motivation of blotter makers. What interested me were the elusive nitty-gritty details of manufacturing practices, drug distribution, and the fascinating and mixed motivations of the artists, producers, printmakers, and dealers who developed the blotter format into a unique mode of art—or iconography, or branding—whose images reflect all manner of aesthetic, cultural, spiritual, and prankster attitudes. Following a space opened up by Jesse Jarnow’s book Heads, my research put me in touch with the concrete social reality of the acid underground, which persisted whether or not the drug was in the papers, underground or otherwise. After all, given that blotter only really takes off in the late 1970s, its story lies mostly outside the conventional ‘60s narratives of LSD.

But if LSD never stopped influencing culture, and if the drug remains a popular goodie—dependably available in underground drug markets, at festivals, and on drug-nerd dark webs—why do I call LSD the elephant in the room? Here’s why. If you tune into the journals and journalism of today, along with the imaginative investments that inform much of psychedelic discourse, you will note that LSD has taken a back seat in academic research, therapeutic protocols, and the cultural imaginary. In an era of “sacred plants,” of commercial formulations and utterly manageable microdosing, LSD the Mighty has drifted to the periphery of our consciousness, its teachings discursively marginalized, almost repressed, even as its tropes are regurgitated as Haight Street kitsch and corny vanity blotter. We forget that the elephant in the room can roar like a cosmic hurricane. But if you climb on its back, and embrace the positionality of the acidhead, you are gifted with a particularly illuminating perspective on the current psychedelic scene, for the simple fact that, beyond the cliches that imprison, LSD is not currently subjected to capitalist narrative capture.

Let’s back up for a sec. A lot of psychedelic discourse today is driven by an overt or covert struggle over legitimacy. Who gets to speak for psychedelics, and in what tongue? This struggle is partly an institutional one, which is why it feels so real. In the domain of mental health, professional bodies—including credentialed therapists and the institutions that license them—are now directly competing with already existing underground therapy networks whose days may well be numbered already. Recent debates about governance and abuse within underground therapy networks, however vital and deserved, must also be seen in light of this larger movement towards professionalization.

This therapeutic land rush is in turn dependent on the “return” of psychedelic science and clinical research. Here too we have seen various professional bodies and discourses, with rivalries between them, attempt to establish their dominance over the knowledge basis of psychedelics, partly with an eye to extract value for a hungry pharmaceutical and mental health industry. One example of this tension is a topic that frequently came up at the Chacruna Forum: what is “mystical experience,” and is it really translatable to data, as the popular Mystical Experience Questionnaire implies? The labs at Johns Hopkins and NYU dig this stuff, but other psychedelic scientists—for some very good reasons—think these measures open the door to supernatural obscurantism.

Or you can consider the rivalry that motivates the self-serving claim, which I’ve seen put forward by white-coats at various psychedelic science gatherings, that psychedelic science stopped with the scheduling of LSD and related compounds in the ‘60s and early ‘70s, and only started up again with the renaissance man Roland Griffiths or, if they are being fair, Rick Strassman. But this narrative only stands if you believe that “real” science can’t happen outside of legitimizing institutions. If you do believe this, please explain where we should locate Sasha Shulgin, or Jonathan Ott, or the garage botanists who haunted the great Entheogen Review.

So here’s what you see from on top of the elephant. Professional therapists, along with clinical researchers and psychedelic entrepreneurs, have very strong reasons, both financial and optical, to marginalize or actively forget seventy-five years of LSD history, culture, and consciousness. Part of this is simply practical. From a working therapist’s point of view, LSD doesn’t make sense because it takes too long to metabolize, which stretches a session into hours and hours of sticky trip taffy that increases the likelihood of weird twists and turns and just takes a lot of time. Underground therapists have an extraordinary history of working with LSD, of course, but these were and are not “mass” protocols designed to profitably treat society-wide mental turmoil. Almost no one interested in installing a mainstream regimen of psychedelic therapy is paying much attention to LSD, despite the distinct possibility that the substance remains a uniquely excellent vehicle for the autonomous deconstruction and lucid reformation of self-patterns. But no matter: LSD doesn’t “scale.”

But what about pure research? Because LSD has been so widely studied, the material is very well-known and continues to play an important role in some current psychedelic science, including animal studies. Significant research by Robin Carhart-Harris and Franz Vollenweider has been carried out using LSD as the primary material (although some of this interest may be traced to acidhead favoritism in a few funding agencies). Still, that metabolic arc makes human trials an expensive hassle and a half. Psilocybin is a much better clinical ally.

There are also powerful political reasons that drive contemporary clinical researchers—and their pharmacorp and entrepreneurial pals—to downplay LSD: the desire to enforce a new narrative freed from the dastardly taint of the counterculture. While mescaline, psilocybin, DMT, and ketamine all added their alkaloids to the countercultural ferment, LSD remains the great psychedelic starter. By downplaying LSD and disconnecting its histories from the contemporary construct of “psychedelics”, the legacy of the counterculture can be jettisoned as an ancient and unfortunate tale of dangerous excess no longer relevant to today’s era of bright and shining promise. This marginalization also conveniently mutes the more radical discourses, practices, and collective politics associated with LSD, whether revolutionary communes, or prophetic religious invention, or hedonistic erotic celebration.

The bête noire for many researchers is Timothy Leary, who gets blamed for destroying the first wave of psychedelic science by supporting, and intensely publicizing, the democratic distribution of psychedelics and LSD in particular to the wider population. (It’s interesting to note that Leary gets grief while the university-based drug torturers who got paid by MK-Ultra barely get a mention.) I have also always suspected that part of the opprobrium that comes Leary’s way reflects the fact that, in addition to being a photogenic pied piper, he was a professional turncoat, an awkward reminder that psychedelic researchers have the capacity to pursue values that are incommensurate with those that drive the modern research university.

Alongside these institutional forms of forgetting, there has also been a broad shift in the cultural imaginary, which finds far more enchantment and promise in organic psychedelics like ayahuasca and psilocybin mushrooms, along with ibogaine and mescaline-containing cacti. Part of this shift is generational—I get the sense that for some younger folk, LSD is as antiquated (if excellent) as a reel-to-reel, its legends and trip reports worthy of little more than an “OK boomer.” Another part has to do with the impressive success of local decriminalization efforts that focus, for practical reasons, on “plant medicines” and the rhetoric of Nature. The supposed tension between natural and synthetic drugs is an old debate in the underground, often generating more heat than light, but the fact is that Nature gives plant medicines and fungi an enchanting animism lacking in LSD. (Though it bears mentioning that ayahuasca is also a thing of techne.) Journeyers readily experience and attribute agency to natural substances, which feeds directly into the widespread dread of climate crisis and imminent environmental catastrophe. One often hears the tale that ayahuasca left the jungle to spread around the globe in order to wake up humanity before we totally fuck things up.

Along with this ecological/animist bias lies a corresponding ethnobotanical romance. Ayahuasca, teonanácatl, iboga, huachuma, and peyote are all profoundly embedded, historically and cosmically, in indigenous frameworks of use and lore. Many Western individuals—reeling from an extractivist civilization they feel terribly ashamed to benefit from—are understandably hungry to acknowledge, celebrate, and center these indigenous forms of wisdom. Their motives—my motives as well—include ethical demands based on historical horror, along with a genuine respect and interest in indigenous worldviews, and probably, if we are honest, some good ole romantic enchantment with the Other. The point is that the indigenous lineages that have held and developed the practice of sacred plants and fungi for millennia charge these particular substances with a far more potent charisma than currently radiates from lysergic acid diethylamide-25, a semi-synthetic molecule the sprung like Athena from the corporate brow of the European chemical industry.

But what a new god! LSD is the Holy Spirit of the postwar world, its arrival a pentecost for the profane, a Mystery that compounds madness, mysticism, mind control, and revolutionary ontology. LSD holds up a funhouse mirror to the WEIRD world, generating all manner of masks, terrifying and absurd and absolutely revelatory. Consider that, within a few decades of its discovery, LSD would be seen not only as a simulator of psychosis—the original “psychoto-mimetic” marketed by Sandoz—but as a facilitator of psychoanalytic insight, a battlefield deliriant, a cure for alcoholism, a truth serum, a liberating agent of revolution, a repressive tool of counter-revolution, an aphrodisiac, a cognitive amplifier, a creativity booster, a holy sacrament, a profane sacrament, and a compound with no “currently accepted medical use” and “a high potential for abuse” (the definitions of Schedule I substances in the United States). LSD is a Proteus, a trickster, a psychopomp of modernity. Nonetheless, Dame Acid is largely obscured when seen through today’s psychedelic kaleidoscope. It is too close, too far-out, its sacred transmissions too muddled with the scandalous grit of its concrete historical unfoldment.

Here I would like to suggest that this bug, this uncoolness, is actually a feature. Why? Because, for both practical and symbolic reasons, LSD has been largely passed over by the discursive, legal, entrepreneurial, therapeutic, and marketing engines that are utterly transforming the narrative profile that surrounds, say, psilocybin mushrooms (already frequently reduced to “psilocybin”). I cannot speak for those acid users who exist among indigenous communities and the developing world (and they are there). But for WEIRDOs, the absence of contemporary acid hype means there is still some room to breathe with LSD, to encounter the Mystery on terms dictated by generations of the drug’s users more than by crypto-capitalists, drug-naive enthusiasts, and Goopy marketers. Though acid has done many of us wonders, this white lab powder is paradoxically too “wild” to be captured whole-hog by the narrative template of Healing, with its medicalized subjects, pharmaceutical regimens, and wellness indulgences.

As a material substance, LSD is also largely untouched by the legacy of colonialism—at least to the extent that anything born in Europe can be untouched by colonialism. Acid is certainly not “clean” (though it’s nice when it is). Karmically, LSD emerges directly from the West’s industrial pact with fossil fuels—like other chemical combines, Sandoz was born when we clever monkeys figured out how to extract dyes from coal-tar wastes. (Cue Gravity’s Rainbow.) And the popular youth culture that later grew up around acid indulged in an extraordinary amount of appropriation, both in the “good” sense of creative cultural cannibalism and the “bad” sense of thoughtless Western thievery. But unlike shrooms or ayahuasca or Salvia divinorum, acid itself cannot be constructed as an object of cultural appropriation.

What a relief! Acid provides culturally sensitive WEIRDOS room to celebrate without guilt or risk of attack, without the demand to negotiate the appropriateness of their own relationship to a substance. And because of the postwar order, this accessibility not only holds for Westerners, but for everyone, since acid follows other global flows of trade and travel. But the particular Western alliance with LSD also demands its own forms of responsibility and reciprocity, forms that Westerners aren’t usually very good at, unlike a lot of indigenous folks. For while LSD lacks anything like a “traditional” framework of ritual or symbolic meaning, it carries with it a rich and varied load of therapeutic, bohemian, and cultural practices, an appropriately kaleidoscopic range of collective ceremonies, aesthetic gestures, mythopoetic maps, wayward tantras, and metaphysical insights. Most of this lore belongs to the underground, or really a network of undergrounds, and while a good deal of it lies in texts—including the “texts” of LPs and rock posters and underground comix—a lot lies with folks or scenes that have disappeared, are disappearing, or molder in the basements of cultural memory.

One reason I brought together some friends to discuss “The Psychedelic Religion of the Counterculture” was to see how our understanding of the counterculture shifted when we looked at it as a religious movement rather than simply a spiritual one. But a more pressing reason was to draw attention to the fact that, at a time when many young psychedelic seekers are yearning for shamanic wisdom, the West’s own bohemian ancestors are aging and dying all around us. Just as a rising tide of voices, including my own, demand a place for indigenous folks and organizations at the psychedelic table, so too might we more consciously acknowledge, affirm, and empower our own often marginalized psychedelic elders, that Trippiest Generation of freaks, heads, and freelance mystics now reaching the end of the road. For a glimpse of what I am talking about, check out Christopher Gray’s criminally unknown and phenomenally inspiring 2010 book The Acid Diaries, a record of the boomer seeker’s late return to LSD.

For all their fuck-ups, the chaotic underground lineage of the psychedelic counterculture may paradoxically hold the sort of “traditional values” that could help guide us through the ferocious new psychedelic frontier, where the digital railway networks unload a fresh swarm of carpetbaggers, snake-oil salesmen, and robber barons to be on a daily basis. If we want to prepare ourselves for the massive bloom of psychedelic experiences that lies ahead—which, let us not fool ourselves, is going to get seriously out of hand—why would we ignore the first wave of mind-expanding mass democracy in the West? If the sacred is what we are after, why ignore the blotter host? If celebration, why not join the Mad Hatter in a sillier sort of tea ceremony? And if you want to get to the heart of the Mystery, don’t you think you might wanna follow that white Pooka down that long strange rabbit hole?

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar.

Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so please pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!