A profile of Lovecraft’s life and work

In this book it is spoken of…Spirits and Conjurations; of Gods, Spheres, Planes and many other things which may or may not exist. It is immaterial whether they exist or not. By doing certain things certain results follow.

—Aleister Crowley

Consumed by cancer in 1937 at the age of 46, the last scion of a faded aristocratic New England family, the horror writer Howard Phillips Lovecraft left one of America’s most curious literary legacies. The bulk of his short stories appeared in Weird Tales, a pulp magazine devoted to the supernatural. But within these modest confines, Lovecraft brought dark fantasy screaming into the 20th century, taking the genre, almost literally, into a new dimension.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the loosely linked cycle of stories known as the Cthulhu Mythos. Named for a tentacled alien monster who waits dreaming beneath the sea in the sunken city of R’lyeh, the Mythos encompasses the cosmic career of a variety of gruesome extraterrestrial entities that include Yog-Sothoth, Nyarlathotep, and the blind idiot god Azathoth, who sprawls at the center of Ultimate Chaos, “encircled by his flopping horde of mindless and amorphous dancers, and lulled by the thin monotonous piping of a demonic flute held in nameless paws.”[1] Lurking on the margins of our space-time continuum, this merry crew of Outer Gods and Great Old Ones are now attempting to invade our world through science and dream and horrid rites.

As a marginally popular writer working in the literary equivalent of the gutter, Lovecraft received no serious attention during his lifetime. But while most 1930s pulp fiction is nearly unreadable today, Lovecraft continues to attract attention. In France and Japan, his tales of cosmic fungi, degenerate cults and seriously bad dreams are recognized as works of bent genius, and the celebrated French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari praise his radical embrace of multiplicity in their magnum opus A Thousand Plateaus.[2] On Anglo-American turf, a passionate cabal of critics fill journals like Lovecraft Studies and Crypt of Cthulhu with their almost talmudic research. Meanwhile both hacks and gifted disciples continue to craft stories that elaborate the Cthulhu Mythos. There’s even a Lovecraft convention—the NecronomiCon, named for the most famous of his forbidden grimoires. Like the gnostic science fiction writer Philip K. Dick, H.P. Lovecraft is the epitome of a cult author.

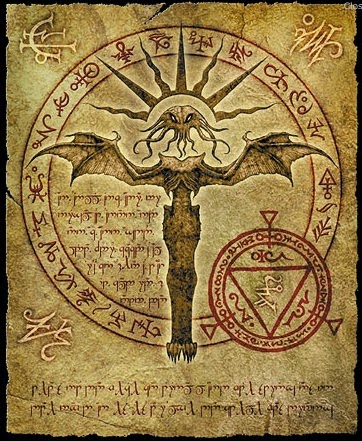

The word “fan” comes from fanaticus, an ancient term for a temple devotee, and Lovecraft fans exhibit the unflagging devotion, fetishism and sectarian debates that have characterized popular religious cults throughout the ages. But Lovecraft’s “cult” status has a curiously literal dimension. Many magicians and occultists have taken up his Mythos as source material for their practice. Drawn from the darker regions of the esoteric counterculture—Thelema and Satanism and Chaos magic—these Lovecraftian mages actively seek to generate the terrifying and atavistic encounters that Lovecraft’s protagonists stumble into compulsively, blindly or against their will.

Secondary occult sources for Lovecraftian magic include three different “fake” editions of the Necronomicon, a few rites included in Anton LaVey’s The Satanic Rituals, and a number of works by the loopy British Thelemite Kenneth Grant. Besides Grant’s Typhonian O.T.O. and the Temple of Set’s Order of the Trapezoid, magical sects that tap the Cthulhu current have included the Esoteric Order of Dagon, the Bate Cabal, Michael Bertiaux’s Lovecraftian Coven, and a Starry Wisdom group in Florida, named after the nineteenth-century sect featured in Lovecraft’s “Haunter of the Dark.” Solo chaos mages fill out the ranks, cobbling together Lovecraftian arcana on the Internet or freely sampling the Mythos in their chthonic, open-ended (anti-) workings.

This phenomenon is made all the more intriguing by the fact that Lovecraft himself was a “mechanistic materialist” philosophically opposed to spirituality and magic of any kind. Accounting for this discrepancy is only one of many curious problems raised by the apparent power of Lovecraftian magic. Why and how do these pulp visions “work”? What constitutes the “authentic” occult? How does magic relate to the tension between fact and fable? As I hope to show, Lovecraftian magic is not a pop hallucination but an imaginative and coherent “reading” set in motion by the dynamics of Lovecraft’s own texts, a set of thematic, stylistic, and intertextual strategies which constitute what I call Lovecraft’s Magick Realism.

Magical realism already denotes a strain of Latin American fiction—exemplified by Borges, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and Isabel Allende—in which a fantastic dreamlike logic melds seamlessly and delightfully with the rhythms of the everyday. Lovecraft’s Magick Realism is far more dark and convulsive, as ancient and amoral forces violently puncture the realistic surface of his tales. Lovecraft constructs and then collapses a number of intense polarities—between realism and fantasy, book and dream, reason and its chaotic Other. By playing out these tensions in his writing, Lovecraft also reflects the transformations that darkside occultism has undergone as it confronts modernity in such forms as psychology, quantum physics, and the existential groundlessness of being. And by embedding all this in an intertextual Mythos of profound depth, he draws the reader into the chaos that lies “between the worlds” of magick and reality.

A Pulp Poe

Written mostly in the 1920s and ’30s, Lovecraft’s work builds a somewhat rickety bridge between the florid decadence of fin de siecle fantasy and the more “rational” demands of the new century’s science fiction. His early writing is gaudy Gothic pastiche, but in his mature Cthulhu tales, Lovecraft adopts a pseudodocumentary style that utilizes the language of journalism, scholarship, and science to construct a realistic and measured prose voice which then explodes into feverish, adjectival horror. Some find Lovecraft’s intensity atrocious—not everyone can enjoy a writer capable of comparing a strange light to “a glutted swarm of corpse-fed fireflies dancing hellish sarabands over an accursed marsh.”[3]

But in terms of horror, Lovecraft delivers. His protagonist is usually a reclusive bookish type, a scholar or artist who is or is known to the first-person narrator. Stumbling onto odd coincidences or beset with strange dreams, his intellectual curiosity drives him to pore through forbidden books or local folklore, his empirical turn of mind blinding him to the nightmarish scenario that the reader can see slowly building up around him. When the Mythos finally breaks through, it often shatters him, even though the invasion is generally more cognitive than physical.

By endlessly playing out a shared collection of images and tropes, genres like weird fiction also generate a collective resonance that can seem both “archetypal” and cliched. Though Lovecraft broke with classic fantasy, he gave his Mythos density and depth by building a shared world to house his disparate tales. The Mythos stories all share a liminal map that weaves fictional places like Arkham, Dunwich, and Miskatonic University into the New England landscape; they also refer to a common body of entities and forbidden books. A relatively common feature in fantasy fiction, these metafictional techniques create the sense that Lovecraft’s Mythos lies beyond each individual tales, hovering in a dimension halfway between fantasy and the real.

Lovecraft did not just tell tales—he built a world. It’s no accident that one of the more successful role-playing games to follow in the heels of Dungeons & Dragons takes place in “Lovecraft Country.” Most role-playing adventure games build their worlds inside highly codified “mythic” spaces of the collective imagination (heroic fantasy, cyberpunk, vampire Paris, Arthur’s Britain). The game Call of Cthulhu takes place in Lovecraft’s 1920s America, where players become “investigators” who track down dark rumors or heinous occult crimes that gradually open up the reality of the monsters. Call of Cthulhu is an unusually dark game; the best investigators can do is to retain sanity and stave off the monsters’ eventual apocalyptic triumph. In many ways Call of Cthulhu “works” because of the considerable density of Lovecraft’s original Mythos, a density which the game itself also contributes to.

Lovecraft himself “collectivized” and deepened his Mythos by encouraging his friends to write stories that take place within it. Writers like Clark Ashton Smith, Robert Howard, and a young Robert Bloch complied. After Lovecraft’s death, August Derleth carried on this tradition with great devotion, and today, dozens continue to write Lovecraftian tales.

With some notable exceptions, most of these writers mangle the Myth, often by detailing horrors the master wisely left shrouded in ambiguous gloom.[4] The exact delineations of Lovecraft’s cosmic cast and timeline remain murky even after a great deal of close-reading and cross-referencing. But in the hands of the Catholic Derleth, the extraterrestrial Great Old Ones become elemental demons defeated by the “good” Elder Gods. Forcing Lovecraft’s cosmic and fundamentally amoral pantheon into a traditional religious framework, Derleth committed an error at once imaginative and interpretive. For despite the diabolical aura of his creatures, Lovecraft generates much of his power by stepping beyond good and evil.

The Horror of Reason

For the most part Lovecraft abandoned the supernatural and religious underpinnings of the classic supernatural tale, turning instead looked towards science to provide frameworks for horror. Calling Lovecraft the “Copernicus of the horror tale,” the fantasy writer Fritz Leiber Jr. wrote that Lovecraft was the first fantasist who “firmly attached the emotion of spectral dread to such concepts as outer space, the rim of the cosmos, alien beings, unsuspected dimensions, and the conceivable universes lying outside our own spacetime continuum.”[5] As Lovecraft himself put it in a letter, “The time has come when the normal revolt against time, space, and matter must assume a form not overtly incompatible with what is known of reality—when it must be gratified by images forming supplements rather than contradictions of the visible and measurable universe.”[6]

For Lovecraft, it is not the sleep of reason that breeds monsters, but reason with its eyes agog. By fusing cutting-edge science with archaic material, Lovecraft creates a twisted materialism in which scientific “progress” returns us to the atavistic abyss, and hard-nosed research revives the factual basis of forgotten and discarded myths. Hence Lovecraft’s obsession with archeology; the digs which unearth alien artifacts and bizarrely angled cities are simultaneously historical and imaginal. In 1930 story “The Whisperer in Darkness,” Lovecraft identifies the planet Yuggoth (from which the fungoid Mi-Go launch their clandestine invasions of Earth) with the newly-discovered planet called Pluto. To the 1930 reader—probably the kind of person who would thrill to popular accounts of C.W. Thompson’s discovery of the ninth planet that very year—this factual reference “opens up” Lovecraft’s fiction into a real world that is itself opening up to the limitless cosmos.

Lovecraft’s most self-conscious, if somewhat strained, fusion of occult folklore and weird science occurs in the 1932 story “The Dreams of the Witch-House.” The demonic characters that the folklorist Walter Gilman first glimpses in his nightmares are stock ghoulies: the evil witch crone Keziah Mason, her familiar spirit Brown Jenkin, and a “Black Man” who is perhaps Lovecraft’s most unambiguously Satanic figure. These figures eventually invade the real space of Gilman’s curiously angled room. But Gilman is also a student of quantum physics, Riemann spaces and non-Euclidian mathematics, and his dreams are almost psychedelic manifestations of his abstract knowledge. Within these “abysses whose material and gravitational properties…he could not even begin to explain,” an “indescribably angled” realm of “titan prisms, labyrinths, cube-and-plane clusters and quasi-buildings,” Gilman keeps encountering a small polyhedron and a mass of “prolately spheroidal bubbles.” By the end of the tale that he realizes that these are none other than Keziah and her familiar spirit, classic demonic cliches translated into the most alien dimension of speculative science: hyperspace.

These days, one finds the motif of hyperspace in science fiction, pop cosmology, computer interface design, channelled UFO prophecies, and the postmodern shamanism of today’s high-octane psychedelic travellers—all discourses that feed contemporary chaos magic. The term itself was probably coined by the science fiction writer John W. Campbell Jr.in 1931, though its origins as a concept lie in nineteenth-century mathematical explorations of the fourth dimension.

In many ways, however, Lovecraft was the concept’s first mythographer. From the perspective of hyperspace, our normal, three-dimensional spaces are exhausted and insufficient constructs. But our incapacity to vividly imagine this new dimension in humanist terms creates a crisis of representation, a crisis which for Lovecraft calls up our most ancient fears of the unknown. “All the objects…were totally beyond description or even comprehension,” Lovecraft writes of Gilman’s seething nightmare before paradoxically proceeding to describe these horrible objects. In his descriptions, Lovecraft emphasizes the incommensurability of this space through almost non-sensical juxtapositions like “obscene angles” or “wrong” geometry, a rhetorical technique that one Chaos magician calls “Semiotic Angularity.”

Lovecraft has a habit of labeling his horrors “indescribable,” “nameless, “unseen,” “unutterable,” “unknown” and “formless.” Though superficially weak, this move can also be seen a kind of macabre via negativa. Like the apophatic oppositions of negative theologians like Pseudo-Dionysus or St. John of the Cross, Lovecraft marks the limits of language, limits which paradoxically point to the Beyond. For the mystics, this ultimate is the ineffable One, Pseudo-Dionysus’ “superluminous gloom” or the Ain Soph of the Kabbalists. But there is no unity in Lovecraft’s Beyond. It is the omnivorous Outside, the screaming multiplicity of cosmic hyperspace opened up by reason.

For Lovecraft, scientific materialism is the ultimate Faustian bargain, not because it hands us Promethean technology (a man for the eighteenth century, Lovecraft had no interest in gadgetry), but because it leads us beyond the horizon of what our minds can withstand. “The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the mind to correlate all its contents,” goes the famous opening line of “Call of Cthulhu.” By correlating those contexts, empiricism opens up “terrifying vistas of reality”—what Lovecraft elsewhere calls “the blind cosmos [that] grinds aimlessly on from nothing to something and from something back to nothing again, neither heeding nor knowing the wishes or existence of the minds that flicker for a second now and then in the darkness”.

Lovecraft gave this existentialist dread an imaginative voice, what he called “cosmic alienage”. For Fritz Leiber, the “monstrous nuclear chaos” of Azathoth, Lovecraft’s supreme entity, symbolizes “the purposeless, mindless, yet all-powerful universe of materialistic belief.” But this symbolism isn’t the whole story, for, as DMT voyagers know, hyperspace is haunted. The entities that erupt from Lovecraft’s inhuman realms seem to suggest that in a blind mechanistic cosmos, the most alien thing is sentience itself. Peering outward through the cracks of domesticated “human” consciousness, a compassionless materialist like Lovecraft could only react with horror, for reason must cower before the most raw and atavistic dream-dragons of the psyche.

Modern humans usually suppress, ignore or constrain these forces lurking in our lizard brain. Mythically, these forces take the form of demons imprisoned under the angelic yokes of altruism, morality, and intellect. Yet if one does not believe in any ultimate universal purpose, then these primal forces are the most attuned with the cosmos precisely because they are amoral and inhuman. In “The Dunwich Horror”, Henry Wheeler overhears a monstrous moan from a diabolical rite and asks “from what unplumbed gulfs of extra-cosmic consciousness or obscure, long-latent heredity, were those half-articular thunder-croakings drawn?” The Outside is within.

Chaos Culture and Calling Cthulhu

Lovecraft’s fiction expresses a “future primitivism” that finds its most intense esoteric expression in Chaos magic, an eclectic contemporary style of darkside occultism that draws from Thelema, Satanism, Austin Osman Spare, and Eastern metaphysics to construct a thoroughly postmodern magic.

For today’s Chaos mages, there is no “tradition”. The symbols and myths of countless sects, orders, and faiths, are constructs, useful fictions, “games.” That magic works has nothing to do with its truth claims and everything to do with the will and experience of the magician. Recognizing the distinct possibility that we may be adrift in a meaningless mechanical cosmos within which human will and imagination are vaguely comic flukes (the “cosmic indifferentism” Lovecraft himself professed), the mage accepts his groundlessness, embracing the chaotic self-creating void that is himself.

As we find with Lovecraft’s fictional cults and grimoires, chaos magicians refuse the hierarchical, symbolic and monotheist biases of traditional esotericism. Like most Chaos magicians, the British occultist Peter Carroll gravitates towards the Black, not because he desires a simple Satanic inversion of Christianity but becuase he seeks the amoral and shamanic core of magical experience—a core that Lovecraft conjures up with his orgies of drums, guttural chants, and screeching horns. At the same time, Chaos mages like Carroll also plumb the weird science of quantum physics, complexity theory and electronic Prometheanism. Some darkside magicians become consumed by the atavistic forces they unleash or addicted to the dark costume of the Satanic anti-hero. But the most sophisticated adopt a balanced mode of gnostic existentialism that calls all constructs into question while refusing the cold comforts of skeptical reason or suicidal nihilism, a pragmatic and empirical shamanism that resonates as much with Lovecraft’s hard-headed materialism as with his horrors.

The first occultist to really engage these notions is Aleister Crowley, who shattered the received vessels of occult tradition while creatively extending the dark dream of magic into the twentieth century. With his outlandish image, trickster texts, and his famous Law of Thelema (“Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law”), Crowley called into question the esoteric certainties of “true” revelation and lineage, and was the first magus to give occult antinomionism a decidedly Nietzschean twist.[7]

Unfettered, this occult will to power can easily degenerate into a heartless elitism, and the fascist and racist dimensions of both twentieth-century occultism and Lovecraft himself should not be forgotten. But this self-engendering will is more exuberantly expressed as a will to Art. In many ways, the fin de siecle occultism that exploded during Crowley’s time was an essentially esthetic esotericism. A good number of the nineteenth-century magicians who inspire us today are the great poets, painters, and writers of Symbolism and decadent Romanticism, many of them dabblers or adepts in Satanism, Rosicrucianism, and hermetic societies. The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn was infused with artistic pretensions, and Golden Dawn member and fantasy writer Arthur Machen was one of Lovecraft’s strongest influences.

But it was Austin Osman Spare who most decisively dissolved the boundary between artistic and magical life. Though working independently of the Surrealists, Spare also based his art on the dark and autonomous eruptions of “subconscious” material, though in a more overtly theurgic context.[8] Today’s Chaos magicians are heavily influenced by Spare, and their Lovecraftian rites express this simultaneously creative and nihilistic dissolution. And as postmodern spawn of role-playing games, computers, and pop culture, they celebrate the fact that Lovecraft’s secrets are scraped from the barrel of pulp fiction.

Proof in the Pudding

In a message cross-posted to the Internet newsgroups alt.necromicon [sic] and alt.satanism, Parker Ryan listed a wide variety of magical techniques described by Lovecraft, including entheogens, glossalalia, and shamanic drumming. Insisting that his post was “not a satirical article,” Ryan then described specific Lovecraftian rites he had developed, including this “Rite of Cthulhu”:

A) Chanting. The use of the “Cthulhu chant” to create a concentrative or meditative state of consciousness that forms the basis of much later magickal work.

B) Dream work. Specific techniques of controlled dreaming that are used to establish contact with Cthulhu.

C) Abandonment. Specific techniques to free oneself from culturally conditioned reality tunnels.

Ryan goes on to say that he’s experimented with most of his rites “with fairly good success.”

In coming to terms with the “real magic” embedded in Lovecraft, one quickly encounters a fundamental irony: the cold skepticism of Lovecraft himself. In his letters, Lovecraft poked fun at his own tales, claiming he wrote them for cash and playfully naming his friends after his monsters. While such attitudes in no way diminish the imaginative power of Lovecraft’s tales—which, as always, lie outside the control and intention of their author—they do pose a problem for the working occultist seeking to establish Lovecraft’s magical authority.

The most obvious, and least interesting, answer is to find authentic magic in Lovecraft’s biography. Lovecraft’s father was a traveling salesman who died in a madhouse when Lovecraft was eight, and vague rumors that he was an initiate in some Masonic order or other were exploited in the Necronomicon cobbled together by George Hay, Colin Wilson, and Robert Turner. Others have tried to track Lovecraft’s occult know-how, especially his familiarity with Aleister Crowley and the Golden Dawn. In an Internet document relating the history of the “real” Necronomicon, Colin Low argues that Crowley befriended Sonia Greene in New York a few years before the woman married Lovecraft. As proof of Crowley’s indirect influence on Lovecraft, Low sites this intriguing passage from “The Call of Cthulhu”:

That cult would never die until the stars came right again and the secret priests would take Cthulhu from His tomb to revive His subjects and resume His rule of earth. The time would be easy to know, for then mankind would have become as the Great Old Ones; free and wild, and beyond good and evil, with laws and morals thrown aside and all men shouting and killing and revelling in joy. Then the liberated Old Ones would teach them new ways to shout and kill and revel and enjoy themselves, and all earth would flame with a holocaust of ecstasy and freedom.

Low claims this passage is a mangled reflection of Crowley’s teachings on the new Aeon and the The Book of the Law. In an article in Societé, Robert North also states that Lovecraft referred to “A.C.” in a letter, and that Crowley was mentioned in Leonard Cline’s The Dark Chamber, a novel Lovecraft discussed in his Supernatural Horror in Literature.

But so what? Lovecraft was a fanatical and imaginative reader, and many such folks are drawn to the semiotic exotica of esoteric lore regardless of any beliefs in or experiences of the paranormal. From The Case of Charles Dexter Ward and elsewhere, it’s clear that Lovecraft knew the basic outlines of the occult. But these influences pale next to Vathek, Poe, or Lord Dunsany.

Desperate to assimilate Lovecraft into a “tradition”, some occultists enter into dubious explanations of mystical influence by disincarnate beings. North gives this Invisible College idea a shamanic twist, asserting that prehistoric Atlantian tribes who survived the flood exercised telepathic influence on people like John Dee, Blavatsky, and Lovecraft. But none of these Lovecraft hierophants can match the delirious splendor of Kenneth Grant. In The Magical Revival, Grant points out more curious similarities between Lovecraft and Crowley: both refer to “Great Old Ones” and “Cold Wastes” (of Kadath and Hadith, respectively); the entity “Yog-Sothoth” rhymes with “Set-Thoth,” and Al Azif: The Book of the Arab resembles Crowley’s Al vel Legis: The Book of the Law. In Nightside of Eden, Grant maps Lovecraft’s pantheon onto a darkside Tree of Life, comparing the mangled “iridescent globes” that occasionally pop up in Lovecraft’s tales with the shattered sefirot known as the Qlipoth. Grant concludes that Lovecraft had “direct and conscious experience of the inner planes,”[9] the same zones Crowley prowled, and that Lovecraft “disguised” his occult experiences as fiction.

Like many latter-day Lovecraftians, Grant commits the error of literalizing a purposefully nebulous myth. A subtler and more satisfying version of this argument is the notion that Lovecraft had direct unconscious experiences of the inner planes, experiences which his quotidian mind rejected but which found their way into his writings nonetheless. For Lovecraft was blessed with a vivid and nightmarish dream life, and drew the substance of a number of his tales from beyond the wall of sleep.

In this sense Lovecraft’s magickal authority is nothing more or less than the authority of dream. But what kind of dream tales are these? A Freudian could have a field day with Lovecraft’s fecund, squishy sea monsters, and a Jungian analyst might recognize the liniments of the proverbial shadow. But Lovecraft’s Shadow is so inky it swallows the standard archetypes of the collective unconscious like a black hole. If we see the archetypal world not as a static storehouse of timeless godforms but as a constantly mutating carnival of figures, then the seething extraterrestrial monsters that Lovecraft glimpsed in the chaos of hyperspace are not so much archaic figures of heredity than the avatars of a new psychological and mythic aeon. At the very least, it would seem that things are getting mighty out of hand beyond the magic circle of the ordered daylight mind.

In an intriguing Internet document devoted to the Necronomicon, Tyagi Nagasiva places Lovecraft’s potent dreamtales within the terma tradition found in the Nyingma branch of Tibetan Buddhism[10]. Termas were “pre-mature” writings hidden by Buddhist sages for centuries until the time was ripe, at which point religious visionaries would divine their physical hiding places through omens or dreams. But some termas were revealed entirely in dreams, often couched in otherworldly Dakini scripts. An old Indian revisionary tactic (the second-century Nagarjuna was said to have discovered his Mahayana masterpieces in the serpent realm of the nagas), the terma game resolves the religious problem of how to alter a tradition without disrupting traditional authority. The famous Tibetan Book of the Dead is a terma, and so, perhaps, is the Necronomicon.

Of course, for Chaos magicians, reality can coherently present itself through any number of self-sustaining but mutually contradictory symbolic paradigms (or “reality tunnels,” in Robert Anton Wilson’s memorable phrase). Nothing is true and everything is permitted. By emphasizing the self-fulfilling nature of all reality claims, this postmodern perspective creatively erodes the distinction between legitimate esoteric transmission and total fiction.

This bias toward the experimental is found in Anton LaVey’s Satanic Rituals, which includes the first overtly Lovecraftian rituals to see print. In presenting “Die Elektrischen Vorspiele” (which LaVey based on a Lovecraftian tale by Frank Belknap Long), the “Ceremony of the Angles,” and “The Call to Cthulhu” (the latter two penned by Michael Aquino), LaVey does claim that Lovecraft “clearly…had been influenced by very real sources.”[11] But in holding that Satanic magic allows you to “objectively enter into a subjective state,” LaVey more emphatically emphasizes the ritual power of fantasy—a radical subjectivity which explains his irreverence towards occult source material, whether Lovecraft or Masonry. In naming his Order of the Trapezoid after the “Shining Trapezohedron” found in Lovecraft’s “The Haunter of the Dark”—a black, oddly-angled extraterrestrial crystal used to communicate with the Old Ones—LaVey emphasized that fictions can channel magical forces regardless of their historical authenticity.

In his two rituals, Michael Aquino expresses the subjective power of “meaningless” language by creating a “Yuggothic” tongue similar to that heard in Lovecraft’s “The Dunwich Horror” and “The Whisperer in the Dark.” Such guttural utterances help to shut down the rational mind (try chanting “P’garn’h v’glyzz” for a couple of hours), a notion elaborated by Kenneth Grant in his notion of the Cult of Barbarous Names. After leaving the Church of Satan to form the more serious Temple of Set in 1975, Aquino eventually reformed the Order of the Trapezoid into the practical magic wing of the Setian philosophy. For Stephen R. Flowers, current Grand Master of the order, the substance of Lovecraftian magic is precisely an overwhelming subjectivity that flies in the face of objective law. “The Old Ones are the objective manifestations…of the subjective universe which is what is trying to ‘break through’ the merely rational mind-set of modern humanity.”[12] For Flowers, such invocations are ultimately apocalyptic, hastening a transition into a chaotic aeon in which the Old Ones reveal themselves as future reflections of the Black Magician (“There are no more Nightmares for us,” he wrote me).

This desire to rebel against the tyranny of reason and its ordered objective universe is one of the underlying goals of Chaos magic. Many would applaud the sentiment expressed by Albert Wilmarth in Lovecraft’s “The Whisperer in Darkness”: “To shake off the maddening and wearying limitations of time and space and natural law—to be linked with the vast outside—to come close to the nighted and abysmal secrets of the infinite and ultimate—surely such a things was worth the risk of one’s life, soul, and sanity!”[13]

In his electronically circulated text “Kathulu Majik: Luvkrafting the Roles of Modern Uccultizm,” Tyagi Nagasiva writes that most Western magic is ossified and dualistic, heavily weighted towards the forces of order, hierarchy, moralizing, and structured language. “Without the destabilizing force of Kaos, we would stagnate intellectually, psychologically and otherwise…Kathulu provides a necessary instability to combat the stolid and fixed methods of the structured ‘Ordurs’…One may become balanced through exposure to Kathulu” (Tyagi’s “mis-spellings” show the influence of Genesis P. Orridge’s Temple of Psychick Youth). Haramullah criticizes black magicians who simply reverse “Ordur” with “Kaos,” rather than bringing this underlying polarity into balance (a dualistic error he also finds in Lovecraft). Showing strong Taoist and Buddhist influences, Haramullah calls instead for a “Midul Path” that magically navigates between structure and disintegration, will and void. “The idea that one may progress linearly along the MP [Midul Path] is mistaken. One becomes, one does not progress. One attunes, one does not forge. One allows, one does not make.”

In the Cincinatti Journal of Ceremonial Magic, the anonymous author of “Return of the Elder Gods” presents an evolutionary reason for Mythos magic. The author accepts the scenario of an approaching world crisis brought on by the invasion of the Elder Gods, Qlipothic transdimensional entities who ruled protohumanity until they were banished by “the agent of the Intelligence,” a Promethean figure who set humanity on its current course of evolution. We remain connected to these Elder Gods through the “Forgotten Ones,” the atavistic forces of hunger, sex ,and violence that linger in the subterranean levels of our being. Only by magically “reabsorbing” the Forgotten Ones and using the subsequent energy to bootstrap higher consciousness can we keep the portal sealed against the return of the Elder Gods. Though Lovecraft’s name is never mentioned in the article, he is ever present, a skeptical materialist dreaming the dragons awake.

Writing the Dream…

Within the Mythos tales, one finds two dimensions—the normal human world and the infested Outside—and it’s the ontological tension between them that powers Lovecraft’s magick realism. Though Cthulhu and friends have material aspects, their reality is most horrible for what it says about the way the universe is. As the Lovecraft scholar Joshi notes, Lovecraft’s narrators frequently go mad “not through any physical violence at the hands of supernatural entities but through the mere realization of the the existence of such a race of gods and beings.” Faced with “realms whose mere existence stuns the brain,” they experience severe cognitive dissonance—precisely the sorts of disorienting rupture sought by Chaos magicians.[14]

The role-playing game Call of Cthulhu wonderfully expresses the violence of this Lovecraftian paradigm shift. In adventure games like Dungeons & Dragons, one of your character’s most significant measures is its hit points—a number which determines the amount of physical punishment your character can take before it gets injured or dies. Call of Cthulhu replaces this physical characteristic with the psychic category of Sanity. Face-to-face encounters with Yog-Sothoth or the insects from Shaggai knock points off your Sanity, but so does your discovery of more information about the Mythos—the more you find out from books or starcharts, the more likely you are to wind up in the Arkham Asylum. Magic also comes with an ironic price, one that Lovecraftian magicians might well pay heed to. If you use any of the binding spells from De Vermis Mysteriis or the Pnakotic Manuscripts, you necessarily learn more about the Mythos and thereby lose more sanity.[15]

Lovecraft’s scholarly heros also investigate the Mythos as much through reading and thinking as through movements through physical space, and this psychological exploration draws the mind of the reader directly into the loop. Usually, readers suspect the dark truth of the Mythos while the narrator still clings to a quotidian attitude—a technique that subtly forces the reader to identify with the Outside rather than with the conventional worldview of the protagonist. Magically, the blindness of Lovecraft’s heroes corresponds to a crucial element of occult theory developed by Austin Osman Spare: that magic occurs over and against the conscious mind, that ordinary thinking must be silenced, distracted, or thoroughly deranged for the chthonic will to express itself.[16]

In order to invade our plane, Lovecraft’s entities need a portal, an interface between the worlds, and Lovecraft emphasizes two: books and dreams. In “Dreams of the Witch-House,” “The Shadow out of Time” and “The Shadow over Innsmouth,” dreams infect their hosts with a virulence that resembles the more overt psychic possessions that occur in “The Haunter in the Dark” and The Case of Charles Dexter Ward. Like the monsters themselves, Lovecraft’s dreams are autonomous forces breaking through from Outside and engendering their own reality.

But these dreams also conjure up a more literal “outside”: the strange dream life of Lovecraft himself, a life that (as the informed fan knows) directly inspired some of the tales[17]. By seeding his texts with his own nightmares, Lovecraft creates a autobiographical homology between himself and his protagonists. The stories themselves start to dream, which means that the reader too lies right in the path of the infection.

Lovecraft reproduces himself in his tales in a number of ways—the first-person protagonists reflect aspects of his own reclusive and bookish lifestyle; the epistolary form of the “The Whisperer in Darkness” echoes his own commitment to regular correspondence; character names are lifted from friends; and the New England landscape is his own. This psychic self-reflection partially explains why Lovecraft fans usually become fascinated with the man himself, a gaunt and solitary recluse who socialized through the mail, yearned for the eighteenth century, and adopted the crabby outlook and mannerisms of an old man. Lovecraft’s life, and certainly his voluminous personal correspondence, form part of his myth.

Lovecraft thus solidifies his virtual reality by adding autobiographical elements to his shared world of creatures, books and maps. He also constructs a documentary texture by thickening his tales with manuscripts, newspaper clippings, scholarly citations, diary entries, letters, and bibliographies that list fake books alongside real classics. All this produces the sense that “outside” each individual tale lies a meta-fictional world that hovers on the edge of our own, a world that, like the monsters themselves, is constantly trying to break through and actualize itself. And thanks to Mythos storytellers, role-playing games, and dark-side magicians, it has.

…and Dreaming the Book

In “The Shadow out of Time,” Lovecraft makes explicit one of the fantastic equations that drives his Magick Realism: the equivalence of dreams and books. For five years, the narrator, an economics professor named Nathaniel Wingate Peaslee, is taken over by a mysterious “secondary personality.” After recovering his original identity, Peaslee is beset by powerful dreams in which he finds himself in a strange city, inhabiting a huge tentacle-sprouting conical body, writing down the history of modern Western world in a book. In the climax of the tale, Peaslee journeys to the Australian desert to explore ancient ruins buried beneath the sands. There he discovers a book written in English, in his own handwriting: the very same volume he had produced inside his monstrous dream body.

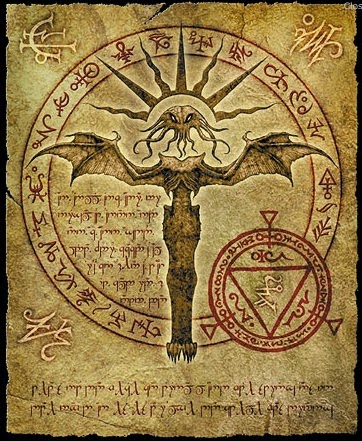

Though we learn very little of their contents, Lovecraft’s diabolical grimoires are so infectious that even glancing at their ominous sigils proves dangerous. As with their dreams, these texts obssess Lovecraft’s bookish protagonists to the point that the volumes, in Christopher Frayling’s phrase, “vampirize the reader.” Their titles alone are magic spells, the hallucinatory incantations of an eccentric antiquarian: the Pnakotic Manuscripts, the Ilarnet Papyri, the R’lyeh Text, the Seven Cryptical Books of Hsan. Lovecraft’s friends contributed De Vermis Mysteriis and von Junzt’s Unaussprechlichen Kulten, and Lovecraft named the author of his Cultes Des Goules, the Comte d’Erlette, after his young fan August Derleth. Hovering over all these grim tomes is the “dreaded” and “forbidden” Necronomicon, a book of blasphemous invocations to speed the return of the Old Ones. Lovecraft’s supreme intertextual fetish, the Necronomicon stands as one of the few mythical books in literature that have absorbed so much imaginative attention that they’ve entered published reality.

If books owe their life not to their individual contents but to the larger intertextual webwork of reference and citation within which they are woven, than the dread Necronomicon clearly has a life of its own. Besides literary studies, the Necronomicon has generated numerous pseudo-scholarly analyses, including significant appendixes in the Encyclopedia Cthulhiana and Lovecraft’s own “History of the Necronomicon.” A number of FAQs can be found on the Internet, where a mild flame war periodically erupts between magicians, horror fans, and mythology experts over the reality of the book. The undead entity referred to in the Necronomicon‘s famous couplet—”That is not dead which can eternal lie,/And with strange eons even death may die”—may be nothing more or less than the the text itself, always lurking in the margins as we read the real.

Lovecraft’s brief “History” was apparently inspired by the first Necronomicon hoax: a review of an edition of the dreaded tome submitted to Massachusetts’ Branford Review in 1934.[18] Decades later, index cards for the book started popping up in university library catalogs.

It’s perhaps the principle expression of Lovecraft’s Magick Realism that all these ghostly references would finally manifest the book itself. In 1973, a small-press edition of Al Azif (the Necronomicon’s Arabic name) appeared, consisting of eight pages of simulated Syrian script repeated 24 times. Four years later, the Satanists at New York’s Magickal Childe published a Necronomicon by Simon, a grab bag that contains far more Sumerian myth than Lovecraft (though portions were “purposely left out” for the “safety of the reader”). George Hay’s Necronomicon: The Book of Dead Names, also a child of the ’70s, is the most complex, intriguing, and Lovecraftian of the lot. In the spirit of the master’s pseudoscholarship, Hay nests the fabulated invocations of Yog-Sothoth and Cthulhu amongst a set of analytic, literary and historical essays.

Though magicians with strong imaginations have claimed that even the Simon book works wonders, the pseudohistories of the various Necronomicons are far more compelling than the texts themselves. Lovecraft himself provided the bare bones: the text was penned in 730 A.D by a poet, the Mad Arab Abdul Alhazred, and named after the nocturnal sounds of insects. It was subsequently translated by Theodorus Philetas into Greek, by Olaus Wormius into Latin, and by John Dee into English. Lovecraft lists various libraries and private collections where fragments of the volume reside, and gives us a knowing wink by noting that the fantasy writer R.W. Chambers is said to have derived the monstrous and suppressed book found in his novel The King in Yellow from rumors of the Necronomicon (Lovecraft himself claimed to have gotten his inspiration from Chambers).

All of the Necronomicon’s subsequent pseudohistories weave the book in and out of actual occult history, with John Dee playing a particularly conspicuous role. According to Colin Wilson, the version of the text published in the Hay Necronomicon was encrypted in Dee’s Enochian cipher-text Liber Logoaeth. Colin Low’s Necronomicon FAQ claims that Dee discovered the book at the court of King Rudolph II’s court in Prague, and that is was under its influence that Dee and his scryer Edward Kelly achieved their most powerful astral encounters. Never published, Dee’s translation became part of celebrated collection of Elias Ashmole housed at the British Library. Here Crowley read it, freely cobbling passages for The Book of the Law, and ultimately passing on some of its contents indirectly to Lovecraft through Sophia Greene. Crowley’s role in Low’s tale is appropriate, for Crowley certainly knew the magical power of hoax and history.

For the history of the occult is a confabulation, its lies wedded to its genealogies, its “timeless” truths fabricated by revisionists, madmen, and geniuses, its esoteric traditions a constantly shifting conspiracy of influences. The Necronomicon is not the first fiction to generate real magical activity within this potent twilight zone between philology and fantasy.

To take an example from an earlier era, the anonymous Rosicrucian manifestos that first appeared in the early 1600s claimed to issue from a secret brotherhood of Christian Hermeticists who finally deemed it time to come above ground. Many readers immediately wanted to join up, though it is unlikely that such a group existed at the time. But this hoax focused esoteric desire and inspired an explosion of “real” Rosicrucian groups. Though one of the two suspected authors of the manifestos, Johann Valentin Andreae, never came clean, he made veiled references to Rosicrucianism as an “ingenius game which a masked person might like to play upon the literary scene, especially in an age infatuated with everything unusual.”[19] Like the Rosicrucian manifestos or Blavatsky’s Book of Dzyan, Lovecraft’s Necronomicon is the occult equivalent of Orson Welles’ radio broadcast of the “War of the Worlds.” As Lovecraft himself wrote, “No weird story can truly produce terror unless it is devised with all the care and verisimilitude of an actual hoax.”[20]

In Foucault’s Pendulum, Umberto Eco suggests that esoteric truth is perhaps nothing more than a semiotic conspiracy theory born of an endlessly rehashed and self-referential literature—the intertextual fabric Lovecraft understood so well. For those who need to ground their profound states of consciousness in objective correlatives, this is a damning indictment of “tradition.” But as Chaos magicians remind us, magic is nothing more than subjective experience interacting with an internally consistent matrix of signs and affects. In the absence of orthodoxy, all we have is the dynamic tantra of text and perception, of reading and dream. These days the Great Work may be nothing more or less than this “ingenius game,” fabricating itself without closure or rest, weaving itself out of the resplendent void where Azathoth writhes on his Mandelbrot throne.

Footnotes

[1] “The Haunter of the Dark,” The Best of H.P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre (New York: Ballantine, 1963), p. 220.

[2]Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press). “The anomalous is neither an individual nor a species; it has only affects, it has neither familiar or subjectified feelings, nor specific or significant characteristics. Human tenderness is as foreign to it as human classifications. Lovecraft applies the term ‘Outsider’ to this thing or entity, the Thing which arrives and passes at the edge, which is linear yet multiple, ‘teeming, seething, swelling, foaming, spreading like an infectious disease, his nameless horror.'” (244-5) “What we are saying is that every animal is fundamentally a band, a pack…It is at this point that the human being encounters the animal. We do not become animal without a fascination for the pack, for multiplicity. A fascination for the outside? Or is the multiplicity that fascinates us already related to a multiplicity dwelling within us? In one of his masterpieces, H.P. Lovecraft recounts the story of Randolph Carter, who feels his ‘self’ reel and who experiences a fear worse than that of annihilation: ‘Carters of form both human and nonhuman, vertebrate and invertebrate …. etc'”(240)

[3] Ibid., p. 202

[4]One notable exception to this is The Starry Wisdom, D.M. Mitchell’s recent British collection of Mythos tales and art that bristles with experimental and chthonic magick (London: Creation Books, 1994). Contributors range from J.G. Ballard and William S. Burroughs to Grant Morrison and Alan Moore, two of today’s most intelligent comic book writers. Though the bios make no mention of the fact, a number of the contributors, including Don Webb, are solid occultists. On the other hand, the author of one of the more perverse tales is Robert M. Price, a New Testament scholar and pastor of the First Baptist Church of Montclair, New Jersey.

[5] Fritz Leiber, Jr., “A Literary Copernicus,” in S.T.

Joshi, et., H.P. Lovecraft: Four Decades of Criticism (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1980), p. 51.

[6] S.T. Joshi, H.P. Lovecraft (Mercer Island, Wash.: Starmbat House, 1982), p. 58.

[7] He was also the first modern occultist to anticipate Lovecraft by trafficking with explicitly extraterrestrial entities.

[8] See Nadia Choucha’s Surrealism and the Occult (Vermont: Destiny Books, 1991), pp. 51-74.

[9] Colin Wilson, “Introduction,” in George Hay, ed., The Necronomicon: The book of Dead Names (London: Corgi, 1978), p. 35.

[10] The Necronomicon FAQ Version 2.0, written and compiled by Kendrick Kerwin Chua (kchua@unf6.cis.unf.edu), May 1994.

[11] Anton LaVey, The Satanic Rituals (New York: Avon, 1972).

[12] Private email correspondence.

[13] “The Whisperer in Darkness,” op. cit Best of…, p. 162.

[14] Joshi, p.32.

[15] The imaginative production of a role-playing game’s “virtual reality” is not dissimilar to ceremonial magic. RPGs consist of a defined space and time; random dicethrows; source books; a game system that organizes numbers, rules and characteristics; and, most importantly, the active imagination of the players. Organized magical rituals follow a superficially similar scheme: a coherent and graded system carves out a performative space and time wherein divinatory randomness, data from occult cookbooks, and symbolic networks of numbers and signs come to life within the active imagination of the mage, a “playful” imagination that calls forth–and even becomes–the autonomous “characters” of the gods.

From ancient ritualistic board games to the Golden Dawn’s Enochian Chess, games have been vehicles for magic and divination. Recently Chaosium, the publisher of Call of Cthulhu, has cemented the connection with Nephilim, the first explicitly occult role-playing game. You play one the Nephilim, a race of magical beings who battle secret societies and must take over living human hosts in their quest for enlightenment. Already banned in some stores, Nephilim artfully and systematically melds deep and genuine esoteric arcana (kabbalah, alchemy, astrology) with an original variant of the occult conspiracy theory of history.

[16] Following the logic of the Freudian slip, Spare workings such as sigil magic must be “forgotten” in order for their encoded intention to “break through” into reality.

[17] August Derleth collected Lovecraft’s letters about his dreams in Dreams and Fantasies (Suak City, Wis.: Arkham House, 1962).

[18] op. cit, Chua.

[19] Quoted in Roland Edighoffer,”Rosicrucianism,” in Antoine Faivre and Jacob Needleman, eds., Modern Esoteric Spirituality (New York: Crossroads, 1992), p. 198.

[20] Quoted in S.T. Joshi, “Afterword,” in H.P.Lovecraft, The History of the Necronomicon (West Warmick, R.I.: Necronomicon Press, 1980), p.9