Listening to musicians listening

I get a large number of promotional CDs, though thankfully fewer than the crateloads of crap that sailed my way over a decade ago, when I was an aggressive and hoarding rock critic. Believe me: it was no picnic obsessively sifting through grunge and hip hop back in the heyday of the CD, and I did it all for you. I still listen to almost everything, although that means I rarely get back to even the resonant recordings more than a couple times unless I’m writing about the thing.

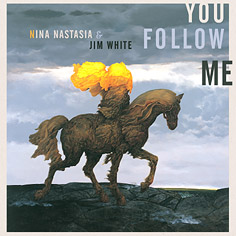

The major exception to this trend this summer has been Nina Nastasia and Jim White’s collaboration You Follow Me, which has now hit the wires and which I’ve had lying around for a couple months. This is the disc that keeps coming back to me, when I’m listening to it and when I’m not. I’m not talking about the crack-pipe insistence of the true sonic virus, like Animal Collective’s new “For Reverend Green” or this lazy Johnny Osbourne tune “Right, Right Tune” that’s on the new Summer Records comp that I can’t stop playing.

With You Follow Me, I mean something more intrigued and spacious–like a crush that begins with perplexity and a vague disquiet rather than lust or bliss. At first I thought the idea of an acoustic singer-songwriter making a record with nothing more than a drummer a bit precious and reaching, a sign of a genre flopping like a fish on the floor. I dug Jim White’s work with the Dirty Three, but I just didn’t get it at first.

I hadn’t heard Nastasia before, even though I really like music like hers, and I didn’t realize how much smarts went with the bittersweets. Her last record, On Leaving, has a handful of gorgeously evocative tunes, riding conventional chords, delivered with a strong voice, alluring and honeydark, and dusted with the reflective melancholy that, for me, is as necessary to the genre as Cookie Monster is to black metal. But there is a fundamental truth about singer-songwriters that we all must bow before: it is a beat form. I say that as a stone-cold lover of the genre, a lifelong addict of Joni Mitchell and Elliot Smith and Nick Drake and newer folks who don’t come quite as readily to mind. And there is nothing wrong with beat forms; I mean, I am regularly charmed by madgrigals. But however moving and sweet it can be to listen to a strong woman wrenching forth something like her self on an acoustic guitar, the form is playing itself out even as she plays.

You Follow Me is not only deeply affecting music, but it is wise and probing music, a brilliant intervention in genre. In the quest to open up folk form–don’t make me define it, but you know what I mean–lots of bands this last spell have opened up the guitar and the song to druggy, improvisatory strategies of deferral and play. But here Nastasia sticks with solid and formally conventional songs, while White tickles like an experimentalist with a down-home heart, providing straight-up support on some songs but always threatening to skitter into an elegant chaos that occasionally overwhelms the song, pulling against Nastasia’s basic pulse.

White’s most wacky-assed performance also makes the masterpiece here. “Our Discussion” is Nastasia’s elliptical reflection on the subtle exchanges–the words and gestures and shared atmospheres–that pass between lovers who are passing between each other. As a singer-songwriter’s song, it’s probably the most moving tune on the record, and mature in the best of senses. The chorus is resolved but tender, plaintive and strong and shorn of nostalgia:

I dont believe in the power of love

I dont believe in the wisdom of stone

I dont believe in a god or the mind

And I’m not alone

Nastasia’s finger-picking pattern is nothing special, and the minor chords you’ve heard a thousand times before. But Jim White gets totally loose and shifty-fingered, and for nary a pulse lands on the backbeat. Skittering, slipping, and, most importantly, listening, White skips like a savage jazzbo across the tightrope that keeps this gentle, ordinary folk tune together.

Then you realize that “Our Discussion” is not just about another one of these floating figures of desire and regret that haunt Nastasia’s lyrics. It’s also about White, and making music, and the conversation implicit in improvisation and collective composition alike. So the discussion is both Nastasia’s chat with her guy, and her collaboration with White. But it’s not that the music illustrates the lyrics; it’s that the musical conversation itself has been raised to the complexities of human interaction.

It reminds me of my most transcendent experience drumming. I studied a bit of Ghanese polyrhtyhms, and I like hippy drum circles, but I’m not good or anything. Sometimes I can play decently, though my being decent has almost everything to do with my ability to listen to the beats bubbling out from between the dreadlocks and responding with simple patterns that help organize and shape the nuttiness.

That night, over a decade ago, I found myself in a crowd of dozens of random drummers, half naked beneath the desert nightsky and pressing in towards the toxic pyre of a sacrificed wooden man. I was pounding out bass lines on an empty 5-gallon water jug awkwardly lodged beneath my left arm. The circle was hot, the vibe was tribal, and my reason was gone gone gone. Then, out of the forest of sounds that surrounded me, I heard another drum, a much more sophisticated drum, and it was speaking to me. More accurately, it was teasing me, although it also encouraged me to offer my own retorts and challenges. I knew it as surely as you know when you’ve finally gotten a human being after a ramble through an automatic phone tree: I was having a discussion.

Of all musical instrument, drum beats are closest to words, not to say philosophy, and the relation of drummers to one another in an informal circle is a model of social interaction, the sad truth of which is that lots of people don’t listen much or share. But rarely does a sensitive, improvising drummer listen so hard to a girl singing an intimate folk song. And it’s even rarer that, for “Our Discussion,” they’re in such accord.

For this tune, White’s relationship to the four beat that rules popular music is as elliptical as Nastasia’s words, and both are as elliptical as the emotions that pass between us in relationship. White also resists slipping into a satisfying groove at the killer chorus, just like Nastasia sometimes resists giving us the final line about being “not alone,” a lacuna that leaves us hanging like John Dowland does at the end of “In Darkness Let Me Dwell.” The chords are aching, and deeply familiar, and part of us wants to hear the backbeat. But White does not give in. He intensifies, but he just rides. May we all navigate so.