The hidden lessons of a flight that skirted hell

I just returned from a couple weeks in Costa Rica, where I spoke at the semi-annual Mindstates conference and tooled around with some pals. I had hoped to herein recount some of the highlights of the trip, perhaps in an attempt to make up for my unmitigated posting sloth during the last fortnight, a laziness that was no doubt partly inspired by the actual sloths I saw blissfully konked out in the jungle foliage. But about the only thing on my mind right now is the hell-flight we endured on the return home.

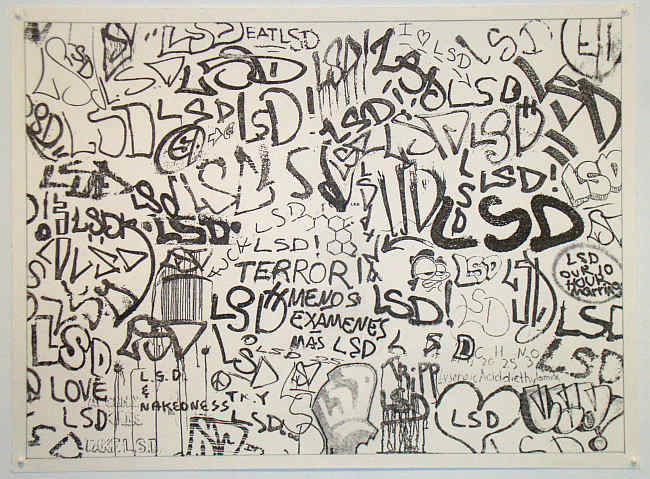

At the conference I gave a talk on Philip K. Dick and led a vigorous group discussion about the filmmaker Richard Linklater’s essayistic dream-film Waking Life, which is kinda like Sans Soleil for stoners. One of my major themes in these discussions was what Tibetans call the bardo: the insubstantial in-between state said to confront the soul after death, when the contents of mind return to seduce and terrify the ego’s disoriented after-image as it reverberates into rebirth. A Dantesque funhouse of ravenous demons, smoky lights, and copulating parents-to-be, the bardo is no doubt one of the most evocative sacred accounts of the afterlife.

It may also be one of the most useful. Early in Waking Life, the Ethan Hawke character quotes Timothy Leary to the effect that, even if nothing of us survives death, the last few minutes of the brain’s electrical activity may be experienced by the dying person as an entire life racing in time-lapseor, as the film itself suggests, a nearly infinite labyrinth of dreams. From this perspective, the traditional teachings of bardo navigation may come in handy despite the basic reality of brain-death: even if we are only riding that last wave to flatline, it pays to know how to surf.

My other major point was that there are bardos everywhere — not just in death, but in dream, in the transitions between waking and sleep, in sneezing and orgasm and the collapsing realities of Philip K. Dick novels. Death is simply the starkest transition; we are always undergoing the dissolution of the world (especially these days, when epochal change is assured).

Traveling, in its many guises, can be another bardo rehearsal, offering up hints and foreshadows, perhaps even a few tricks and tips. And I am not just talking about the trials and delights of shoestring journeying through exotic and challenging backwaters where sacred images still hold sway. I am also talking about the grueling, mind-altering reality of twenty-first century commercial air travel.

Say you are me, and you conclude your Costa Rican trip at the airport in San Jose. You step out of the world of place, of birdcalls and smog and wet air, and enter an air conditioned terminal, formally similar to thousands of other spaces across the globe. The terminal is the gateway to of an interzone of nowheres, a network of liminality, of thresholds and passageways and vehicles designed by the principalities of the air to move and distribute large populations of souls to their destinies — or at least their destinations. Terminal. What other journey, you might ask, begins at the end?

Moving through this system is, despite all the hubbub, a remarkably passive process, a submission that begins with the loss of you body — or at least with its relative autonomy and comfort. Lined up and forcibly unshod and radiated and patted down, your body is no longer your own, even before it reaches its final inflight resting place, a seat that demands medieval metaphors — monk’s cell, Iron Maiden, rack. Of course, before you strap yourself in to the mercy seat, a subtler torture of the spirit is provided by your journey through the first class cabin. This brief march through the Elysian fields of legroom goads the envious into remorse while restoring the otherwise forgotten theological category of the elect.

This is where my recent bardo trip really began. I was sitting in my coach seat on American flight 2614, waiting for the doors to close, when a young woman wearing some vaguely official garb walked up the aisle, asked if I was Erik Davis, and then beckoned me to follow her off the plane. In the gangway I met two young Costa Rican men in plain clothes, with ordinary airport security badges dangling around their necks. One asked if I spoke Spanish (“un poquito”), and the other mumbled something about my “madre.” My bafflement now mutating into fear, I flashed on the worst case scenario: my mother is dead, and these functionaries are here to break the news.

Seeing my concern, the young woman clarified that the gentlemen were after my mother’s maiden name, which I gave them, along with the demand that they explain why they cared to know. Her English was not much better than my Spanish, but she explained that my name was on a Costa Rican no-fly list. I asked for clarification from one of the men, but he just smiled nervously as his partner got on the phone to, apparently, pass on the proverbial name. I wrote down my own given name, underlining the relatively rare “k” — the sole mark of distinction in an otherwise generic name — but he just smiled and scribbled a “c” alongside the k. The other guy got off the phone, and I started to get mad, but then the first fellow grinned again, shook his head and said “OK OK no problem.” They ushered me back on the plane, leaving me and my buddies to ponder the imponderables: Whose “no-fly” list? Did they actually have a record of my mother’s maiden name? Why would they think I wouldn’t just lie? All of which really boiled down to one question:

What the fuh…?

It seems as if all those Philip K. Dick novels were coming home to roost, and if the rest of the journey was more of your typical commercial airline hell, it remained permeated with the woozy disorientation caused by mistaken identity and the arbitrariness of the archons who rule these transit zones.

My nausea was hardly alleviated by the greasy nuts and the Diet Coke and the Barney songs that cackled from some tyke’s portable DVD player in the next row. Meanwhile, terrible and unusual storms — you know, the kind that are now business as usual — forced us to circle over Dallas for awhile before we landed and sat on the tarmac for almost an hour, first to allow the gate to clear, and second to allow the lightning strikes that froze ground service to make their way elsewhere.

We made it through customs and immigration quite quickly, despite the general chaos the storm had brought to American’s hub. We soon discovered that our flight to San Francisco had been cancelled, and lined up to talk to one of the two, count em, two service agents who had been dealing with this shit all day. As our fellow searched for an alternate route — finally setting us on a flight to Reno and a US Airways hop to SF the next morning, which he nonetheless screwed up in ways I will not bother to recount — the line behind us grew and grew. Soon scores of frantic, fatigued, and harried customers stood and fidgeted, frustrated and angry, a line of refugees that grew into an anxious mob. I had not thought a single storm could have undone so many.

I will not continue to enumerate the slings and arrows that still lay in store for us, though its important to mention that they included panicked dashes, confiscated shaving cream, lost luggage, telephone hold lines that switched impishly into dial tones, booked hotels, room 666, and a host of largely lame encounters with service agents and other dwellers of the threshold, most of whom were incompetent and frazzled, and a few of whom were kind and helpful enough they seemed almost angelic.

Suffice it to say that the only redemption lay in seeing it all as the bardo, whose deepest teaching seems to be that our uncontrolled fears, desires, and hatreds boomerang back tenfold. And I am sad to report that, unless the temper shapes up, I am probably doomed to flit about some angry little maze of hell whose labyrinthine torments resembled the endless branchings and recursions of the most fiendish and robotic phone trees. “If you would like to hear your options again…”

Romantics complain that we moderns have lost all rites of passage, but commercial air travel remains a fact of life that is both a rite and a passage, although it is a rite whose liminality and duress no longer offer transformation. The rewards are always later; in the meantime, we simply throw ourselves on the altar of an anxious, discombobulating drift.

Through the windows on the flight to Reno, J and I watched magnificent explosions of lightning in the thunderclouds, Dr. Frankenstein displays that almost made up for all the horrors. In flight, we sometimes glimpse the awesomeness of heaven and earth through the portholes, visions of clouds and lightning and deep blue black. But when we turn forward to look where we are going, all we face is another cell, another idiot screen, another prisoner chained to the galley. The words of the metaphysical English poet Henry Vaughn come to mind:

Man is the shuttle, to whose winding quest

And passage through these looms

God ordered motion, but ordained no rest.