Breton Megaliths and parish closes

Brittany, the northwestern départment of France much beloved of French tourists, is one of those enchanted places that form a Celtica countercurrent to the national maps of Europe, bridging the UK cluster of Cornwall, Ireland, and Scotland with Galicia to the south: a webwork of faded faerie lore, paganish Christianity, nasal pipe music, and hard cider (at least in Cornwall and Brittany). As in the UK, the province is also littered with ancient Neolithic structures. I didn’t have my shit together enough to buy a GPS unit and download location data before hand, and so our—or, as my wife would rewrite the sentence, my—megalithomania was checked by bad tourist maps and only marginally better French. But we still managed to hunt down quite a few amazing sites in just a few days driving around the province.

The contemporary culture of Brittany has less of the warmth, magic, and overall baba-coolio of the South, but the stones more than made up for the staid vibe, not to mention the terrific expense incurred by the pesos we found that we were holding in our wallets. As mentioned, the place is lousy with megaliths: menhirs (single standing stones), dolmens (single-chambered burial chambers with flat slab roofs), and the elongated dolmens called passage graves. (There are few if any circles that I know of.) We didn’t have time to do more than glimpse one small cluster of Carnac’s well-known and impressively large alignments, which largely follow the roads, but we did visit the huge and deeply enchanting La Roche aux Fees, a massive gallery grave that was once covered with earth but now stands bare-bones beside a cozy little picnic park down some rural lane, next to a gnarled ancient oak who lords over the ancient bone room with spooky dominion.

Many of the other sites we saw were more modest, tucked in the back of a field or behind a row of houses, their humble persistence and relative obscurity oftentimes lending them greater atmosphere than some of the more charismatic and well-mapped spots.

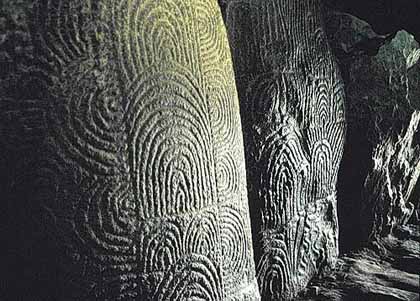

By far the most impressive of the sites was Gavrinis, a tiny uninhabited dollop of land in the bay near Carnac whose name might mean Goat Island (goats and ancient gods go well together). In my ignorance, which somehow never ceases to amaze me, I had never heard of this great place: a massive engraved passage grave still beneath its tumulus, a site that (my wife says) rivals New Grange and certainly has the most impressive Neolithic pictographs I have ever seen with my naked peepers. Unfortunately, the chipper, deeply enthusiastic guide, a professional archeologist who spoke wonderfully clear French, insisted we not take photographs, so here is a shot lifted from the global brain.

In the end, I spent most of my time quickly sketching, which was probably more revealing, as it enabled me to get inside the curious patterns, to pick up on some of their inner twists and turns.

The guide spent most of the time interpreting these largely abstract patterns and swirls according to a hidden representational logic that was more interesting in what it said about the hermeneutics guiding Neolithic experts than about the images before me. She saw axes and staffs; I saw fields of energy, inner-eyelid vibrations, Deleuzian struggles of smooth and striated spaces, budding fractals, the abstract origins of Buddha’s mysterious top-knot. And even if the swirling marvels did encode idols and kings and the tools of animal husbandry, these images were so mutated by the resonating lines that they opened up a space that refused to be reduced to material conditions or collections of knowledge, but instead radiated outward in a cosmic effulgence we only dimly recognize in our word art.

Megaliths are not Brittany’s only enchanted stones. The other tourist destinations that moved me mightily were a handful of churches and parish closes in Finistère, the spectacularly beautiful northwest region of Brittany. Closes are the walled areas that surround parish churches, often along with charnel houses, burial grounds, and freestanding statuary. We saw a few elven doorways and crazy baroque altars, but once again, carved stone ruled, expressing the unique tenor of popular Bretagne Catholicism of the rural (and hence still rather medieval) Renaissance: green men peering out from porches and lintels; goofy saints leaning down from niches in a popular parody of High Gothic; devils writhing in the pain of holy water fonts.

Most amazing, though, were the Calvaries. Named after the skull hill where Jesus was crucified, the Calvary is a heavily sculptured outdoor crucifix unique to Brittany. In addition to the usual hanging Christ, the Calvary’s massive bases are covered with sculptured scenes illustrating the life of Jesus. The combined effect is like a three-dimensional sacred comic book, charming and imaginatively potent.

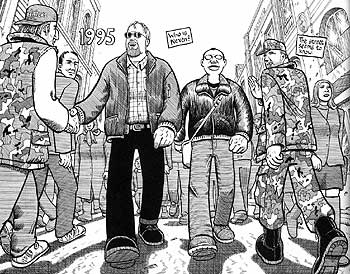

The carvings on the best Calvaries I saw—especially the celebrated one at Guimiliau—were immensely appealing, conjuring up some of my favorite aspects of comic book art: static panels exploding with narrative force; richly defined lines that hover between archetype and caricature; an air of fable and fairy-tale; a slight exaggeration in bodies that makes them both dreamlike and intensely physical. This one fellow on Guimiliau’s Calvary —taking off his sandals to get his feet washed by JC—reminded me very much of Joe Sacco’s figures.

With their vividness and immediacy, these sculptures typify popular Christian art, and popular Christian art often has a more down-home, almost paganish appeal, tied as it is to the concrete desires and imaginations and needs of rural folk. And it was just this popular spirit that redeemed the last great stone we saw before returning to Paris and grim, anxious America. I had read that a number of Brittany’s menhirs had been Christianized, and we passed a few humble stones that had metal crosses nailed to the tops of their lozenge-shaped faces. So it was with some trepidation that I sought out a massive single standing stone near the town of Perros-Guirec, as it was described as being similarly marked with Christian imperialism. Instead I saw something that expressed that subtler and altogether more rare sense of genuine, life-affirming syncretism that infuses Celtic Christianity.

The images carved into the top of the stone are all the objects associated with the crucifixion, and they include the non-canonical but traditional image of Veronica’s veil beaming out in the center. (History’s first spiritualist photograph, the archetype of the shroud of Turin, Veronica’s veil is the name of the hanky that Veronica—whose name means “true icon”–used to wipe the sweat from Jesus’s brow on his way to Calvary, and which magically retained the image of his face.) Yet somehow they seemed to even more deeply enchant the rockface. If the medieval Bretons had hated the stones and found them devilish, there would be a lot fewer of them; what I see here are engravings that reclaim for late medieval imaginations what must have been honored but mysterious reminders of a strange but still poetic past.