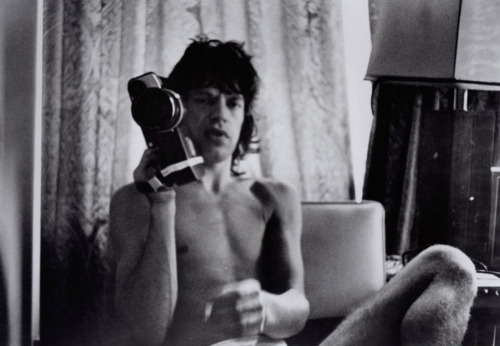

Robert Frank’s Rolling Stones slop-doc

Finally got a chance to see Cocksucker Blues, photographer Robert Frank’s rarely-seen spooge doc on the Rolling Stones during their 1972 American tour. I went on craigslist to sell some Grateful Dead paraphernalia and a grey market DVD had just been posted and it was only twelve bucks and seemed like a sign so I got it. I’ve been on a Stones kick lately, re-affirming my great love for the great records, even as I become more convinced that their most passionate music is animated by an almost reptilian void. Last week, a pal down south told me his favorite Stones record was Aftermath—the British version—but I had to respond that I followed the herd with Exile, when they were the most drugged out and open to the deep dark currents that flowed through their music. They were able to craft an Americana that was more of the spirit then the letter, and hence a deeper Americana.

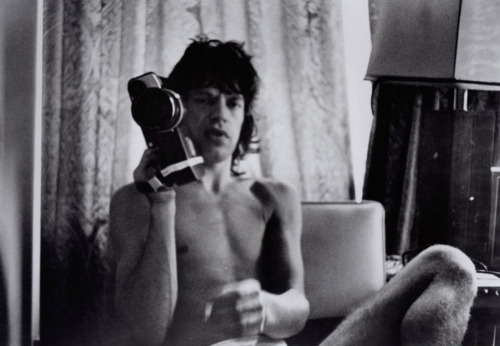

The Frank movie was altogether more brazen, intelligent, hilarious, and repulsive than I expected. I can see why the band tried and half succeeded to suppress it, but it is the perfect vehicle for the band’s empty power. Though the film was slapdash in style, it was not the formal mess I had once been led to believe. The scarves and needles and whiskey bottles and boobs were all perfectly in place, and the random slices of tour life fit together like the collage on the cover of Exile, creating probably the best—the truest? the frankest?—portrayal of life the road in all its boredom, delirium, and logistical haze.

An Altmanesque soundtrack of overdubs, drug mumbles, and raw live clips glues the images together without making them any more coherent. The TV is everywhere, providing a soundtrack of aspirin ads and band interviews and news that becomes part of the visuals when Keith and a pal toss a hotel tube off a balcony and giggle like stupid kids. Tour life looked like a tawdry romper-room, and the ridiculous ambience of drugs and groupie cavorts eviscerated my envious romance with 70s rock stars, though I am sure the dreams will return.

Anyway, if such foolishness is the price of such music, I’ll let them pay it. Live they blazed, Keith sneering through the guitar, Mick sinuous, gawky, and serpentine beyond all reason or gender. The dark devotion to their music is palpable; mid-flight on a tour airplane, the boys create an informal rhythm section while groupies get fucked, and their beats tambourine shakes seem ritualistic. To interviewers, the dynamic duo talked liked idiots or cagey girls, but when they hunch around a single of “Happy” in a hotel room, wondering if the mix should be mono and how the bass sounds, the focus is all there. Canny lads with preternatural talents, having a muddy field day with the music that clothed their snark and swagger with excellence.

Sociologically, the most impressive aspect of the world Frank recorded was the ease and mutual amusement expressed by the white folks, Brits and Yanks, and the various black Americans they interact with and engage throughout the film, from an incandescent onstage Stevie Wonder to various bouncers, singers, cooks and pool players. The handoff of rock from black to white seemed more complex and even respectful. Or maybe it was the times—the long bummer of the early 70s—but there was a hazy, wasted looseness around the self that undermined even the most charged identities.

That’s the thing about the slop: we are all in it together, even the pampered rock stars with their jump suits and Dionysian blues. Even they are torn and frayed.