Shards of the Diamond Matrix

In January, while attempting to scrounge up my first assignment for Wired, I visited a Tibetan Buddhist monastery located in the Indian state of Karnataka. Along with their usual tasks, the young monks at Sera Mey were inputting rare and crumbling woodblock sutras onto cheap XTs. Under the auspices of the Asian Classics Input Project, mountains of this digital dharma eventually found its way onto freely-distributed CD-ROMs and the Internet.

One evening, after the monks served me a bowl of noodles and beef my vegetarian self choked down out of politeness, an older monk sidled up to the table. Furtively he reached into his maroon robes and handed me a thick dog-eared notebook, wrapped in a pair of sweat socks. He made sure I secured the book in my satchel, but when I asked what was going on, he only smiled, bowed and walked quickly from the dining hall.

I unwrapped the package late that night. The words “Open the Folds!!” were scrawled on the notebook cover and the sticky pages gave off a faint odor of opium. The yellowing pages were covered with a minute, seemingly impenetrable scrawl. Like a printed circuit or a magical grimoire, the indecipherable density of these bug doodles signified, and when I returned to the States, a microscope confirmed my suspicions: the scrawl was a dense molecular text, written in English, and employing a curious variant of the arcane Chinese art of microscopic calligraphy.

The author himself turned out to be no less arcane, though in a manner far closer to home. His name was Lance Daybreak, and a subsequent call to a Southern California pop historian corroborated his claim to be one of the first surfers to hang around the Santa Monica pier in the late 1940s. In fact, all Daybreak’s assertions about his Stateside activities checked out. After getting his B.A. in archeology from UCLA in under two years, he did a long stint as a merchant seamen and treasure hunter. In 1965, he enrolled in Stanford, where he was working on a thesis that combined Maturana’s cybernetics with Nagarjuna’s second-century Madhyamika Buddhist philosophy in order to solve some dizzying problems in data sets and computational linguistics. Socially, Daybreak covered all the fronts: he huffed it over the Bay Bridge for SDS actions, designed psychedelic light shows for the Pranksters and the Family Dog, and cranked out idiosyncratic code with the hackers at SAIL. In 1968, Daybreak either dropped out or was expelled. On July 20, 1969, the day Apollo 11 landed on the moon, the man left for Asia.

It’s here that Daybreak’s tale becomes pretty ludicrous. In the manuscript, he claims to have somehow eluded the Soviet authorities and entered East Turkestan. There, in the savage gullies of the Karakorum Mountains, a few hundred kilometers southwest of the Taklamakan Desert, on the southern fork of the ancient Silk Road, he “discovered” an unknown and isolated people — the ngHolos. Though the lay ngHolos had settled down into a sedentary life of subsistence farming, weaving, and hash-growing, the community’s religious order of monks and nuns, known as the Virtuous Ones remained nomadic. The Virtuous Ones wandered on foot or horseback through the “Folds:” the high passes, hidden valleys, and endless plateaus of their severe mountain surroundings. But Daybreak’s descriptions also make it clear that for the Virtuals, this bleak physical environment “unfolded” into an abstract, visionary realm, a constantly-shifting locus of cosmic memory and oracular landscapes haunted by demons, “alien gods” and insectoid Buddhas. Daybreak repeatedly cites one of the ngHolo’s countless slogans: Here your eye does not follow the warp of the land. Here you follow the warp of your own eye.

To judge from his tone, Daybreak does not seem to have gone insane or sunk into the mire of narcotic psychosis. I choose to read his text as I read Castaneda, with an open mind not particularly concerned with anthropological accuracy I wouldn’t really be able to judge anyway. In any case, from the fragments I’ve been able to decipher, the Virtuous Ones — or “Virtuals,” as Daybreak sometimes calls them — are fascinating. Their radically eclectic and syncretic religious philosophy juggles elements from the various faiths that passed along the Silk Road — gnostic Manicheanism, Mahayana Buddhism, Mongolian shamanism, Catholicism, heretical Sufism, Taoism — without trying to tie them up into one grand system.[1] As Daybreak writes, “The path is a network of paths.”

Even more fascinating that the ngHolo’s religious collages are their spiritual machines. In the early 17th century, a Jesuit named Francis Lumiere brought the first clock to the region. Daybreak writes: “Having long since assimilated whatever Christian motifs that compelled them, the ngHolos found the man’s uncompromising theology obnoxious and his clothes in poor taste. But they loved his machine.” The lay community put great store in their bronze prayer wheels, whose constant revolution supposedly generated the compassionate energy that kept dreams alive and that cloaked the Virtuous Ones from wild animals and enemies during their mystic peregrinations. Inspired by Lumiere’s device and ngHolo beliefs about the cosmic implications of metallurgy, a Virtual nun named Aieda made the spiritual link between metals and mechanics. Along with the somewhat baffled Jesuit, she set about applying the clock’s mechanism to the ngHolo prayer wheels.

Their subsequent machine not only relieved the peasants of the daily chore of spinning the wheels, but it led within decades to a number of inventions, including irrigation pumps, automated pottery wheels, and a programmable loom used to weave the mystical patterns of the ngHolo’s rugs (apparently, they never bothered making more clocks). Aieda believed that the punched cards used to program the looms — an incomplete Italian Tarocco (tarot]) deck still venerated today — allowed the ngHolos to communicate with the “Metal-mind,” the spiritual consciousness that lay asleep in all metals and was awakened through metallurgy.

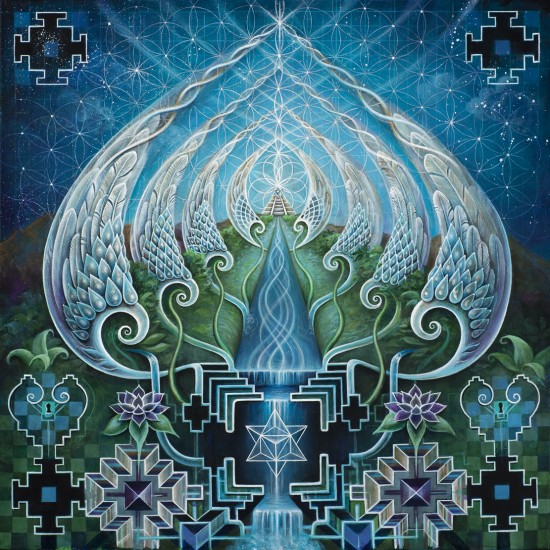

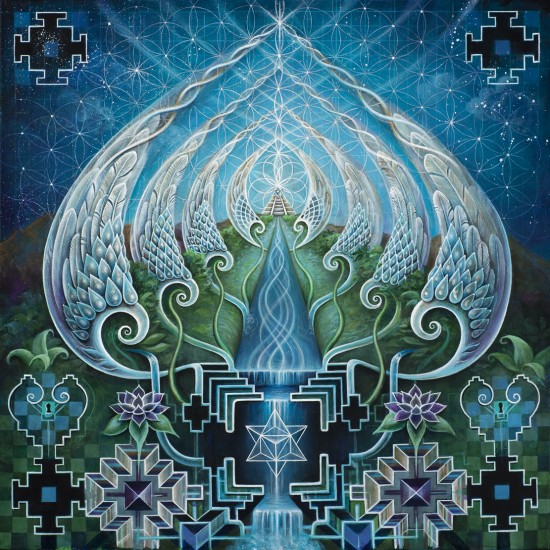

After a yearlong nomadic meditation, during which she never stopped walking, Aieda “received” the knowledge of how to program open-ended and unpredictable combinatory sequences into the mechanical looms. The spontaneous patterns that appeared on subsequent rugs were read as auguries from the Metal-Mind. Despite a tradition of symmetrical mandalic forms, the ngHolo rug patterns Daybreak reproduces from this period show a striking asymmetry, density, and self-similar fractal dimensionality.

Daybreak reports that the ngHolos were mythologically prepared for this development because of one of their quasi-Manichean metallurgic myths. While the four elements familiar to the West — air, earth, fire, and water — were considered to emerge from the earth’s eternally fertile womb, metals were considered the remains of the Alien God’s semen, which had fallen upon earth following a celestial tantric rite. For the ngHolos, metals were not only sacred but contained the potential “seeds” for a powerful galactic consciousness. Through the slow process of metallurgy, these seeds would ripen into Metal-Minds, which were imagined to be (or at least represented iconographically as) colossal grasshopper bodhisattvas. At the end of the world, these beings would shed the material substance of their magical green-grey bodies until only the metallic shine remained. Millions of these ghostly and angular light-bodies of light would then combine into a boundless and collective temple that would draw the Alien God back to earth.

Aieda interpreted the gears of Lumiere’s clock as the grasshopper’s mandibles, and the random patterns from the loom as the first stirrings of the Metal-Mind. Though a few traditionalists labeled her a heretic, Aieda’s work transformed ngHolo spiritual life. The dense patterns emerging from the loom were magically mapped onto the semi-mythic landscape of the Folds, where they formed an immense and lucid matrix of mind known as the “Jewel-Net”. Daybreak calls this net “a symphony of interpenetrating mandalas, an immense and luminous enfolded architecture.” The ngHolos came to believe that the Jewel-Net maintained its coherence through the automated prayer wheels and the psychic intensity generated by the ngHolo’s most dangerous and esoteric rites: equestrian tantra.

Daybreak estimates that by the 18th century, the Virtuous Ones lived an almost entirely psychic existence on the Jewel-Net, their nomadism having shifted from the Karakorum mountains to the more visionary and abstract plateaus of the Folds. For apparently, just as the myth had predicted, the Jewel-Net was growing.

In the Tibetan regions to the South, the Nyingmapas and the shamanic Bon follow the terma tradition, which holds that the sage Padmasambhava hid hundreds of sacred texts in the earth (and the spirit realm), texts that would only be discovered centuries later by tuned-in lamas (the so-called Tibetan Book of the Dead is such a text). Many were encoded in mystical “Dakini” scripts.[2] The ngHolos carried this tradition into the Jewel-Net, where hundreds of thousands of encoded sacred texts were uncovered — or “unfolded” from their visionary plateaus: texts of theology, philosophy, history, iconography, sacred geography. Various spiritual beings co-operated to decode these “treasures.” Using a collective form of the ars memoria, or memory palaces, picked up from Lumiere or another Jesuit,[3] the Virtuals then stored, swapped, and recombined their termas throughout the ever-expanding Jewel-Net.

The overwhelming amount of this information, combined with the ngHolo’s already intense eclecticism, resulted in radical spiritual anarchy. Reflecting the philosophical shift from transcendent renunciation to immanent becoming, the plateaus of the Fold were no longer considered to be “revealed” forms of spiritual reality, but as spaces created “on the wing” out of the infinite potential of the Jewel-Net. Lineages broke down into splinter groups, impartial agnostic “librarians”, iconoclastic magicians, and “anti-monks.” As the Virtuous Ones continued to discover, interpret, and store an increasingly boundless supply of termas, they formed constantly shifting and precarious alliances, frequently struggling with rivals through endless debates or magical “pattern-wars.”

By the time Daybreak arrived, most of these fierce power struggles had relaxed. The following comments, which “unfold” a number of the ngHolo’s countless mnemonic slogans, describe the more balanced philosophy that developed after generations of nomadism in the Jewel-Net. The slogans are in italics, and the text is all Daybreak’s, except for a few of my explanations which appear in brackets. Much of Daybreak’s text remain thoroughly obscure.

Selections

The eye is furrow, seed, and source.

The eye symbolizes attention.

Everything follows from attention, and the awareness of attention is the beginning of awakening: “the cock-crow.” The Jewel-Net pre-exists the eye only as a field of total potential. Attention cuts furrows into this field, preparing the ground for the objects we perceive the seedsto both appear and find a place. But this grid of furrows and seeds, of points and tangents, is not enough to produce “reality” you need the “source,” the energetic of desire or fascination that operates “behind” the eye, to water the seeds. This eye of attention is like a spring which can choose its direction of flow, though over time this spontaneous power is reduced to a habit. But awareness and control begin with this awake gaze, and it should be cultivated.

The Virtuals recognize the inevitability of constantly producing reality, at least as long as one has not achieved “the flight of gnosis.” The plateau grows to fit your shadow is one slogan which Jungians would probably enjoy. But since ngHolo society was evenly divided between agriculture and nomadism, they pictured this reifying tendency in profoundly ambivalent terms. Our habits of perception and action are seen as ruts as much as furrows. In this sense, seeds are materialistic delusions that karmically grow into something larger and more demanding than they initially appear. Sift the seeds, they warn. Some Virtuals interpret Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Eden into the toil of agriculture as a fall into the ruts of perception. The rain that feeds the wild poppy falls from the sky, they say, indicating the “pure production” that is to be aimed for: a spontaneous growth of unpredictable objects generated from the ultimate field of emptiness (the “sky-like mind” of Ch’an).

We ourselves are nothing but seeds grown within furrows dug and watered by the attention of others. Assessing the value of this prepared plot of land that is our “given” world is of primary spiritual importance. The path towards the Jewel-Net comes through preparing our own ground, for the furrows dug by the attention (our patterns of perception) in many way determine the seeds, or objects, that will appear. (Because they farmed on hillsides, ngHolo plots are rarely regular, but follow the various possible folds of the land). So we should carefully prepare the patterns of our attention, its mode of organization, its blend of curves and grids, randomness and order. For the ngHolos, the chaotic woven mandalas that issued from the loom of the Metal-Mind were occult keys to these patterns. But the ngHolos also emphasized the supreme momentum of rootless flight, the nomadic spread of weeds and wild poppies rather than the conscious cultivation of philosophical or material ground. As a famous slogan puts it, I become mushroom, without root, my dharma seeds scattered to the wind.

***

The soul weaves Indra’s net.

Following the anatman doctrines of Buddhism, the Virtuals insist that any fixed notion of self, even the Universal Self, is an illusion. At the same time, the ngHolos emphasize that the self and the world are constantly produced, that the cosmos is both network and void. The allusion here to the Hindu myth of Indra’s web, which the ngHolo’s fused with the image of the universe as pictured in the Avatamsaka Sutra[4]: an infinitely nested and interrelated monadology in which each singularity reflects and embodies a boundless totality.

The Virtuals did not deny the conventional self, but rather filled it with space and emptiness. They call this “weaving the net.” Like a net, the conventional self or ego is something we toss into the infinite potential of reality in order to “catch” our karmic desires, but it too is composed of emptiness[5]. If the net is too thick and tightly-wound, it will retain everything, for there is no void to escape into, and everything will become very heavy and egocentric. If the net is too loose and weakly bound, it will not function larger catches will break its threads, and the smaller will escape.

We never stop weaving the net or trawling the world of potential. Newly woven patterns catch new fish. Of course, the net of the self relates to the larger Jewel-Net. For the ngHolos, the fractal mandalas of the looms were the keys to maintaining the conventional self while weaving them into this larger pattern of multiplicity.

***

The path is a plateau.

For the ngHolos, the notion of a spiritual “path” is a misnomer, for spiritual reality is an endlessly proliferating manifold. The path is a network of paths, a plateau. One can not “follow” a network, but must constantly probe it. Each footprint is a node, which constantly re-produces a number of possible directions. Arrival and departure are fused. As such, immediate and fragmentary spiritual tactics (including these slogans) are prized more than grand strategic methods which attempt to lay out a well-organized hierarchy of stages towards gnosis. Many Virtual Masters achieved fame not for their diligence in pursuing one of the ngHolo’s countless philosophical cults, but for the specific topology of the plateaus they created as they moved through different and frequently antagonistic fields of thought and experience.

***

Webs mar the Jewel-Net.

The Virtuous Ones contrast the image of the suppleness of the open net with the centralized and sticky organization of the web. In a web, the self becomes a spider, a solidified, grasping ego which sits at the center and relates everything to itself. Because a tremendous amount of power over others can be generated through webs, black magicians worshipped the spider of their own egos. The greatest ngHolo necromancers would clandestinely seed patterns in the Jewel Net in order to “catch” the eye of others, adepts who would slowly become bound in an immense pattern they believed to be a new revelation. This “revelation” was actually a web, which would capture the victims in a paranoid spell. Many such victims went mad or become so convinced of having discovered the ultimate pattern that they would be ostracized from the collective. Jewel-Net healers would often attempt to free such individuals by binding them in “devotional webs,” patterns of compassionate paranoia that would “kill the spider.”

***

The flow extinguishes the flame.

An even more aggressive form of magical Jewel-Net combat was the flame. After binding their opponents in a web, vengeful Virtuals would them destroy them with psychic fire. Those victims who were too caught up in the web of their illusory convictions to release themselves would be unable to move, and would either suffer greatly or return the flame. Like the Tibetans, the ngHolos believed that the violent flames were ultimately compassionate, in that they destroyed the unregenerate selfhood. Still, the Virtuals prefer to contrast flames with the flow of water. By flowing, one escapes through the path of least resistance, dissolving the web of selfhood and extinguishing the flame. The flow also becomes the subtlest and most powerful form of counter-attack: the unceasing yet gentle pressure of water eventually erodes the hardest rock[6].

***

The horseman is poised as he flies through the night.

Found on many prayer wheels, saddles and shrines, this slogan contains both an exoteric and esoteric meaning. Esoterically, it refers to a crucial component of the astounding Virtual art of high-speed equestrian tantra. Exoterically, it refers to the quality of balance needed to properly navigate the Jewel-Net: the subtle contrast between the knowledge you accumulate and your beginner’s mind before the new. Given the encyclopedic density of the Net, the Virtuals obviously put great emphasis on the proper gathering, organizing, and storage of termas. But as the masters say, The greater your store, the slower your flight. The greatest Net nomads are as naive as they are wise, know when to jettison information, and avoid the hoarding of knowledge for its own sake. The “web” here also symbolizes the spider-nests that grow around stored or hidden containers. By compassionately sharing this wealth, you unbind yourself from the sticky burdens of knowledge.

***

Answer the Call with a Call

Here the ngHolos alter a crucial element of Manichean soteriology [science of salvation]. For the Manicheans, the couple “Call” and “Answer” are hypostasized [simultaneously considered abstract concepts and mythological beings], and result from the separation of the fragments of cosmic light imprisoned in fallen matter and the Voice of the Alien God who calls these sparks to redemption.[7] The ngHolos mapped this communication system onto the Jewel-Net. Delivering and receiving information, the Virtuals would take on the roles of Call and Answer, foreshadowing the final apocalyptic communication with the Alien God. But the roles would continually change individuals would always Answer the Call with another Call, thus constantly fluctuating between master and student, God and aspirant. Cosmic knowledge was both continually revealed and continually displaced, and the transcendence of the gnostic flash was woven into the phenomenal world of the Jewel-Net. The Folds became an incandescent matrix of communication, a perpetually postponed apocalypse.

***

Crack the dawn!

The Virtuals seek many different modes of gnosis or enlightenment. This slogan refers to one of the foremost of these “horizonless goals:” the gnosis of “staying awake”, or more specifically, always waking up. This is the most exalted yet everyday mode of enlightenment, one which is not attained so much as continually rediscovered. There is only waking up and rubbing your eyes. One of the techniques to developing these moments which we err in considering “states” of consciousness is to allow these very slogans to randomly erupt in the mind. Spontaneously “mad” behavior, tricks, and optical illusions are also common approaches, but the moment they become fixed as “techniques” they begin to lose their efficacy. The point is to cut against established patterns to “kill the Buddha,” as the Ch’an patriarchs say. For example, rather than staring at a beautiful object that catches your eye in the market, observe how others relate to the object.

As in English, ngHolo’s Indo-Chinese dialect contains the image of the dawn as a “crack” or “break.” The peasants believe this crack is real that a day literally ossifies over its 24-hour period, trapping the earth inside a cosmic shell. The shell is then ruptured by the rising sun. But the Virtuals play with this image to emphasize both the violent and nurturing aspects of “always waking up”. On the one hand, perpetual gnosis constantly rends the dreamlike illusion or more exactly, the tentative construction of your present plateau. On the other hand, such gnosis pervades the mind with the empty but pregnant emptiness of the glowing dawn sky.

Some compare perpetual gnosis to a chick breaking through an endless series of nested eggs. While this image of gnosis as a movement through a cosmic collection of Chinese boxes may remind Westerners of the “existential” myth of Sisyphus, the Virtuals saw it as the supreme affirmation of perpetual nomadism. In contrast to Sisyphus, with the heavy burden of his self and his ceaseless linear ascent towards a goal, the Virtuals open up a perpetual field of becoming. Cracking the dawn not only continually grounds the lucidity of gnosis in the present moment, but it also cuts against the mind’s tendency to make gnosis a goal. Even cosmic knowledge must be rent if it becomes a web. The nomad knows that there is no escape, for liberation is achieved only in the act of flight.

Footnotes:

[1] See Hans-Joachim Klimkeit,

Gnosis on the Silk Road (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1993).

[2] See Tulka Thondup Rinpoche, Hidden Teachings of Tibet (London: Wisdom, 1986).

[3] See Frances Yates, The Art of Memory (Chicago; and Jonathan Spence, The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci

[4] Thomas Cleary, trans., The Flower Ornament Scripture: a Translation of The Avatamsaka Sutra (Boston: Shambhala, 1993).

[5] See Lao Tzu, The Way of Life, trans Witter Bynner (New York, 1944) , particularly the eleventh saying: “…The use of clay in moulding pitchers / Comes from the hollow of its absence; / Doors, windows, in a house, / Are used for their emptiness: / Thus we are helped by what is not / To use what is.”

[6] See the I Ching, hexagrams 4 (Youthful Folly) and 29 (the Abysmal).

[7] See Hans Jonas, The Gnostic Religion (Boston: Beacon, 1958), pp.206-238. Note especially the following apocalyptic passage from the Kephalia: “At the end, when the cosmos is dissolved, the…Thought of Life shall gather himself in…His net is his Living Spirit, for with his Spirit he shall catch the Light and the Life that is in all things.”